Chapter 3

Bipolar affective disorder

Lithium is an element that the body handles in a similar way to sodium. The ubiquitous nature of sodium in the human body, its involvement in a wide range of biological processes, and the potential for lithium to alter these processes, has made it extremely difficult to ascertain the key mechanism(s) of action of lithium in regulating mood. For example, there is some evidence that people with bipolar illness have higher intracellular concentrations of sodium and calcium than controls, and that lithium can reduce these. Reduced activity of sodium-dependent intracellular second messenger systems has been demonstrated, as have modulation of dopamine and serotonin neurotransmitter pathways, reduced activity of protein kinase C and reduced turnover of arachidonic acid. Lithium may also have neuroprotective effects, possibly mediated through its effects on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) pathways. For a review see Marmol (2008).1 It is notable that, with the exception of a database study linking lithium use with a reduced risk of developing dementia,2 literature pertaining to the possible neuroprotective effect of lithium reports largely on either in vitro or animal studies. The clinical literature is rather more dominated by reports of neurotoxicity.3

Lithium is effective in the treatment of moderate to severe mania with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 6.4 Its use for this indication is limited by the fact that it usually takes at least a week to achieve a response5 and that the co-administration of antipsychotics may increase the risk of neurological side-effects. It can also be difficult to achieve therapeutic plasma levels rapidly and monitoring can be problematic if the patient is uncooperative.

The main indication for lithium is in the prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder where it reduces both the number and the severity of relapses.6 Lithium is more effective at preventing manic than depressive relapse;7 the NNT to prevent relapse into mania or depression has been calculated to be 10 and 14 respectively.7 Lithium also offers some protection against antidepressant-induced hypomania. It is generally clinically appropriate to initiate prophylactic treatment: (1) after a single manic episode that was associated with significant risk and adverse consequences; (2) in the case of bipolar I illness, two or more acute episodes; or (3) in the case of bipolar II illness, significant functional impairment, frequent episodes or significant risk of suicide.8 NICE supports the use of lithium as a first-line mood stabiliser; lithium alone is probably more effective than valproate alone,9 with the combination being better still.10 The earlier in the course of the illness that lithium treatment is started, the better the response is likely to be.11

Lithium augmentation of an antidepressant in patients with unipolar depression is recommended by NICE as a next-step treatment in patients who have not responded to standard antidepressant drugs.12 A recent meta-analysis found lithium to be three times as effective as placebo for this indication with a NNT of 5,13 although the response rate in STAR-D was more modest (see section on 'Refractory depression' in Chapter 4).

The effectiveness of lithium in treating mood disorders does not go unchallenged. For a review, see Moncrieff.14

Lithium is also used to treat aggressive15 and self-mutilating behaviour, to both prevent and treat steroid-induced psychosis,16 and to raise the white blood cell count in patients receiving clozapine.

It is estimated that 15% of people with bipolar affective disorder take their own life.17 A meta-analysis of clinical trials concluded that lithium reduced by 80% the risk of both attempted and completed suicide in patients with bipolar illness,18,19 and two large database studies have shown that lithium-treated patients were less likely to complete suicide than patients treated with divalproex20 or with other mood stabilising drugs (valproate, gabapentin, carbamazepine).21

In patients with unipolar depression, lithium also seems to protect against suicide; the effect size being slightly smaller than that seen in bipolar illness.19,22 The mechanism of this protective effect is unknown.

A recent systematic review of the relationship between plasma levels and response in patients with bipolar illness concluded that the minimum effective plasma level for prophylaxis is 0.4 mmol/L, with the optimal range being 0.6–0.75 mmol/L. Levels above 0.75 mmol/L offer additional protection only against manic symptoms.8,23 Changes in plasma levels seem to worsen the risk of relapse.24 The optimal plasma level range in patients who have unipolar depression is less clear.13

Children and adolescents may require higher plasma levels than adults to ensure that an adequate concentration of lithium is present in the central nervous system (CNS).25

Lithium is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract but has a long distribution phase. Blood samples for plasma lithium level estimations should be taken 10–14 hours (ideally 12) post dose in patients who are prescribed a single daily dose of a prolongedrelease preparation at bedtime.26

There is no clinically significant difference in the pharmacokinetics of the two most widely prescribed brands of lithium in the UK: Priadel and Camcolit. Other preparations should not be assumed to be bioequivalent and should be prescribed by brand.

Lack of clarity over which liquid preparation is intended when prescribing can lead to the patient receiving a sub-therapeutic or toxic dose.

Most side-effects are dose- (and therefore plasma level) related. These include mild gastro-intestinal upset, fine tremor, polyuria and polydipsia. Polyuria may occur more frequently with twice-daily dosing.27 Propranolol can be useful in lithium-induced tremor. Some skin conditions such as psoriasis and acne can be aggravated by lithium therapy. Lithium can also cause a metallic taste in the mouth, ankle oedema and weight gain.

