Chapter 5

Children and adolescents

Principles of prescribing practice in childhood and adolescence1

- Target symptoms, not diagnoses. Diagnosis can be difficult in children and comorbidity is very common. Treatment should target key symptoms. While a working diagnosis is beneficial to frame expectations and help communication with patients and parents, it should be kept in mind that it may take some time for the illness to evolve.

- Technical aspects of paediatric prescribing. The Medicines Act 1968 and European legislation make provision for doctors to use medicines in an 'off-label' or out-oflicence capacity or to use unlicensed medicines. However, individual prescribers are always responsible for ensuring that there is adequate information to support the quality, efficacy, safety and intended use of a drug before prescribing it. It is recognised that the informed use of unlicensed medicines, or of licensed medicines for unlicensed applications, ('off-label' use) is often necessary in paediatric practice.

- Prescription writing: inclusion of age is a legal requirement in the case of prescription-only medicines for children under 12 years of age, but it is preferable to state the age for all prescriptions for children.

- Begin with less, go slow and be prepared to end with more. In out-patient care, dosage will usually commence lower in mg/kg per day terms than adults and finish higher in mg/kg per day terms, if titrated to a point of maximal response.

- Multiple medications are often required in the severely ill. Monotherapy is ideal. However, childhood-onset illness can be severe and may require treatment with psychosocial approaches in combination with more than one medication.2

- Allow time for an adequate trial of treatment. Children are generally more ill than their adult counterparts and will often require longer periods of treatment before responding. An adequate trial of treatment for those who have required in-patient care may well take 8 weeks for depression or schizophrenia.

- Where possible, change one drug at a time.

- Monitor outcome in more than one setting. For symptomatic treatments (such as stimulants for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]), bear in mind that the expression of problems may be different across settings (e.g. home and school); a dose titrated against parent reports may be too high for the daytime at school

- Patient and family medication education is essential. For some child and adolescent psychiatric patients the need for medication will be life-long. The first experiences with medications are therefore crucial to long-term outcomes and adherence.

References

- Nunn K, Dey C. The Clinician's Guide to Psychotropic Prescribing in Children and Adolescents. Sydney: Glade Publishing; 2003.

- Luk E, Reed E. Polypharmacy or Pharmacologically Rich? In: Nunn KP, Dey C, eds. The Clinician's Guide to Psychotropic Prescribing in Children and Adolescents, 2nd edn. Sydney: Glade Publishing; 2003, pp. 8–11.

Further reading

For detailed adverse effects of CNS drugs in children and adolescents, see:

Paediatric Formulary Committee. BNF for Children 2013–2014. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2013.

Martin A, Scahill L, Charney DS, Leckman JF. Pediatric Psychopharmacology: Principles and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Riddle MA et al. Introduction: Issues and viewpoints in pediatric psychopharmacology. Int Rev Psychiatry 2008; 20:119–120.

Depression in children and adolescents

Psychological intervention

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines1 recommend that psychological intervention should be considered as the first-line treatment for child and adolescent depression. Psycho-educational programmes, non-directive supportive therapy, group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and self-help are indicated for mild-to-moderate depression. More specific and intensive psychological interventions including CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy and short-term family therapy are recommended for moderate-to-severe depression.1 The NICE guideline recommends the introduction of medication in conjunction with psychological treatments if there is failure to respond to psychological treatment.1 In the light of changing evidence this advice has recently been questioned with recommendations for the use of medication at a much earlier stage of treatment in cases of moderate-to-severe depression.2

Pharmacotherapy

The NICE guideline CG281 supports the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) but only in combination with psychological forms of therapy. Two US studies, Treatment of Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS)3 and Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescence (TORDIA)4 found that CBT confers benefit when used in combination with medication. A large UK study did not establish the benefits of combined therapy (fluoxetine plus CBT) and demonstrated that the use of fluoxetine on its own in addition to routine clinical care is effective in treating moderate-to-severe depression.5,6 Whether CBT provides added value to treatment and outcomes remains a controversial area, but in view of the recent research it is recommended that medication is started at a much earlier stage in treatment, especially if the depression is severe.2 Evidence7 now supports the administration of fluoxetine for moderate-to-severe depression sooner than the 12 weeks currently recommended in the original NICE guideline.2 The NICE Surveillance Group also suggests that the additional benefit of combining CBT and antidepressant treatment compared with the administration of antidepressants alone may not be as significant as previously thought.2

The more severe the depressive episode the more likely it is that medication, in combination with psychological treatment or on its own, will be efficacious in the early stages of treatment.8,9 Good initial response is a sign of improved rates of recovery and outcomes.3,4

Fluoxetine is the first-line pharmacological treatment.10 In the UK it is licensed for use for children and young people from 8–18 to treat moderate-to-severe major depression which is unresponsive to psychological therapy after 4–6 sessions. It is recommended that pharmacotherapy should be administered in combination with a concurrent psychological therapy.1,10–13 Cochrane agree that fluoxetine is the drug of choice in this patient group.8 A recent multiple-treatments meta-analysis14 confirmed fluoxetine's superiority over CBT and other drugs, but concluded that sertraline and mirtazapine might offer the optimal balance of efficacy and tolerability.

Fluoxetine and escitalopram are the only antidepressants approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adolescents and fluoxetine is the only FDAapproved medication for pre-pubertal children. Generally speaking, adolescents can be expected to respond better to antidepressants than younger children, particularly those under the age of 12.15

Studies in adults have shown that the elimination half-life of fluoxetine is 1–4 days and 7–15 days for its primary metabolite, norfluoxetine, making it a preferable SSRI for adolescents who are less likely to experience withdrawal effects when omitting a dose or stopping the medication abruptly.16,17 Body weight influences fluoxetine concentrations and starting doses of medication have to be lowered in children. However, during treatment the half-lives of most antidepressants are much lower in children than in adolescents and higher doses may have to be administered in order to achieve adequate blood concentration and therapeutic effects.15,17

Fluoxetine should be started at a low dose of 10 mg daily1 and increased weekly until a minimum effective dosage of 20 mg daily is achieved.15 Patients and their parents/carers should be informed about the potential side-effects associated with SSRI treatment and know how to seek help in an emergency. Any pre-existing symptoms that might be interpreted as side-effects (e.g. agitation, anxiety, suicidality) should be noted.

Alternative SSRIs and other antidepressants

If there is no response to fluoxetine and pharmacotherapy is still considered to be the most favourable option, an alternative SSRI such as sertraline and citalopram1 may be used cautiously by specialists. Evidence suggests some efficacy for sertraline1,18,19 but one randomised controlled trial (RCT) showed it to be inferior to CBT.20 Citalopram, also recommended by NICE,1 may be less effective10,21,22 and is probably more toxic in overdose.23

Escitalopram is the therapeutically active isomer of racemic citalopram.24 It has been shown to be efficacious in two RCTs25,26 and is approved by the FDA for use in 12–18 year olds.

Sertraline, citalopram and escitalopram are quickly metabolised by children and twice daily dosing should be considered.27,28 Sertraline, citalopram and escitalopram should also be started at low doses and titrated weekly up to minimum effective doses; sertraline 50–100 mg; citalopram 20 mg and escitalopram 10 mg.29

Paroxetine is considered to be an unsuitable option.1,10

The placebo response rate is high in young people with depression.8,29 On average drug and placebo response rates in children and adolescents differ by only 10%12 and the benefits of active treatment are likely to be modest. It is estimated that 1 in 6–10 may benefit from the active treatment (although 60% or more show improvement).1,12,30 There is some evidence to suggest dose increases can improve response.31

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are not effective in pre-pubertal children but may have marginal efficacy in adolescents.12,32 Amitriptyline (up to 200 mg/day), imipramine (up to 300 mg/day) and nortriptyline have all been studied in RCTs. Note that due to more extensive metabolism, young people require higher mg/kg doses than adults. The side-effect burden associated with TCAs is considerable. Vertigo, orthostatic hypotension, tremor and dry mouth limit tolerability.32 Tricyclics are also more cardiotoxic in young people than in adults. Baseline and on-treatment electrocardiograms (ECGs) should be performed. Co-prescribing with other drugs known to prolong the QTc interval should be avoided. There is no evidence that adolescents who fail to respond to SSRIs will respond to tricyclics.