Lithium can cause a reduction in urinary concentrating capacity—nephrogenic diabetes insipidus—hence the occurrence of thirst and polyuria. This effect is usually reversible in the short to medium term but may be irreversible after long-term treatment (> 15 years).26,27 Lithium treatment can also lead to a reduction in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR);28 the magnitude of the risk is uncertain.29,30 One large cross-sectional study found that one-third of young people prescribed lithium had an e-GFR of < 60 mLs/ minute (chronic kidney disease stage 3).28 A very small number of patients may develop interstitial nephritis. Lithium levels of > 0.8 mmol/L are associated with a higher risk of renal toxicity.23

In the longer term, lithium increases the risk of hypothyroidism;31 in middle-aged women, the risk may be up to 20%.32 A case has been made for testing thyroid autoantibodies in this group before starting lithium (to better estimate risk) and for measuring thyroid function tests (TFTs) more frequently in the first year of treatment.33 Hypothyroidism is easily treated with thyroxine. TFTs usually return to normal when lithium is discontinued. Lithium also increases the risk of hyperparathyroidism, and some recommend that calcium levels should be monitored in patients on long-term treatment.33 Clinical consequences of chronically increased serum calcium include renal stones, osteoporosis, dyspepsia, hypertension and renal impairment.33

For a review of the toxicity profile of lithium, see McKnight et al.34

Toxic effects reliably occur at levels > 1.5 mmol/L and usually consist of gastro-intestinal effects (increasing anorexia, nausea and diarrhoea) and CNS effects (muscle weakness, drowsiness, ataxia, course tremor and muscle twitching). Above 2 mmol/L, increased disorientation and seizures usually occur, which can progress to coma, and ultimately death. In the presence of more severe symptoms, osmotic or forced alkaline diuresis should be used (note NEVER thiazide or loop diuretics). Above 3 mmol/L peritoneal or haemodialysis is often used. These plasma levels are only a guide and individuals vary in their susceptibility to symptoms of toxicity.

Most risk factors for toxicity involve changes in sodium levels or the way the body handles sodium. For example low salt diets, dehydration, drug interactions (see Table 3.1) and some uncommon physical illnesses such as Addison's disease.

Information relating to the symptoms of toxicity and the common risk factors should always be given to patients when treatment with lithium is initiated.35 This information should be repeated at appropriate intervals to make sure that it is clearly understood.

Before prescribing lithium, renal, thyroid and cardiac function should be checked. As a minimum, e-GRF36 and TFTs should be checked. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is also recommended in patients who have risk factors for, or existing, cardiovascular disease. A baseline measure of weight is also desirable.

Lithium is a human teratogen. Women of child-bearing age should be advised to use a reliable form of contraception. See section on 'Pregnancy' in Chapter 7.

Table 3.1 Lithium: prescribing and monitoring

|

Indications |

Mania, hypomania, prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder and recurrent depression. Reduces aggression and suicidality |

|

Pre-lithium work up |

e-GRF and TFTs. ECG recommended in patients who have risk factors for, or existing cardiovascular disease. Baseline measure of weight desirable |

|

Prescribing |

Start at 400 mg at night (200 mg in the elderly). Plasma level after 7 days, then 7 days after every dose change until the desired level is reached (0.4 mmol/L may be effective in unipolar depression, 0.6-1.0 mmol/L in bipolar illness, slightly higher levels in difficult to treat mania). Blood should be taken 12 hours after the last dose. Take care when prescribing liquid preparations to clearly specify the strength required |

|

Monitoring |

Plasma lithium every 6 months (more frequent monitoring is necessary in those prescribed interacting drugs, the elderly and those with established renal impairment or other relevant physical illness). e-GFR and TFTs every 6 months. Weight (or BMI) should also be monitored |

|

Stopping |

Reduce slowly over at least 1 month. Avoid incremental reductions in plasma levels of > 0.2 mmol/L |

|

BMI, body mass index; ECG, electrocardiogram; e-GFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; TFT, thyroid function test. |

|

NICE recommend that plasma lithium, e-GFR and TFTs should be checked every 6 months. More frequent tests may be required in those who are prescribed interacting drugs, elderly or have established chronic kidney disease (CKD). A patient safety alert related to the importance of biochemical monitoring in patients prescribed lithium has been issued by the National Patient Safety Agency.37 Weight (or BMI) should also be monitored. Lithium monitoring in clinical practice in the UK is known to be suboptimal,38 although there has been a modest improvement over time.39 The use of automated reminder systems has been shown to improve monitoring rates.40

Intermittent treatment with lithium may worsen the natural course of bipolar illness. A much greater than expected incidence of manic relapse is seen in the first few months after discontinuing lithium,41 even in patients who have been symptom free for as long as 5 years.42 This has led to recommendations that lithium treatment should not be started unless there is a clear intention to continue it for at least 3 years.43 This advice has obvious implications for initiating lithium treatment against a patient's will (or in a patient known to be non-compliant with medication) during a period of acute illness.