There is little evidence for the use of mirtazapine33 but it is sometimes used in clinical practice where sleep is a problem.

Omega-3 fatty acids may be effective in childhood depression but evidence is minimal.34

St John's wort should be avoided because of the risk of interaction (see Chapter 7).

Severe depression that is life-threatening or unresponsive to other treatments may respond to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).35 ECT should not be used in children under 12.1 The effects of ECT on the developing brain are unknown.

Safety of antidepressants

When prescribing SSRIs it is important that the dose is increased slowly to minimise the risk of treatment-emergent agitation and that patients are monitored closely for the development of treatment-emergent suicidal thoughts and acts. Patients should be seen at least weekly in the early stages of treatment. Side-effects linked to SSRIs include sedation, insomnia and gastrointestinal symptoms and, rarely, can induce bleeding, serotonin syndrome, activation and mania. More detailed reviews of these problems in adults can be found in Chapter 4.

There is evidence from meta-analyses of pooled trials that antidepressants increase the risk of suicidal behaviours in the short term although no completed suicides were reported in any of the trials.3,30,36–42 The risk of spontaneously reported suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour in adolescents treated with antidepressant medication is 1–3 out of every 100 children.41 Conversely, some studies point to the risk of suicide associated with untreated depression.43 Reduced prescribing of SSRIs in the USA44 and The Netherlands45 has been linked to an increase in the rate of suicide.

The TADS study, which compared CBT with fluoxetine, placebo and combined CBT and fluoxetine, showed that all treatment arms were effective in reducing suicidal ideation, but that the combined treatment of fluoxetine and CBT reduced the risk of suicidal events to the greatest extent.3 Overall, the potential benefits of treatment with antidepressants outweigh the risks in relation to suicidal behaviours.

Starting and titrating the dose of SSRIs and alternative medication

The administration of all SSRIs should be monitored against the emergence of sideeffects and the dose should be reduced if side-effects persist beyond one week. In this case the dose of the medication should be lowered to the highest tolerable dose. SSRI medication should be administered for a minimum of 4–6 weeks and if the child or young person fails to respond and remains symptomatic a dose increase should be considered. A switch to another medication should be made if there is insufficient improvement after approximately 10–12 weeks (switch earlier if there are no signs of improvement). Medication effectiveness should be initially monitored at weekly intervals and its effectiveness re-evaluated every 4–6 weeks.28

Duration of treatment and discontinuation of SSRIs

There is little evidence regarding optimum duration of treatment.46 Adding CBT to fluoxetine during continuation treatment has shown sustained remission and lower rates of relapse in comparison to medication on its own.47 To consolidate the response to the acute treatment and avoid relapse, treatment with fluoxetine should continue for at least 6 months and up to 12 months.48,49 There is a significant reduction of the risk of relapse with a continuation of treatment for 6 months.28,48

At the end of treatment, the antidepressant dose should be tapered slowly to minimise discontinuation symptoms. Ideally this should be done over 6–12 weeks.1,28 Because of fluoxetine's long duration of action it can probably be safely tapered over 2 weeks.

Refractory depression

There are no clear clinical guidelines for the management of treatment-resistant depression in adolescents1,50 but there is evidence from the TORDIA published studies4 that adolescents who failed to respond to treatment with one SSRI may improve when switched to another SSRI or venlafaxine when the pharmacotherapy was combined with concurrent CBT. A switch to an SSRI was just as efficacious as a switch to venlafaxine with less severe side-effects. Recent TORDIA results demonstrate that with continued treatment of depression among treatment-resistant adolescents approximately one third remit.51 However, the venlafaxine group had more side-effects and there was an association with higher rates of suicidal events in those who entered the study with high suicidal ideation. Venlafaxine should be used with caution and under specialist guidance.1,4,52 Note that a recent large study suggested no increased risk of suicidality for venlafaxine.53

Augmentation with a second medication has not been studied in RCTs in depressed children and adolescents who have either not responded to treatment or have only shown a partial improvement. Case studies and post hoc TORDIA studies have demonstrated some benefits from the addition of antipsychotics.54–56

Risk of bipolar disorder

Some young people, and especially children, will develop behavioural activation in response to the administration of SSRIs. It is estimated that 3–8% of young people prescribed SSRIs present with heightened mood, restlessness and silliness which is transitory in nature. This disinhibitory response to starting SSRI medication or being prescribed increasing doses of medication needs to be differentiated from hypomania or mania.57 Early bipolar illness should be suspected when the presentation is one of severe depression, associated with psychosis or rapid mood shifts and the condition worsens on treatment with antidepressants. Early studies suggested that between 20% and 40% of children and young people presenting with depression will develop bipolar affective disorder (BAD)58 when treated with antidepressants (the antidepressants acting so as to reveal the disorder, not cause it). In some studies in bipolar patients treatment with antidepressants is associated with new or worsening rapid cycling in as many as 23% of patients.59 It seems that the younger the child, the greater the risk.60 In the case of emergent mania early treatment with atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilisers should be considered.61 More recently it has been advocated that cautiously administered SSRIs should not be withheld in cases of severe depression and BAD.62 There is limited evidence from open label studies that lamotrigine is effective in treating depression in the context of BAD.63,64 There is evidence from TORDIA that sub-syndromal manic symptoms at baseline and over time are predictors of poor outcome in adolescent depression.65 Adult studies suggest that olanzapine, quetiapine and lurasidone are superior to antidepressants in bipolar depression (see Chapter 3).

|

Box 5.1 Summary of treatment of depression in children and adolescents

|

|

First line

Second line

Third line

Fourth line

|

Fluoxetine + CBT

Escitalopram + CBT

Sertraline, citalopram (more toxic in overdose)

Venlafaxine (less well tolerated)

Mirtazapine (where sedation required)

Consider adding quetiapine/aripiprazole to SSRI treatment

|

|

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression in children and young people: identification and management in primary, community and secondary care. Clinical Guideline 28, 2005. http://www.nice.org.uk

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in children and young people: review decision - Oct 13. Clinical Guideline 28, 2013. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG28/ReviewDecision/pdf/English

- The TADS Team. The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64:1132–1143.

- Brent D et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: The TORDIA Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2008; 299:901–913.

- Goodyer I et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and routine specialist care with and without cognitive behaviour therapy in adolescents with major depression: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007; 335:142.

- Dubicka B, March J, Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Vitiello B, Goodyer I. The treatment of adolescent major depression: A comparison of the ADAPT and TADS trials. In: Yule W, ed. Depression in Childhood and Adolescence: The Way Forward. London: Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health; 2009.

- Dubicka B et al. Combined treatment with cognitive-behavioural therapy in adolescent depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 197:433–440.

- Hetrick SE et al. Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 11:CD004851.

- March J et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 292:807–820.

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents including a summary of available safety and efficacy data. London: MHRA; 2005. http://www.mhra.gov.uk

- Kratochvil CJ et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pediatric depression: is the balance between benefits and risks favorable? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006; 16:11–24.

- Tsapakis EM et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in juvenile depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 193:10–17.

- Whittington CJ et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004; 363:1341–1345.

- Ma D et al. Comparative efficacy, acceptability, and safety of medicinal, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and placebo treatments for acute major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin 2014.

- Sakolsky DJ et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011; 31:92–97.

- Wilens TE et al. Fluoxetine pharmacokinetics in pediatric patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 22:568–575.

- Findling RL et al. The relevance of pharmacokinetic studies in designing efficacy trials in juvenile major depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006; 16:131–145.

- Donnelly CL et al. Sertraline in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:1162–1170.

- Rynn M et al. Long-term sertraline treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006; 16:103–116.

- Melvin GA et al. A comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy, sertraline, and their combination for adolescent depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:1151–1161.

- Wagner KD et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of citalopram for the treatment of major depression in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1079–1083.

- von Knorring AL et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of citalopram in adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26:311–315.