The risk of relapse is reduced by decreasing the dose gradually over a period of at least a month,44 and avoiding decremental serum level reductions of > 0.2 mmol/L.23 The course of illness may, however, still be adversely affected: a recent naturalistic study found that, in patients who had been in remission for at least 2 years and had discontinued lithium very slowly, the recurrence rate was at least three times greater than in patients who continued lithium; significant survival differences persisted for many years. Patients maintained on high lithium levels prior to discontinuation were particularly prone to relapse.45

One large US study based on prescription records found that half of those prescribed lithium took almost all of their prescribed doses, a quarter took between 50 and 80%, and the remaining quarter took less than 50%. In addition one-third of patients took lithium for less than 6 months in total.46 A large audit found that one in ten patients prescribed long-term lithium treatment had a plasma level below the therapeutic range.47 It is clear that sub-optimal adherence limits the effectiveness of lithium in clinical practice. One database study suggested the extent to which lithium was taken was directly related to the risk of suicide (more prescriptions= lower suicide rate).48

Less convincing data support the emergence of depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar illness after lithium discontinuation.41 There are few data relating to patients with unipolar depression.

Because of lithium's relatively narrow therapeutic index, pharmacokinetic interactions with other drugs can precipitate lithium toxicity. Most clinically significant interactions are with drugs that alter renal sodium handling; see Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Lithium: clinically relevant drug interactions

|

Drug group |

Magnitude of effect |

Timescale of effect |

Additional information |

|

ACE inhibitors |

Unpredictable Up to four-fold increases in [Li] |

Develops over several weeks |

Seven-fold increased risk of hospitalisation for lithium toxicity in the elderly Angiotensin II receptor antagonists may be associated with similar risk |

|

Thiazide diuretics |

Unpredictable Up to four-fold increases in [Li] |

Usually apparent in first 10 days |

Loop diuretics are safer Any effect will be apparent in the first month |

|

NSAIDs |

Unpredictable From 10% to > four-fold increases in [Li] |

Variable; few days to several months |

NSAIDs are widely used on a prn basis Can be bought without a prescription |

|

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; [Li], lithium; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. |

|||

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors can (1) reduce thirst which can lead to mild dehydration, and (2) increase renal sodium loss leading to increased sodium re-absorption by the kidney, resulting in an increase in lithium plasma levels. The magnitude of this effect is variable; from no increase to a four-fold increase. The full effect can take several weeks to develop. The risk seems to be increased in patients with heart failure, dehydration and renal impairment (presumably because of changes in fluid balance/handling). In the elderly, ACE inhibitors increase seven-fold the risk of hospitalisation due to lithium toxicity. ACE inhibitors can also precipitate renal failure so, if co-prescribed with lithium, more frequent monitoring of e-GFR and plasma lithium is required.

The following drugs are ACE inhibitors: captopril, cilazapril enalapril, fosinopril, imidapril, lisinopril, moexipril, perindopril, quinapril, ramipril and trandolapril.

Care is also required with angiotensin II receptor antagonists; candesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan and valsartan.

Diuretics can reduce the renal clearance of lithium, the magnitude of this effect being greater with thiazide than loop diuretics. Lithium levels usually rise within 10 days of a thiazide diuretic being prescribed; the magnitude of the rise is unpredictable and can vary from an increase of 25% to 400%.

The following drugs are thiazide (or related) diuretics: bendroflumethiazide, chlortalidone, cyclopenthiazide, indapamide, metolazone and xipamide.

Although there are case reports of lithium toxicity induced by loop diuretics, many patients receive this combination of drugs without apparent problems. The risk of an interaction seems to be greatest in the first month after the loop diuretic has been prescribed and extra lithium plasma level monitoring during this time is recommended if these drugs are co-prescribed. Loop diuretics can increase sodium loss and subsequent re-absorption by the kidney. Patients taking loop diuretics may also have been advised to restrict their salt intake; this may contribute to the risk of lithium toxicity in these individuals.

The following drugs are loop diuretics: bumetanide, furosemide and torasemide.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit the synthesis of renal prostaglandins, thereby reducing renal blood flow and possibly increasing renal re-absorption of sodium and therefore lithium. The magnitude of the rise is unpredictable for any given patient; case reports vary from increases of around 10% to over 400%. The onset of effect also seems to be variable; from a few days to several months. Risk appears to be increased in those patients who have impaired renal function, renal artery stenosis or heart failure and who are dehydrated or on a low salt diet. There are a growing number of case reports of an interaction between lithium and cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors.