- Klein-Schwartz W et al. Comparison of citalopram and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor ingestions in children. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2012; 50:418–423.

- Hyttel J et al. The pharmacological effect of citalopram residues in the (S)-(+)-enantiomer. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 1992; 88:157–160.

- Wagner KD et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram in the treatment of pediatric depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:280–288.

- Emslie GJ et al. Escitalopram in the treatment of adolescent depression: a randomized placebo-controlled multisite trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:721–729.

- Axelson DA et al. Sertraline pharmacokinetics and dynamics in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:1037–1044.

- Sakolsky D et al. Developmentally informed pharmacotherapy for child and adolescent depressive disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2012; 21:313–25, viii.

- Jureidini JN et al. Efficacy and safety of antidepressants for children and adolescents. BMJ 2004; 328:879–883.

- Bridge JA et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2007; 297:1683–1696.

- Heiligenstein JH et al. Fluoxetine 40-60 mg versus fluoxetine 20 mg in the treatment of children and adolescents with a less-than-complete response to nine-week treatment with fluoxetine 10-20 mg: a pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006; 16:207–217.

- Hazell P et al. Tricyclic drugs for depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6:CD002317.

- Haapasalo-Pesu KM et al. Mirtazapine in the treatment of adolescents with major depression: an open-label, multicenter pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004; 14:175–184.

- Nemets H et al. Omega-3 treatment of childhood depression: a controlled, double-blind pilot study. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1098–1100.

- McKeough G. Electroconvulsive therapy. In: Nunn KP, Dey C, eds. The Clinician's Guide to Psychotropic Prescribing in Children and Adolescents. Sydney: Glade Publishing; 2003, pp. 358–365.

- Martinez C et al. Antidepressant treatment and the risk of fatal and non-fatal self harm in first episode depression: nested case-control study. BMJ 2005; 330:389.

- Kaizar EE et al. Do antidepressants cause suicidality in children? A Bayesian meta-analysis. Clin Trials 2006; 3:73–90.

- Mosholder AD et al. Suicidal adverse events in pediatric randomized, controlled clinical trials of antidepressant drugs are associated with active drug treatment: a meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006; 16:25–32.

- Simon GE et al. Suicide risk during antidepressant treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:41–47.

- Olfson M et al. Antidepressant drug therapy and suicide in severely depressed children and adults: A case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:865–872.

- Hammad TA et al. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:332–339.

- Dubicka B et al. Suicidal behaviour in youths with depression treated with new-generation antidepressants: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2006; 189:393–398.

- Gibbons RD et al. Relationship between antidepressants and suicide attempts: an analysis of the Veterans Health Administration data sets. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1044–1049.

- Libby AM et al. Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:884–891.

- Gibbons RD et al. Early evidence on the effects of regulators' suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1356–1363.

- Kennard BD et al. Relapse and recurrence in pediatric depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2006; 15:1057–79, xi.

- Kennard BD et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy to prevent relapse in pediatric responders to pharmacotherapy for major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008; 47:1395–1404.

- Emslie GJ et al. Fluoxetine treatment for prevention of relapse of depression in children and adolescents: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43:1397–1405.

- Emslie GJ et al. Fluoxetine versus placebo in preventing relapse of major depression in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:459–467.

- Birmaher B et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46:1503–1526.

- Emslie GJ et al. Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA): week 24 outcomes. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167:782–791.

- Brent DA et al. Predictors of spontaneous and systematically assessed suicidal adverse events in the treatment of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:418–426.

- Cooper WO et al. Antidepressants and suicide attempts in children. Pediatrics 2014; 133:204–210.

- Vitiello B et al. Long-term outcome of adolescent depression initially resistant to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment: a follow-up study of the TORDIA sample. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72:388–396.

- Pathak S et al. Adjunctive quetiapine for treatment-resistant adolescent major depressive disorder: a case series. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005; 15:696–702.

- Wagner KD et al. Out of the black box: treatment of resistant depression in adolescents and the antidepressant controversy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2012; 22:5–10.

- Wilens TE et al. Disentangling disinhibition. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:1225–1227.

- Geller B et al. Rate and predictors of prepubertal bipolarity during follow-up of 6- to 12-year-old depressed children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:461–468.

- Ghaemi SN et al. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:804–808.

- Martin A et al. Age effects on antidepressant-induced manic conversion. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004; 158:773–780.

- Dubicka B et al. Pharmacological treatment of depression and bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2010; 16:402–412.

- Joseph MF et al. Antidepressant-coincident mania in children and adolescents treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Future Neurol 2009; 4:87–102.

- Chang K et al. An open-label study of lamotrigine adjunct or monotherapy for the treatment of adolescents with bipolar depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:298–304.

- Pavuluri MN et al. Effectiveness of lamotrigine in maintaining symptom control in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2009; 19:75–82.

- Maalouf FT et al. Do sub-syndromal manic symptoms influence outcome in treatment resistant depression in adolescents? A latent class analysis from the TORDIA study. J Affect Disord 2012; 138:86––95.

Bipolar illness in children and adolescents

Diagnostic issues

Bipolar affective disorder (BAD) in children has become an area of intense research interest and controversy in recent years.1,2 While classical manic presentations fulfilling DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria are well known to clinicians treating adolescents, they are rare in younger children.3,4 Claims that mania in pre-puberty may present as chronic (non-episodic) irritability or with extremely short (few hours) episodes should be treated with great caution.2 Short-lived episodes of exuberance are normative in children, while temper outbursts and mood lability can present in children with a wide range of other primary diagnoses (such as conduct, anxiety, depressive, and autism spectrum disorders).5 A detailed developmental assessment should therefore be the basis of any treatment decisions.

Clinical guidance

Before prescribing

- Establish a clinical diagnosis informed by a structured instrument assessment if possible. Try to monitor symptom patterns prospectively with mood or sleep diaries. If in doubt, seek specialist advice early on.

- Explain the diagnosis to the patient and family and invest time and effort in psychoeducation. This is likely to improve adherence and there is evidence that it reduces relapse rates at least in adults.6

- Measure baseline symptoms of mania (e.g. Young Mania Rating Scale7[YMRS]), depression (e.g. Children's Depression Rating Scale8[CDRS]), and impairment (e.g. Clinical Global Impression - BAD version9). Use these to set a clear and realistic treatment goal.

- Measure baseline height, weight, blood pressure and baseline bloods (including fasting glucose, lipids and prolactin levels).

What to prescribe

- Either second-generation antipsychotics (SGA) or mood stabilisers (MS) may be used as first-line treatment for youth with BAD, according to existing guidelines.10,11 Most of the evidence is for the treatment of acute episodes.

- SGAs seem to show greater short-term efficacy (effect size (ES) = 0.65 compared with placebo) than MS (ES = 0.20 compared with placebo) in youth, according to a recent meta-analysis.12

- SGA seem to produce significantly greater weight gain and somnolence in youth compared with adults.12

- Polycystic ovary syndrome and associated infertility are particular concerns when valproate is used in adolescent girls and NICE11 recommends avoiding its use in women of child-bearing age. Beware of teratogenicity.

- Adherence to lithium and blood-level testing may be difficult in adolescents. Beware of teratogenicity.

- Combinations of SGAs with MS are common but NICE guidelines11 should be noted.

- Overall, we recommend the use of SGAs as first line for the acute treatment of mania in children and adolescents (see Table 5.1, Table 5.2, Table 5.3), similar to recommendations in adults.

After prescribing

- Assess and measure symptoms on a regular basis to establish effectiveness.

- Monitor weight and height at each visit and repeat bloods at 3 months (then every 6 months). Offer advice on healthy lifestyle and exercise.

- The duration of most medication trials is between 3–5 weeks. This should guide decisions about how long to try a single drug in a patient. A complete absence of response at 1–2 weeks should prompt a switch to another SGA.

- If non-response, check compliance, measure levels (where possible), and consider increasing dose. Consider concurrent use of SGA and MS.