NSAIDs (or COX-2 inhibitors) can be combined with lithium, but (1) they should be prescribed regularly NOT prn, and (2) more frequent plasma lithium monitoring is essential.

Some NSAIDs can be purchased without a prescription, so it is particularly important that patients are aware of the potential for interaction.

The following drugs are NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors: aceclofenac, acemetacin, celecoxib, dexibuprofen, dexketofrofen, diclofenac, diflunisal, etodolac, etoricoxib, fenbufen, fenoprofen, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, indometacin, ketoprofen, lumiracoxib, mefenamic acid, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, piroxicam, sulindac, tenoxicam and tiaprofenic acid.

There are rare reports of neurotoxicity when carbamazepine is combined with lithium. Most are old and in the context of treatment involving high plasma lithium levels. It is of note though that carbamazepine can cause hyponatraemia, which may in turn lead to lithium retention and toxicity. Similarly, rare reports of CNS toxicity implicate selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), another group of drugs that can cause hyponatraemia.

Valproate is a simple branched-chain fatty acid. Its mechanism of action is complex and not fully understood. Valproate inhibits the catabolism of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), reduces the turnover of arachidonic acid, activates the extracellular signalregulated kinase (ERK) pathway thus altering synaptic plasticity, interferes with intracellular signaling, promotes brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and reduces levels of protein kinase C. Recent research has focused on the ability of valproate to alter the expression of multiple genes that are involved in transcription regulation, cytoskeletal modifications and ion homeostasis. Other mechanisms that have been proposed include depletion of inositol, and indirect effects on non-GABA pathways through inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels.

There is a growing literature relating to the potential use of valproate as an adjunctive treatment in several types of cancer; the relevant mechanism of action being inhibition of histone deacetylase.2–4

Valproate is available in the UK in three forms: sodium valproate and valproic acid (licensed for the treatment of epilepsy), and semi-sodium valproate, licensed for the treatment of acute mania. Both semi-sodium and sodium valproate are metabolised to valproic acid, which is responsible for the pharmacological activity of all three preparations.5 Clinical studies of the treatment of affective disorders variably use sodium valproate, semi-sodium valproate, 'valproate' or valproic acid. The great majority have used semi-sodium valproate (divalproex in the US).

In the US, valproic acid is widely used in the treatment of bipolar illness,6 and in the UK sodium valproate is widely used. It is important to remember that doses of sodium valproate and semi-sodium valproate are not equivalent; a slightly higher (approximately 10%) dose is required if sodium valproate is used to allow for the extra sodium content.

It is unclear if there is any difference in efficacy between valproic acid, valproate semi-sodium and sodium valproate. One large US quasi-experimental study found that inpatients who initially received the semi-sodium preparation had a hospital stay that was a third longer than patients who initially received valproic acid.7 Note that sodium valproate controlled release (Epilim Chrono) can be administered as a once-daily dose whereas other sodium and semi-sodium valproate preparations require at least twicedaily administration.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown valproate to be effective in the treatment of mania,8,9 with a response rate of 50% and a NNT of 2–4,10 although large negative studies do exist.11 One RCT found lithium to be more effective overall than valproate9 but a large (n = 300) randomized open trial of 12 weeks duration found lithium and valproate to be equally effective in the treatment of acute mania.12 Valproate may be effective in patients who have failed to respond to lithium; in a small placebo controlled RCT (n = 36) in patients who had failed to respond to or could not tolerate lithium, the median decrease in Young Mania Rating Scale scores was 54% in the valproate group and 5% in the placebo group.13 It may be less effective than olanzapine, both as monotherapy14 as an adjunctive treatment to lithium12 in acute mania. A network meta-analysis reported that valproate was less effective but better tolerated than lithium.15

A meta-analysis of four small RCTs concluded that valproate is effective in bipolar depression with a small to medium effect size,16 although further data are required.10

Although open label studies suggest that valproate is effective in the prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder,17 RCT data are limited.18,19 Bowden et al.20 found no difference between lithium, valproate and placebo in the primary outcome measure, time to any mood episode, although valproate was superior to lithium and placebo on some secondary outcome measures. This study can be criticised for including patients who were 'not ill enough' and for not lasting 'long enough' (1 year). In another RCT,18 which lasted for 47 weeks, there was no difference in relapse rates between valproate and olanzapine. The study had no placebo arm and the attrition rate was high, so is difficult to interpret. A post-hoc analysis of data from this study found that patients with rapid cycling illness had a better very early response to valproate than to olanzapine but that this advantage was not maintained.19 Outcomes with respect to manic symptoms for those who did not have a rapid cycling illness were better at 1 year with olanzapine than valproate. In a further 20 month RCT of lithium versus valproate in patients with rapid cycling illness, both the relapse and attrition rate were high, and no difference in efficacy between valproate and lithium was apparent.21 More recently, the BALANCE study found lithium to be numerically superior to valproate, and the combination of lithium and valproate statistically superior to valproate alone.22 Aripiprazole in combination with valproate is superior to valproate alone.23

NICE recommends valproate as a first-line option for the treatment of acute episodes of mania, in combination with an antidepressant for the treatment of acute episodes of depression, and for prophylaxis,24 but importantly NOT in women of child-bearing potential.24,25 Cochrane conclude that the evidence supporting the use of valproate as prophylaxis is limited,26 yet use for this indication has substantially increased in recent years.27

Valproate is sometimes used to treat aggressive behaviours of variable aetiology.28 One small RCT (n = 16) failed to detect any advantage for risperidone augmented with valproate over risperidone alone in reducing hostility in patients with schizophrenia.29 A mirror-image study found that, in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in a secure setting, valproate decreased agitation.30

There is a small positive placebo controlled RCT of valproate in generalised anxiety disorder.31

The pharmacokinetics of valproate are complex, following a three-compartmental model and showing protein-binding saturation. Plasma level monitoring is supposedly of more limited use than with lithium or carbamazepine.32 There may be a linear association between valproate serum levels and response in acute mania, with serum levels < 55 mg/L being no more effective than placebo and levels > 94 mg/L being associated with the most robust response,33 although these data are weak.32 Note that this is the top of the reference range (for epilepsy) that is quoted on laboratory forms. Optimal serum levels during the maintenance phase are unknown, but are likely to be at least 50 mg/L.34 Achieving therapeutic plasma levels rapidly using a loading dose regimen is generally well tolerated. Plasma levels can also be used to detect non-compliance or toxicity.

Valproate can cause both gastric irritation and hyperammonaemia,35 both of which can lead to nausea. Lethargy and confusion can occasionally occur with starting doses above 750 mg/day. Weight gain can be significant,36 particularly when valproate is used in combination with clozapine. Valproate causes dose related tremor in up to one-quarter of patients.37 In the majority of these patients it is intention/postural tremor that is problematic, but a very small proportion develop parkinsonism associated with cognitive decline; these symptoms are reversible when valproate is discontinued.38

Hair loss with curly regrowth and peripheral oedema can occur, as can thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, red cell hypoplasia and pancreatitis.39 Valproate can cause hyperandrogenism in women40 and has been linked with the development of polycystic ovaries; the evidence supporting this association is conflicting. Valproate is a major human teratogen (see section on 'Pregnancy' in Chapter 7). Valproate may very rarely cause fulminant hepatic failure. Young children receiving multiple anticonvulsants are most at risk. Any patient with raised liver function tests (LFTs) (common in early treatment41) should be evaluated clinically and other markers of hepatic function, such as albumin and clotting time, should be checked.

Many side-effects of valproate are dose-related (peak plasma-level related) and increase in frequency and severity when the plasma level is > 100 mg/L. The once daily chrono form of sodium valproate does not produce as high peak plasma levels as the conventional formulation, and so may be better tolerated.

Valproate and other anticonvulsant drugs have been associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviour,42 but this finding is not consistent across studies.43 Patients with depression44 or who take another anticonvulsant drug that increases the risk of developing depression may be a sub-group at greater risk.45

Note that valproate is eliminated mainly through the kidneys, partly in the form of ketone bodies, and may give a false positive urine test for ketones.

Baseline full blood count (FBC), LFTs, and weight or BMI, are recommended by NICE.

NICE recommend that a FBC and LFTs should be repeated after 6 months, and that BMI should be monitored. Valproate summary of product characteristics (SPCs) recommend more frequent LFTs during the first 6 months, with albumin and clotting measured if enzyme levels are abnormal.

It is unknown if abrupt discontinuation of valproate worsens the natural course of bipolar illness in the same way that discontinuation of lithium does. One small naturalistic retrospective study suggests that it might.46 Until further data are available, if valproate is to be discontinued, it should be done slowly over at least a month.

Valproate is an established human teratogen. NICE recommend that alternative anticonvulsants are preferred in women with epilepsy47 and that valproate should not be used to treat bipolar illness in women of child-bearing age.24

The SPCs for sodium valproate and semi-sodium valproate48,49 state that:

Women who have mania are likely to be sexually disinhibited. The risk of unplanned pregnancy is likely to be above population norms (where 50% of pregnancies are unplanned). If valproate cannot be avoided, adequate contraception should be ensured and prophylactic folate prescribed.

The teratogenic potential of valproate is not widely appreciated and many women of child-bearing age are not advised of the need for contraception or prophylactic folate.50,51 Valproate may also cause impaired cognitive function in children exposed to valproate in utero.52 See section on 'Pregnancy' in Chapter 7.