- Judicious extrapolation of the evidence from adults13 is required because of the very limited evidence base in youth with BAD. This includes treatment duration and prophylaxis.11,12

- We recommend that a successful acute treatment of a mood episode should be continued as long-term prophylaxis.

Specific issues

- Bipolar depression is a common clinical challenge, the treatment of which has been understudied in youth. In adults, there is considerably better evidence about efficacious treatments (see section on 'Bipolar depression' in Chapter 3), such as quetiapine;14,15 surprisingly, however, a small study in 32 adolescents,16 followed by a larger RCT17 (n = 193) failed to show effectiveness. This study had a high placebo response and this will need to be reviewed once the data have been published in an academic journal. Lurasidone was recently shown to be effective in bipolar depression in adults18 with a benign metabolic profile, which makes it a good candidate for trials in youth. Note that lamotrigine has only modest, if any, effects in adult bipolar depression;19 it has not been studied in RCTs in children and adolescents and is, therefore, not recommended. Antidepressants should be used with care and only in presence of an antimanic agent.11 There is very little evidence for the benefit of antidepressants in bipolar depression in adults.20 Due to the dearth of trials in youth, we would recommend careful extrapolation from adult studies and use of quetiapine in older adolescents as first-line treatment.

- The exact relationship between ADHD and BAD is still debated. Some evidence suggests that stimulants in children with ADHD and manic symptoms may be well tolerated21 and that they may be safe and effective to use after mood stabilisation.21 Caution and experience with prescribing these drugs are required.

Table 5.1 Summary of RCT evidence on medication used in youth with bipolar mania

|

Medication

|

Comment

|

|

Lithium

|

One double-blind placebo-controlled randomised trial23 showed significant reductions in substance use and clinical ratings after 6 weeks, in 25 adolescents with BAD and co-morbid substance abuse. In a double blind placebo-controlled discontinuation trial (n = 40) over 2 weeks, no significant difference in relapse rates were found between lithium and placebo24

Lithium and divalproex did not differ in an 18-months maintenance trial in youths (n = 60) who initially stabilised on combination pharmacotherapy of lithium and divalproex25

|

|

Valproate

|

In an RCT (n = 150)26 divalproex ER (titrated to clinical response or 80-125 mg/L) did not lead to significant differences in mean YMRS compared with placebo at 4 weeks

|

|

Oxcarbazepine

|

A double-blind placebo-controlled study (n = 116) did not show significant differences between placebo and oxcarbazepine (mean dose 15 mg/day) in reducing mania rating at 7 weeks27

|

|

Olanzapine

|

A double blind, placebo-controlled study (n = 161)28 showed olanzapine (5-20 mg/day) to be significantly more effective than placebo in YMRS mean score reduction over a period of 3 weeks. Note the higher weight gain in the treatment group (weight gain was 3.7 kg for olanzapine versus 0.3 kg for placebo) and the associated significantly increased fasting glucose, total cholesterol, AST, ALT, and uric acid

|

|

Risperidone

|

A double blind, placebo-controlled study (n = 169) showed risperidone (at doses 0.5-2.5 or 3-6 mg) to be significantly more effective than placebo in YMRS mean score reduction in a 3-week follow up.29 The lower dose seems to lead to same benefits at a lower risk of side-effects. Sleepiness and fatigue common in the treatment arms. Note, mean weight increase in treatment groups (0.7 kg versus 1.7 kg for the low and 1.4 kg for the high dose arm)

In the Treatment of Early Age Mania (TEAM) study, higher response rates (and metabolic side-effects) occurred with risperidone (mean dose of 2.57 mg) versus lithium (mean level of 1.09 mmol/L) and divalproex sodium (mean level of 113.6 mg/L).30 However, the results need to be interpreted with caution as the definition of mania was broad

|

|

Quetiapine

|

A double blind, placebo-controlled study (n = 277)31 showed quetiapine (at doses of 400 mg/day or 600 mg/day) to be significantly better than placebo in reducing mean YMRS scores at 3 weeks. The most common side-effects included somnolence and sedation. Weight gain was 1.7 kg in the quetiapine group versus 0.4 kg for placebo

Quetiapine is effective as an adjunct to valproate compared with valproate alone (n = 30, 6 weeks)32 and was equally effective as valproate in a double blind trial (n = 50, 4 weeks)33

|

|

Aripiprazole

|

A double blind placebo controlled study34,35 showed aripiprazole (at doses 10 mg/day or 30 mg/day) to be significantly better than placebo in reducing mean YMRS scores at both 4 weeks (n = 296)34 and 30 weeks (n = 210)35. Note, the significantly higher incidence of extrapyramidal side-effects in the treatment groups (especially the higher dose). Weight gain was significantly higher in the treatment groups compared to placebo (3.0 kg versus 6.5 kg for the low and 6.6 kg for the high dose arm) at week 30 but not at week 4

|

|

Ziprasidone

|

A double blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 237)36 showed ziprasidone (at flexible doses 40-160 mg) to be significantly more effective than placebo in reducing mean YMRS scores at 4 weeks. Sedation and somnolence were the most common side-effects, while it demonstrated a neutral metabolic profile and no QTc prolongation

Ziprasidone is not marketed in the UK and some other countries

|

|

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BAD, bipolar affective disorder; ER, extended release; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; RCT, randomised controlled trial; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

|

Table 5.2 Recommended first-line treatments for acute mania*

|

Drug

|

Dose

|

|

Aripiprazole

|

10 mg daily

|

|

Olanzapine

|

5-20 mg daily

|

|

Quetiapine

|

Up to 400 mg daily

|

|

Risperidone

|

0.5-2.5 mg daily

|

|

*Continue acutely effective dosing regimen as prophylaxis.

|

Table 5.3 Recommended first-line treatments for bipolar depression*

|

Drug

|

Dose

|

|

Lurasidone

|

18.5-111 (20-120) mg daily

|

|

Olanzapine

|

5-2 0 mg daily

|

|

Quetiapine

|

Up to 300 mg daily

|

|

*Continue acutely effective dosing regimen as prophylaxis.

|

- The DSM-5 has introduced the new category of Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD) to capture severely irritable children (who were commonly misdiagnosed as having BAD in parts of the USA). There is no established treatment for DMDD yet. Lithium is ineffective,22 but SSRIs and psychological treatment options may be considered.5

Other treatments

There is evidence for adults and children that adjunct treatments including psychoeducation, CBT and especially family-focused interventions, can enhance treatment and reduce depression relapse rates in bipolar disorder.13

References

- Carlson GA et al. Phenomenology and diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: complexities and developmental issues. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18:939–969.

- Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168:129–142.

- Costello EJ et al. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth. Goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1129–1136.

- Stringaris A et al. Youth meeting symptom and impairment criteria for mania-like episodes lasting less than four days: an epidemiological enquiry. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010; 51:31–38.

- Krieger FV et al. Bipolar disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation in children and adolescents: assessment, diagnosis and treatment. Evid Based Ment Health 2013; 16:93–94.

- Colom F et al. A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:402–407.

- Young RC et al. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429–435.

- Poznanski EO et al. Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the children's depression rating scale. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1984; 23:191–197.

- Spearing MK et al. Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): the CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res 1997; 73:159–171.

- Kowatch RA et al. Treatment guidelines for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:213–235.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder. The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. Clinical Guideline 38, 2006. http://www.nice.org.uk

- Correll CU et al. Antipsychotic and mood stabilizer efficacy and tolerability in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar I mania: a comparative analysis of acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 2010; 12:116–141.

- Geddes JR et al. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet 2013; 381:1672–1682.

- Calabrese JR et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1351–1360.

- Thase ME et al. Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar I and II depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (the BOLDER II study). J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26:600–609.

- Delbello MP et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of quetiapine for depressed adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2009; 11:483–493.

- AstraZeneca. An 8-week, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of quetiapine fumarate (SEROQUEL) extended-release in children and adolescent subjects with bipolar depression (Clinical Trial NCT00811473), 2012. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT00811473

- Loebel A et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171:160–168.

- Calabrese JR et al. Lamotrigine in the acute treatment of bipolar depression: results of five double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Bipolar Disord 2008; 10:323–333.