Valproate is highly protein bound and can be displaced by other protein-bound drugs, such as aspirin, leading to toxicity. Aspirin also inhibits the metabolism of valproate; a dose of at least 300 mg aspirin is required.53 Other, less strongly protein-bound drugs, such as warfarin, can be displaced by valproate, leading to higher free levels and toxicity. Valproate is hepatically metabolised; drugs that inhibit CYP enzymes can increase valproate levels (e.g. erythromycin, fluoxetine and cimetidine). Valproate can increase the plasma levels of some drugs, possibly by inhibition/competitive inhibition of their metabolism. Examples include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (particularly clomipramine54), lamotrigine,55 quetiapine,56 warfarin57 and phenobarbital. Valproate may also significantly lower plasma olanzapine concentrations; the mechanism is unknown.58

Pharmacodynamic interactions also occur. The anticonvulsant effect of valproate is antagonised by drugs that lower the seizure threshold (e.g. antipsychotics). Weight gain can be exacerbated by other drugs such as clozapine and olanzapine.

The prescribing and monitoring of valproate are summarised in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Valproate: prescribing and monitoring

|

Indications |

Mania, hypomania, bipolar depression and prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder May reduce aggression in a range of psychiatric disorders (data weak) Note that sodium valproate is licensed only for epilepsy and semi-sodium valproate only for acute mania |

|

Pre-valproate work up |

FBC and LFTs. Baseline measure of weight desirable |

|

Prescribing |

Titrate dose upwards against response and side-effects. Loading doses can be used and are generally well tolerated Note that controlled release sodium valproate (Epilim Chrono) can be given once daily. All other formulations must be administered at least twice daily Plasma levels can be used to ensure adequate dosing and treatment compliance. Blood should be taken immediately before the next dose |

|

Monitoring |

FBC and LFTs if clinically indicated Weight (or BMI) |

|

Stopping |

Reduce slowly over at least 1 month |

|

BMI, body mass index; FBC, full blood count; LFT, liver function test. |

|

Carbamazepine blocks voltage-dependent sodium channels thus inhibiting repetitive neuronal firing. It reduces glutamate release and decreases the turnover of dopamine and nor-adrenaline. Carbamazepine has a similar molecular structure to TCAs.

As well as blocking voltage-dependent sodium channels, oxcarbazepine also increases potassium conductance and modulates high-voltage activated calcium channels.

Carbamazepine is available as a liquid, chewable, immediate-release and controlled-release tablets. Conventional formulations generally have to be administered twoto three-times daily. The controlled release preparation can be given once or twice daily, and the reduced fluctuation in serum levels usually leads to improved tolerability. This preparation has a lower bioavailability and an increase in dose of 10–15% may be required.

Carbamazepine is primarily used as an anticonvulsant in the treatment of grand mal and focal seizures. It is also used in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and, in the UK, is licensed for the treatment of bipolar illness in patients who do not respond to lithium.

With respect to the treatment of mania, two placebo-controlled randomised studies have found the extended-release formulation of carbamazepine to be effective; in both studies, the response rate in the carbamazepine arm was twice that in the placebo arm.2,3 Carbamazepine was not particularly well tolerated; the incidence of dizziness, somnolence and nausea was high. Another study found carbamazepine alone to be as effective as carbamazepine plus olanzapine.4 NICE does not recommend carbamazepine as a first-line treatment for mania.5

Open studies suggest that carbamazepine monotherapy has some efficacy in bipolar depression;6 note that the evidence base supporting other strategies is stronger (see section on 'Bipolar depression' in this chapter). Carbamazepine may also be useful in unipolar depression either alone7 or as an augmentation strategy.8

Carbamazepine is generally considered to be less effective than lithium in the prophylaxis of bipolar illness;9 several published studies report a low response rate and high drop-out rate. A meta-analysis (n = 464) failed to find a significant difference in efficacy between lithium and carbamazepine, but those who received carbamazepine were more likely to drop out of treatment because of side-effects.10 Lithium is considered to be superior to carbamazepine in reducing suicidal behaviour,11 although data are not consistent.12 NICE considers carbamazepine to be a third-line prophylactic agent.5 Three small studies suggest the related oxcarbazepine may have some prophylactic efficacy when used in combination with other mood stabilising drugs.13–15

There are data supporting the use of carbamazepine in the management of alcohol withdrawal symptoms,16 although the high doses required initially are often poorly tolerated. Cochrane does not consider the evidence strong enough to support the use of carbamazepine for this indication.17 Carbamazepine has also been used to manage aggressive behaviour in patients with schizophrenia;18 the quality of data is weak and the mode of action unknown. There are a number of case reports and open case series that report on the use of carbamazepine in various psychiatric illnesses such as panic disorder, borderline personality disorder and episodic dyscontrol syndrome.

When carbamazepine is used as an anticonvulsant, the therapeutic range is generally considered to be 4–12 mg/L, although the supporting evidence is not strong. In patients with affective illness, a dose of at least 600 mg/day and a plasma level of at least 7 mg/L may be required,19 although this is not a consistent finding.4,7,20 Levels above 12 mg/L are associated with a higher side-effect burden.

Carbamazepine serum levels vary markedly within a dosage interval. It is therefore important to sample at a point in time where levels are likely to be reproducible for any given individual. The most appropriate way of monitoring is to take a trough level before the first dose of the day.

Carbamazepine is a hepatic enzyme inducer that induces its own metabolism as well as that of other drugs. An initial plasma half-life of around 30 hours is reduced to around 12 hours on chronic dosing. For this reason, plasma levels should be checked 2–4 weeks after an increase in dose to ensure that the desired level is still being obtained.

Most published clinical trials that demonstrate the efficacy of carbamazepine as a mood stabiliser use doses that are significantly higher (800–1200 mg/day) than those commonly prescribed in UK clinical practice.21

The main side-effects associated with carbamazepine therapy are dizziness, diplopia, drowsiness, ataxia, nausea and headaches. They can sometimes be avoided by starting with a low dose and increasing slowly. Avoiding high peak blood levels by splitting the dose throughout the day, or using a controlled release formulation, may also help. Dry mouth, oedema and hyponatraemia are also common. Sexual dysfunction can occur, probably mediated through reduced testosterone levels.22 Around 3% of patients treated with carbamazepine develop a generalised erythematous rash. Serious exfoliative dermatological reactions can rarely occur; vulnerability is genetically determined,23 and genetic testing of people of Han Chinese or Thai origin is recommended before carbamazepine is prescribed. Carbamazepine is a known human teratogen (see section on 'Pregnancy' in Chapter 7).

Carbamazepine commonly causes a chronic low white blood cell (WBC) count. One patient in 20,000 develops agranulocytosis and/or aplastic anaemia.24 Raised alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) are common (a GGT of 2–3 times normal is rarely a cause for concern25). A delayed multi-organ hypersensitivity reaction rarely occurs, mainly manifesting itself as various skin reactions, a low WBC count, and abnormal LFTs. Fatalities have been reported.25,26 There is no clear timescale for these events.

Some anticonvulsant drugs have been associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviour. Carbamazepine has not been implicated, either in general,27,28 or more specifically, in those with bipolar illness.29

Baseline U&Es, FBC and LFTs are recommended by NICE. A baseline measure of weight is also desirable.

NICE recommend that U&Es, FBC and LFTs should be repeated after 6 months, and that weight (or BMI) should also be monitored.

It is not known if abrupt discontinuation of carbamazepine worsens the natural course of bipolar illness in the same way that abrupt cessation of lithium does. In one small case series (n = 6), one patient developed depression within 1 month of discontinuation,30 while in another small case series (n = 4), three patients had a recurrence of their mood disorder within 3 months.31 Until further data are available, if carbamazepine is to be discontinued, it should be done slowly (over at least a month).

Carbamazepine is an established human teratogen (see section on 'Pregnancy' in Chapter 7).

Women who have mania are likely to be sexually disinhibited. The risk of unplanned pregnancy is likely to be above population norms (where 50% of pregnancies are unplanned). If carbamazepine cannot be avoided, adequate contraception should be ensured (note the interaction between carbamazepine and oral contraceptives outlined below) and prophylactic folate prescribed.

Carbamazepine is a potent inducer of hepatic cytochrome enzymes and is metabolised by CYP3A4. Plasma levels of most antidepressants, most antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, some cholinesterase inhibitors, methadone, thyroxine, theophylline, oestrogens and other steroids may be reduced by carbamazepine, resulting in treatment failure. Patients requiring contraception should either receive a preparation containing not less than 50 μg oestrogen or use a non-hormonal method. Drugs that inhibit CYP3A4 will increase carbamazepine plasma levels and may precipitate toxicity. Examples include cimetidine, diltiazem, verapamil, erythromycin and some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Pharmacodynamic interactions also occur. The anticonvulsant activity of carbamazepine is reduced by drugs that lower the seizure threshold (e.g. antipsychotics and antidepressants), the potential for carbamazepine to cause neutropenia may be increased by other drugs that have the potential to depress the bone marrow (e.g. clozapine), and the risk of hyponatraemia may be increased by other drugs that have the potential to deplete sodium (e.g. diuretics). Neurotoxicity has been reported when carbamazepine is used in combination with lithium. This is rare.