- Pacchiarotti I et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2013; 170:1249–1262.

- Goldsmith M et al. Antidepressants and psychostimulants in pediatric populations: is there an association with mania? Paediatr Drugs 2011; 13:225–243.

- Dickstein DP et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of lithium in youths with severe mood dysregulation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2009; 19:61–73.

- Geller B et al. Double-blind and placebo-controlled study of lithium for adolescent bipolar disorders with secondary substance dependency. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:171–178.

- Kafantaris V et al. Lithium treatment of acute mania in adolescents: a placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43:984–993.

- Findling RL et al. Double-blind 18-month trial of lithium versus divalproex maintenance treatment in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:409–417.

- Wagner KD et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of divalproex extended-release in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:519–532.

- Wagner KD et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxcarbazepine in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1179–1186.

- Tohen M et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of adolescents with bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1547–1556.

- Haas M et al. Risperidone for the treatment of acute mania in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Bipolar Disord 2009; 11:687–700.

- Geller B et al. A randomized controlled trial of risperidone, lithium, or divalproex sodium for initial treatment of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed phase, in children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69:515–528.

- Pathak S et al. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in children and adolescents with mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a 3-week, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74:e100–e109.

- Delbello MP et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:1216–1223.

- Delbello MP et al. A double-blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:305–313.

- Findling RL et al. Acute treatment of pediatric bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episode, with aripiprazole: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:1441–1451.

- Findling RL et al. Aripiprazole for the treatment of pediatric bipolar I disorder: a 30-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15:138–149.

- Findling RL et al. Ziprasidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: results from a placebo-controlled efficacy and long-term open-extension study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2013; 23:531–544.

Psychosis in children and adolescents

Schizophrenia is rare in children but the incidence increases rapidly in adolescence. Early-onset schizophrenia-spectrum (EOSS) disorder is often chronic and in the majority of cases requires long-term treatment with antipsychotic medication.1

There have been three major RCTs of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs), all of them showing high rates of extrapyramidal side-effects (EPSs) and significant sedation.1 Treatment-emergent dyskinesias can also be problematic.2 First-generation antipsychotics should generally be avoided in children.

There have been a number of randomised controlled trials of second-generation antipsychotics in EOSS disorder.3–8 Olanzapine, risperidone and aripiprazole have all been shown to be effective in the treatment of psychosis but there is no information to support the superiority of any one agent over another. There is also some evidence from uncontrolled trials for quetiapine9–11 and for ziprasidone,12 but concerns have been raised about the safety of ziprasidone.13,14

Children and adolescents are at greater risk than adults for side-effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, raised prolactin, sedation, weight gain and metabolic effects.15

There is evidence that clozapine is effective in treatment-resistant psychosis in adolescents, although this population may be more prone to neutropenia and seizures than adults.16–18

Overall, algorithms for treating psychosis in young people are the same as those for adult patients (see Chapter 2). NICE19 recommends oral antipsychotics in conjunction with family interventions and individual CBT. Doses should be at the lower end of the adult range if licensed for children and adolescents; below the lower range if not. See Box 5.2.

Box 5.2 Summary of drug treatment of psychosis in children and adolescents

|

Box 5.2 Summary of drug treatment of psychosis in children and adolescents

|

|

First choice

|

Allow patient to choose from:

aripiprazole (to 10 mg),

olanzapine (to 10 mg)

risperidone (to 3 mg)

|

|

Second choice

|

Switch to alternative from list above*

|

|

Third choice

|

Clozapine

|

|

* Based on data obtained from the treatment of younger adults, olanzapine should be tried before moving to clozapine.20

|

|

References

- Kumra S et al. Efficacy and tolerability of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2008; 34:60–71.

- Connor DF et al. Neuroleptic-related dyskinesias in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:967–974.

- Sikich L et al. A pilot study of risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol in psychotic youth: a double-blind, randomized, 8-week trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29:133–145.

- Findling RL et al. A multiple-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral aripiprazole for treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:1432–1441.

- Haas M et al. A 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2009; 19:611–621.

- Haas M et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of two dosing regimens in adolescent schizophrenia: double-blind study. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 194:158–164.

- Sikich L et al. Double-blind comparison of firstand second-generation antipsychotics in early-onset schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS) study. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:1420–1431.

- Kryzhanovskaya L et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in adolescents with schizophrenia: a 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:60–70.

- McConville B et al. Long-term safety, tolerability, and clinical efficacy of quetiapine in adolescents: an open-label extension trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003; 13:75–82.

- Schimmelmann BG et al. A prospective 12-week study of quetiapine in adolescents with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2007; 17:768–778.

- McConville BJ et al. Pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and clinical effectiveness of quetiapine fumarate: an open-label trial in adolescents with psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:252–260.

- Patel NC et al. Experience with ziprasidone. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:495.

- Scahill L et al. Sudden death in a patient with Tourette syndrome during a clinical trial of ziprasidone. J Psychopharmacol 2005; 19:205–206.

- Blair J et al. Electrocardiographic changes in children and adolescents treated with ziprasidone: a prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:73–79.

- Correll CU. Addressing adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment in young patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72:e01.

- Kumra S et al. Childhood-onset schizophrenia. A double-blind clozapine-haloperidol comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1090–1097.

- Shaw P et al. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: A double-blind, randomized clozapine-olanzapine comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:721–730.

- Kumra S et al. Clozapine and "high-dose" olanzapine in refractory early-onset schizophrenia: a 12-week randomized and double-blind comparison. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 63:524–529.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: Recognition and management. Clinical Guideline 155, 2013. http://www.nice.org/

- Agid O et al. An algorithm-based approach to first-episode schizophrenia: response rates over 3 prospective antipsychotic trials with a retrospective data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72:1439–1444.

Further reading

Masi G et al. Management of schizophrenia in children and adolescents: focus on pharmacotherapy. Drugs 2011; 71:179–208.

Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents

Diagnostic issues

Fear and worry are common in children and they are part of normal development. At the same time, anxiety disorders often begin in childhood and adolescence1 and they are the most common psychiatric disorders in this age group, with overall prevalence between 8% and 30% depending on the impairment cut-offs used.2 Anxiety disorders may be even more common in children with neurodevelopment disorders.3

In children, the more obvious clinical presentation with distress and avoidance may be masked by prominent behavioural symptoms (e.g. irritability and angry outbursts linked to avoidance). Therefore, the assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders in children needs to be undertaken by clinicians who can discriminate normal, developmentally appropriate worries, fears and shyness from anxiety disorders that significantly impair a child's functioning, and who can appreciate developmental variations in the presentation of symptoms.

Clinical guidance

Anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents often improve with age, presumably in parallel to the development of the prefrontal cortex and, in particular, executive functions. However, anxiety disorders are distressing and impairing conditions that need to be treated promptly. Chronic stress mediators may have significant impact on brain development4 and functional impairment linked to anxiety symptoms may prevent young people from accessing normative experiences that are critical for social, emotional, and cognitive development. Consistent with these detrimental effects, young people with anxiety disorders are, for example, three times more likely to have anxiety and depression in adult life compared to nonanxious youths.5

Guidelines for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents have been made available in the UK and the US. NICE guidelines focus on the treatment of social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents, suggesting the use of cognitive behavioural therapy and cautioning against the routine use of pharmacological treatment for social anxiety in this age group.6 Guidelines from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) cover the treatment of all non-obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), non-post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) anxiety disorders7. AACAP guidelines suggest multimodal treatment including psycho-education, psychotherapy (e.g. a 12-session course of exposure-based CBT), and pharmacotherapy. Drug treatment is endorsed for moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms, when impairment makes participation in psychotherapy difficult, or when psychotherapy leads to only partial response.

Prescribing for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents

Before prescribing

- Exclude other diagnoses. Anxiety symptoms can be mimicked by a range of psychiatric disorders including depression (inattention, sleep problems), bipolar disorder (irritability, sleep problems, restlessness), oppositional-defiant disorder (irritability, oppositional behaviour), psychotic disorders (social withdrawal, restlessness), ADHD (inattention, restlessness), Asperger syndrome (social withdrawal, poor social skills, repetitive behaviours and routines), and learning disabilities. They may also be mimicked by a range of endocrine (hyperthyroidism, hypoglycaemia, pheochromocytoma), neurological (migraine, seizures, delirium, brain tumours), cardiovascular (cardiac arrhythmias), and respiratory (asthma) conditions and lead intoxication. Anxiety-like symptoms can be observed in response to several drugs and substances including anti-asthma medications, sympathomimetics, steroids, SSRIs, antipsychotics (akathisia), diet pills, cold medicines, caffeine and energy drinks.

- Beware contraindications to SSRIs and potential interactions.

- Measure baseline severity. Structured interviews including the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS) and the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (Kiddie-SADS). Questionnaires including the Revised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS), Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED), or the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC). Measures of functional impairment including the Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) and the Clinical Global Impression scales (CGI)

- Obtain consent. Discuss treatment with the young person and the family (e.g. name of medication, starting/estimated ending dose, titration timeline, possible side-effects and strategies to monitor/minimise them, strategies to monitor progress, interventions for treatment-resistant cases). Document consent in writing.

What to prescribe

- SSRIs are the medications of choice for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. A Cochrane systematic review8 shows that there are seven shortterm RCTs (< 16 weeks; n treatment = 453, n control = 389) testing the efficacy of SSRIs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline) on changes in impairment for anxiety disorders in young people (CGI-I), with an overall relative risk of response of 2.38 [95% CI= 2.01–2.83] over placebo, number needed to treat (NNT) of 2–3, and no significant difference among SSRIs. The Childhood Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS) showed that monotherapy with sertraline (55% response) is as effective as CBT for anxiety (60% response) compared with placebo (24% response), and that combined therapy with sertraline and CBT is most likely to be successful (81% response).9 Sertraline, fluoxetine and fluvoxamine have been approved by the US FDA for treatment of paediatric OCD, and fluoxetine and escitalopram have been approved for treatment of paediatric depression. In 2004, the US FDA issued a Black Box warning for concerns related to worsening of depression, agitation, and suicidal ideation linked to SSRIs. These concerns were based on a review of studies of adolescents with depression rather than young people with anxiety.

- Venlafaxine was tested in two short-term RCTs (n treatment = 295, n control = 311) with an overall relative risk of response of 1.46 [95% CI= 1.25–1.71] over placebo (which was significantly lower than the overall effect of SSRIs; see above). Because of the different pharmacodynamic actions, venlafaxine could be considered a secondline treatment when SSRIs are ineffective. The evidence base for this strategy in this group of patients is, however, non-existent.

- The efficacy and safety of buspirone and mirtazapine in young people with anxiety disorders is not known, although open-label studies10,11 suggest that they might be effective in relieving anxiety symptoms.

- Benzodiazepine use is not supported by controlled trials in children,12 and may lead to paradoxical disinhibition in some children. Nevertheless, benzodiazepine use is at times considered in clinical practice to 'potentiate' therapeutic effect during initial titration of SSRIs (or to mitigate adverse effects) and for rapid tranquillisation.

A summary of the medications and doses used in the treatment of anxiety disorders is shown in Table 5.4.

Table 5.4 Typical dosage of medications for treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents

|

Medication

|

Starting dose (mg)

|

Dose range (mg)

|

|

SSRI

|

|

Sertraline

|

12.5-25

|

25-200 od

|

|

Fluoxetine

|

5-10

|

10-60 od

|

|

Fluvoxamine

|

12.5-25

|

50-200 (bd if > 50)

|

|

Paroxetine

|

5-10

|

10-40 od

|

|

Citalopram*

|

5-10

|

10-40 od

|

|

SNRI

|

|

Venlafaxine ER

|

37.5

|

37.5-225 od

|

|

5-HT1A partial agonist

|

|

Buspirone*

|

5 tds

|

15-60 od

|

|

Tetracyclic

|

|

Mirtazapine*

|

7.5-15

|

7.5-30 at night

|

|

Benzodiazepine* (prn)

|

|

Clonazepam

|

0.25-0.5

|

-

|

|

Lorazepam

|

0.5-1

|

-

|

|

Always check dose with latest formal guidance, e.g. BNF for Children.

*Treatments not supported by RCT evidence.

bd, bis die (twice a day); ER, extended release; od, omni die (once a day); prn, pro re nata (as required); SNRI, selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; tds, ter die sumendus (three times a day).

|

After prescribing

- Acute phase

- Start at low dose and titrate at regular (e.g. weekly) intervals.

- Monitor response (e.g. RCADS, SCARED, MASC, CGAS, CGI-I) frequently and systematically.

- Monitor side-effects. SSRIs are generally well tolerated during treatment for anxiety disorders in young people. However, side-effects including gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation), headache, increased motor activity, and insomnia may occur, often in mild and transient form.

- Therapeutic effect should start after 3–6 weeks of treatment but maximum effect can take up to 12–16 weeks. It is important to communicate this to families.

- If partial or non-response, consider accuracy of diagnosis, adequacy of medication trial, and compliance of patient.

- To improve response, consider: adding CBT, changing medication (e.g. switch SSRIs, other classes), or combining medications (e.g. for co-morbidities, to treat side-effects, to potentiate action).

- Maintenance phase

- Continue maintenance treatment for at least 1 year of stable improvement.

- Monitor response and side-effects regularly.

- Discontinuation phase

- Because of lack of information on long-term safety and possible improvement in symptoms with age and learning, consider discontinuing treatment after a period of stable improvement. A trial off-medication should be started at a period of low stress/demands. Discontinuation should also be considered if the medication is no longer working or the side-effects are too severe. Taper SSRIs slowly to minimise risk of withdrawal symptoms. Monitor closely for recurrence of symptoms/relapse and, if deterioration is noted, promptly restart medications.

Specific issues

Treatment of anxiety disorders in pre-school children must routinely focus on psychotherapy. In rare cases when a very young child has extreme ongoing symptoms and impairment, clinicians should reconsider diagnosis and case formulation, and reassess the adequacy of the psychotherapy trial. There are no RCTs of pharmacological interventions for anxiety in pre-school children but case reports suggest potential benefit of fluoxetine and buspirone.13

There has also been an interest in the role of pharmacological intervention to augment the effect of exposure therapy in PTSD.14 An RCT showed that administration of d-cycloserine, a partial agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor involved in fear learning and extinction, potentiates the therapeutic effect of psychotherapy in adults with social anxiety.15 No study has tested this effect in young people.

References

- Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602.

- Merikangas KR et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010; 49:980–989.

- Simonoff E et al. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008; 47:921–929.

- Danese A et al. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav 2012; 106:29–39.

- Pine DS et al. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:56–64.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment. Clinical Guideline 159, 2013. http://www.nice.org.uk/

- Connolly SD et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46:267–283.

- Ipser JC et al. Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; CD005170.

- Walkup JT et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2753–2766.

- Buitelaar JK et al. Buspirone in the management of anxiety and irritability in children with pervasive developmental disorders: results of an open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:56–59.

- Mrakotsky C et al. Prospective open-label pilot trial of mirtazapine in children and adolescents with social phobia. J Anxiety Disord 2008; 22:88–97.

- Simeon JG et al. Clinical, cognitive, and neurophysiological effects of alprazolam in children and adolescents with overanxious and avoidant disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:29–33.

- Gleason MM et al. Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46:1532–1572.

- Parsons RG et al. Implications of memory modulation for post-traumatic stress and fear disorders. Nat Neurosci 2013; 16:146–153.

- Hofmann SG et al. Augmentation of exposure therapy with d-cycloserine for social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:298–304.

Obsessive compulsive disorder in children and adolescents

The treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in children follows the same principles as in adults (see Chapter 4). Cognitive behavioural therapy is effective in this patient group and is the treatment of first choice1,2 although it may be combined with medication.3

Sertraline4–6 (from 6 years of age) and fluvoxamine (from 8 years of age) are the SSRIs licensed in the UK for the treatment of OCD in young people. Studies spanning 20 years have established the efficacy of SSRIs in the paediatric population in placebo-controlled trials. Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram and sertraline have all been shown to be efficacious and safe in young people with OCD. Clomipramine is a tricyclic with strong serotonin reuptake inhibition activity, which has been shown to be consistently superior to SSRIs5 in the paediatric population (aged 6–18 years). Clomipramine therefore remains a useful drug for some individuals, although its sideeffect profile (sedation, dry mouth, potential for cardiac side-effects) tend to limit its use in this age group. As a consequence SSRIs generally remain the recommended first choice medication for children and young people with OCD. All SSRIs appear to be equally effective, although they have different pharmacokinetics and side-effects.5 A meta-analysis of 12 RCTs of pharmacotherapy against control, in young people (under 19 years of age) showed that medication is consistently significantly more effective than placebo, and that there is no evidence that there are any clinically relevant differences between SSRIs.5

Initiation of treatment with medication

Clomipramine and SSRIs show a similar slow and incremental effect on obsessions and compulsions from as early as 1–2 weeks after initiation and placebo-referenced improvements continue for at least 24 weeks. Symptoms of depression show improvements in parallel with the OCD. In some cases, the effects can take several weeks to appear. In addition, the earliest signs of improvement may be apparent to an informant before the patient. In some instances improvements may take some months to become apparent. In light of this response profile, it is important to inform patients and their families about this, in addition to not feeling rushed to change medication because of only modest initial changes in symptoms. The use of an observer-rated quantitative measure such as the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS), may therefore be helpful to monitor progress in clinical settings.The British Association of Psychopharmacology suggest starting at the lowest dose known to be effective and waiting for up to 12 weeks before evaluating effectiveness.7 Upward dosage titration is recommended if there is insufficient clinical response. In clinical practice, a balance has to be struck between tolerability and the rate of dosage increase in busy clinical services.

Prescribing SSRIs in children

In 2004, the British Medicines and Healthcare product and Regulatory Authority agency (MHRA) cautioned against the use of SSRIs in children and young people, due to a possible increased risk of suicidal ideation.8 Subsequent reanalysis of SSRI use in depressed adolescents showed a modest two-fold rise in suicidal ideation or behaviours. There were no completed suicides in over 4400 children and adolescents. Careful reanalysis of treatment data highlights that SSRIs are clearly more efficacious in the OCD group of patients than they are in the treatment of moderate depressive episodes in children and young people. Investigators concluded that in the paediatric OCD group, the pooled risk for suicidal ideation and attempts was less than 1% across all studies. This of course is an important risk and should be explained and carefully monitored. Nonetheless, the naturalistic course of untreated OCD is that it tends not to spontaneously remit and has tremendous morbidity. Careful, judicious use of medication is therefore important in alleviating the considerable suffering caused by OCD in children and young people.

On occasion, medications (SSRIs) other than sertraline, fluvoxamine and clomipramine may be used as 'off-label' preparations with the appropriate and suitable caution. Indeed, NICE guidance9 for the treatment of OCD recommends the use of SSRIs before use of clomipramine, due to the latter drug's greater propensity for side-effects and need for cardiac monitoring. Factors guiding the choice of other medications may include issues such as the presence of other disorders (fluoxetine for OCD with comorbid depression); a good treatment response to a certain drug in other family members; the presence of other disorders, as well as cost and availability. Some children find tablets or capsules hard to swallow and there are no licensed OCD preparations available in liquid form, although 'off-label' efficacious alternatives would include fluoxetine and escitalopram.

NICE guidelines for the assessment and treatment of OCD

NICE published guidelines in 2005 on the evidence-based treatment options for OCD (and body dysmorphic disorder) for young people and adults. NICE recommends a 'stepped care' model, with increasing intensity of treatment according to clinical severity and complexity.9 The assessment of the severity and impact of OCD can be aided by the use of the CY-BOCS questionnaire, both at baseline, and as a helpful monitoring tool.10

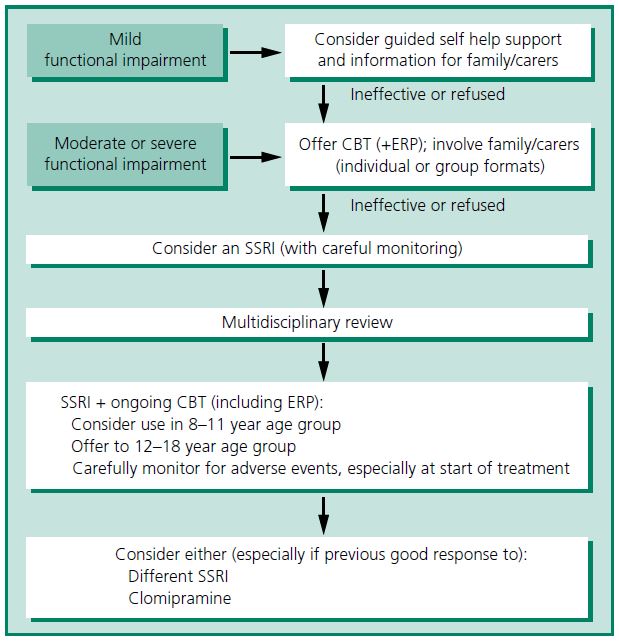

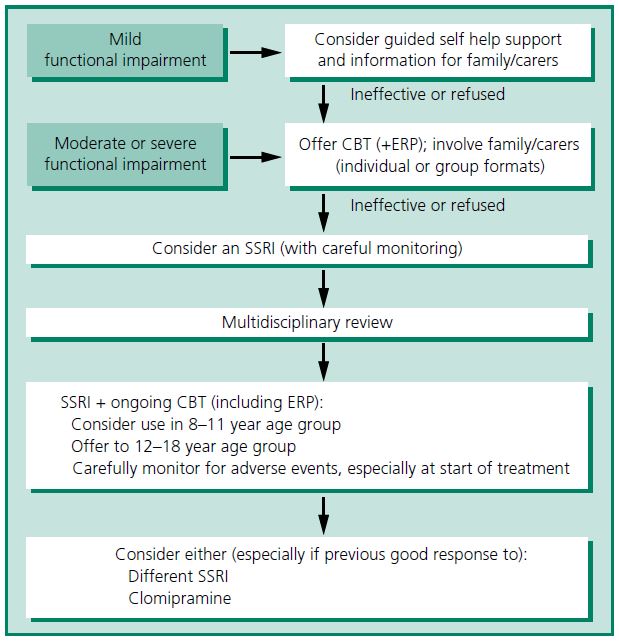

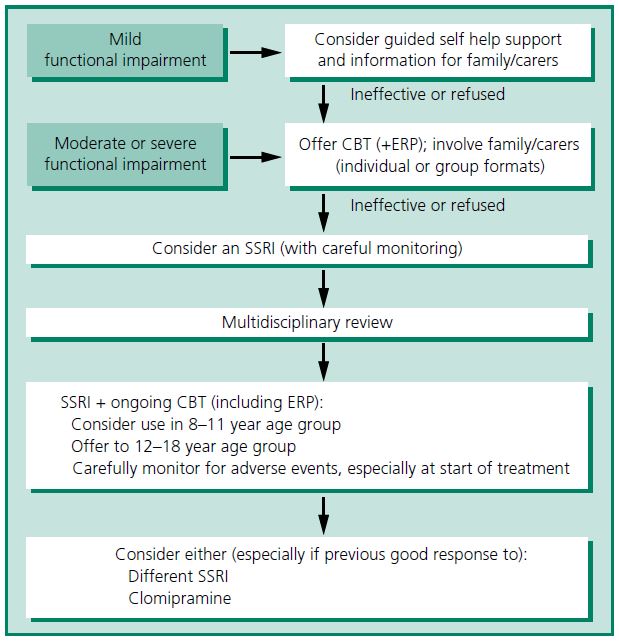

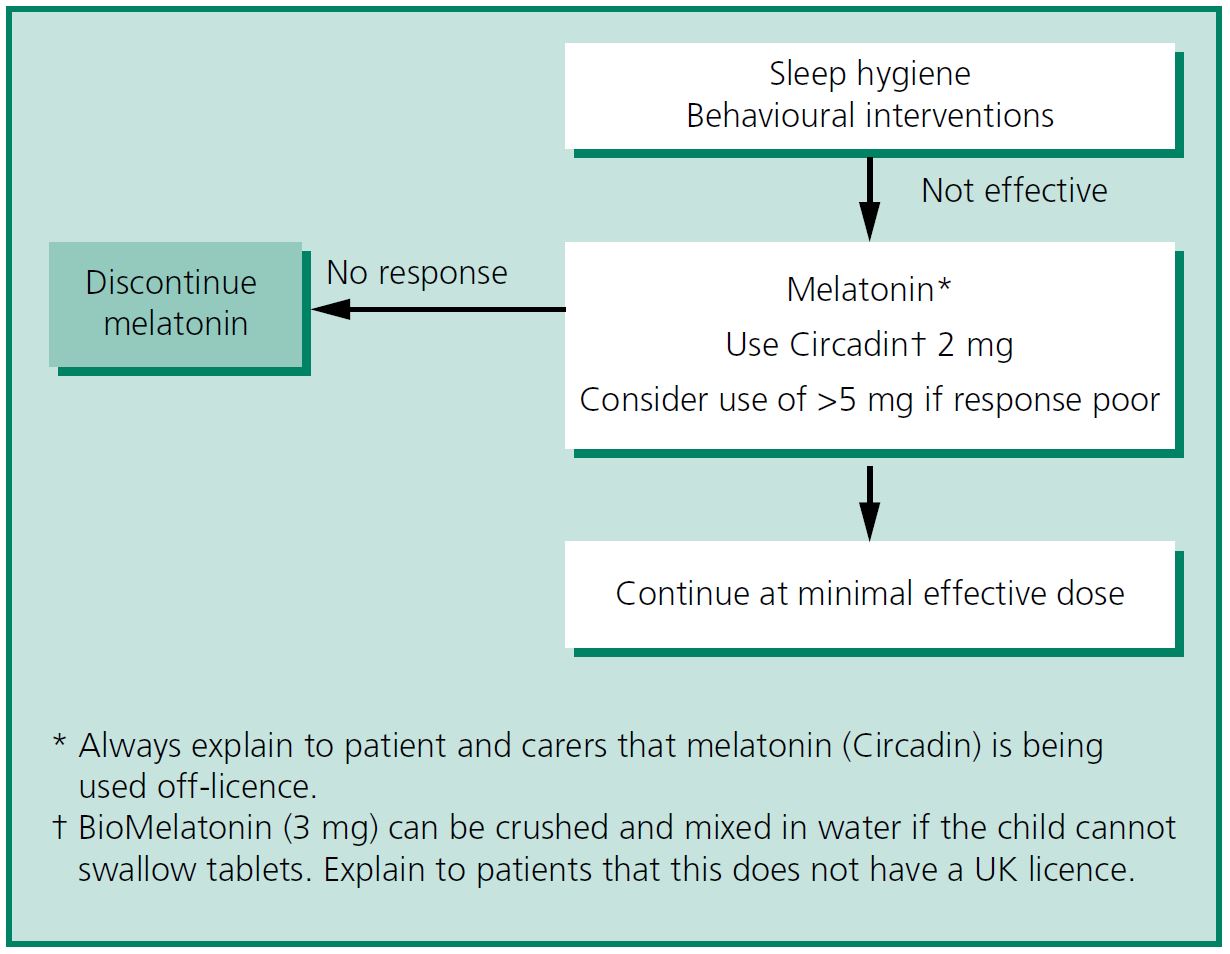

The summary treatment algorithm from the NICE guideline is shown in Figure 5.1.

CBT and medication in the treatment of childhood OCD

Medication has occasionally been used as initial treatment where there is no CBT available, or if the child is unable or unwilling to engage in CBT. Studies now show convincingly that CBT is superior to placebo and that that efforts should be made to try and ensure access to a suitably experienced CBT practitioner. On occasion, medication may be commenced before starting CBT, for instance in the context of significant co-morbid anxiety or depressed mood. Medication may also be indicated in those whose capacity to access CBT is limited by learning disabilities, although every attempt should be made to modify CBT protocols for such children.

The principle study that directly compared the efficacy of CBT, sertraline, and their combination, in children and adolescents, concluded that children with OCD should begin treatment with CBT alone or CBT plus an SSRI.2

Figure 5.1 Treatment options for children and young people with OCD. CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; ERP, exposure and response prevention; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Adapted from NICE guidance9 and reproduced from Heyman et al.11 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Treatment of refractory OCD in children

Evidence from randomised trials suggests that up to three-quarters of medicated patients make an adequate response to treatment. Roughly one-quarter of children with OCD will therefore fail to respond to an initial SSRI, administered for at least 12 weeks at the maximum tolerated dose, in combination with an adequate trial of CBT and ERP. These children should be reassessed, clarifying compliance, and ensuring that co-morbidity is not being missed. These children should usually have additional trials of at least one other SSRI. Research suggests that approximately 40% respond to a second SSRI.12 Following this, if the response is limited, a child should usually be referred to a specialist centre. Trials of clomipramine may be considered and/or augmentation with a low dose of risperidone.11,13 Research hints at the fact that using a medication with a different method of action such as risperidone or clomipramine may benefit patients who have failed to respond to two adequate SSRI trials. There is evidence that antipsychotic augmentation, as an 'off-label' therapy, can benefit patients whose response to treatment has been inadequate despite at least 3 months of maximal tolerated SSRI. Unfortunately, only one-third of treatment-resistant adult cases showed a meaningful response to this augmentation strategy. The data would therefore suggest that caution should be exercised when augmenting treatment packages for OCD in children and young people. Often children whose OCD has been difficult to treat have co-morbidities such as autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, or tic disorders. The response to medication can be differentially affected by these co-morbidities. For instance, cases with tic disorders may benefit somewhat more from augmentation with second-generation antipsychotics. Careful clinical review and reformulation is important in OCD treatment resistance. The impact of co-morbidities and wider psychosocial factors need to be considered for their impact on the treatment response overall.

Neither ketamine14 nor riluzole15 are effective in refractory childhood OCD.

Duration of treatment and long-term follow-up

Untreated OCD tends to run a chronic course. A series of adult studies have shown that discontinuation of medication tends to result in symptomatic relapse. Some authors have suggested that those with co-morbidities are at the greatest risk of relapse. Given that studies frequently exclude cases with additional co-morbidities, it is likely that the relapse rates have been underestimated. NICE guidelines recommend that if a young person has responded to medication, treatment should continue for at least 6 months after remission. Clinical experience would suggest that when discontinuation of treatment is attempted it should be done slowly, cautiously and in a transparent manner with the patient and their family. Once again, the careful use of clinical outcome measures should be considered when stopping medication. The role of maintenance CBT and medication is under increasing scrutiny. Both appear to offer promise in maintaining gains made after initial treatment. It is important that throughout childhood, adolescence and into adult life, the individual with OCD should have access to health-care professionals, treatment opportunities and other support as needed, and NICE recommends that if relapse occurs, people with OCD should be seen as soon as possible rather than placed on a routine waiting list.

References

- O'Kearney RT et al. Behavioural and cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; CD004856.

- Freeman JB et al. Cognitive behavioral treatment for young children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61:337–343.

- Mancuso E et al. Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2010; 20:299–308.

- The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study Team (POTS). Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 292:1969–1976.

- Geller DA et al. Which SSRI? A meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy trials in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1919–1928.

- March JS et al. Treatment benefit and the risk of suicidality in multicenter, randomized, controlled trials of sertraline in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006; 16:91–102.

- Baldwin DS et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2014; 28:403–439.

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants. London: MHRA; 2004. http://www.mhra.gov.uk

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Core interventions in the treatment of obsessivecompulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Clinical Guideline 31, 2005. http://www.nice.org.uk.