Table 3.4 Carbamazepine: prescribing and monitoring

|

Indications |

Mania (not first line), bipolar depression (evidence weak), unipolar depression (evidence weak), and prophylaxis of bipolar disorder (third line after antipsychotics and valproate). Alcohol withdrawal (may be poorly tolerated) Carbamazepine is licensed for the treatment of bipolar illness in patients who do not respond to lithium |

|

Pre-carbamazepine work up |

U&Es, FBC and LFTs. Baseline measure of weight desirable |

|

Prescribing |

Titrate dose upwards against response and side effects; start with 100-200 mg bd and aim for 400 mg bd (some patients will require higher doses) Note that the modified release formulation (Tegretol Retard) can be given once to twice daily, is associated with less severe fluctuations in serum levels, and is generally better tolerated Plasma levels can be used to assure adequate dosing and treatment compliance. Blood should be taken immediately before the next dose. Carbamazepine induces its own metabolism; serum levels (if used) should be re-checked a month after an increase in dose |

|

Monitoring |

U&Es, FBC and LFTs if clinically indicated Weight (or BMI) |

|

Stopping |

Reduce slowly over at least 1 month |

|

bd, bis in die (twice a day); BMI, body mass index; FBC, full blood count; LFT, liver function test, U&E, urea and electrolytes. |

|

As carbamazepine is structurally similar to TCAs, in theory it should not be given within 14 days of discontinuing a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI).

The prescribing and monitoring of carbamazepine is summarised in Table 3.4.

It is unhelpful to think of antipsychotic drugs as having only 'antipsychotic' actions. Individual antipsychotics variously possess sedative, anxiolytic, antimanic, mood-stabilising and antidepressant properties. Some antipsychotics (quetiapine and olanzapine) show all of these activities.

First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) have long been used in mania and several studies support their use in a variety of hypomanic and manic presentations.1–3 Their effectiveness seems to be enhanced by the addition of a mood stabiliser.4,5 In the longer-term treatment of bipolar affective disorder, FGAs are widely used (presumably as prophylaxis)6 but robust supporting data are absent.7 The observation that typical antipsychotics are associated with both depression and tardive dyskinesia in bipolar patients militates against their long-term use.7–9 Certainly the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) seems less likely to cause depression than treatment with haloperidol.10 The use of FGA depots is common in practice but poorly supported and seems to be associated with a high risk of depression.11

Among newer antipsychotics, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole and asenapine have been most robustly evaluated and are licensed in many countries for the treatment of mania. Olanzapine is more effective than placebo in mania,12,13 and at least as effective as valproate semi-sodium14,15 and lithium.16,17 As with FGAs, olanzapine may be most effective when used in combination with a mood-stabiliser18,19 (although in one study, olanzapine + carbamazepine was no better than carbamazepine alone20). Data suggest olanzapine may offer benefits in longer-term treatment;21,22 it may be more effective than lithium,23 and it is formally licensed as prophylaxis.

Data relating to quetiapine24–26 suggest robust efficacy in all aspects of bipolar affective disorder including prevention of bipolar depression.27 Aripiprazole is effective in mania both alone28–30 and as an add-on agent,31 and in long-term prophylaxis.32,33 Clozapine seems to be effective in refractory bipolar conditions, including refractory mania.34–37 Risperidone has shown efficacy in mania,38 particularly in combination with a mood-stabiliser.2,39 Risperidone long acting injection is also effective40 (note though that the pharmacokinetics of this formulation generally render it an unsuitable choice for the acute treatment of mania). There are few data for amisulpride41 rather more for ziprasidone42 and effectively none for lurasidone (notwithstanding its effect as an acute treatment for bipolar depression43,44) or iloperidone.

Asenapine is given by the sublingual route and is effective in mania.45,46 Efficacy seems to be maintained in the longer term.47 Asenapine is less sedative than olanzapine with a similar (low) propensity for akathisia and other movement disorders46,47 and is less likely than olanzapine to cause weight gain and metabolic disturbance.48

Overall, antipsychotics (particularly haloperidol, olanzapine and risperidone) may be more effective than traditional mood stabilisers in the treatment of mania,49 and quetiapine is similarly effective but better tolerated than aripiprazole or lithium.49

Drug treatment is the mainstay of therapy for mania and hypomania. Both antipsychotics and so-called mood stabilisers are effective. Sedative and anxiolytic drugs (e.g. benzodiazepines) may add to the effects of these drugs. Drug choice is made difficult by the dearth of direct comparisons and so no drug can be recommended over another on efficacy grounds. However, a multiple treatments meta-analysis1 (which allows indirect comparison) suggested that olanzapine, risperidone haloperidol and quetiapine had the best combination of efficacy and acceptability. The added benefit of antipsychotic–mood stabiliser combinations (compared with mood-stabiliser alone) is established for those relapsing while on mood stabilisers, but unclear for those presenting on no treatment.2–6

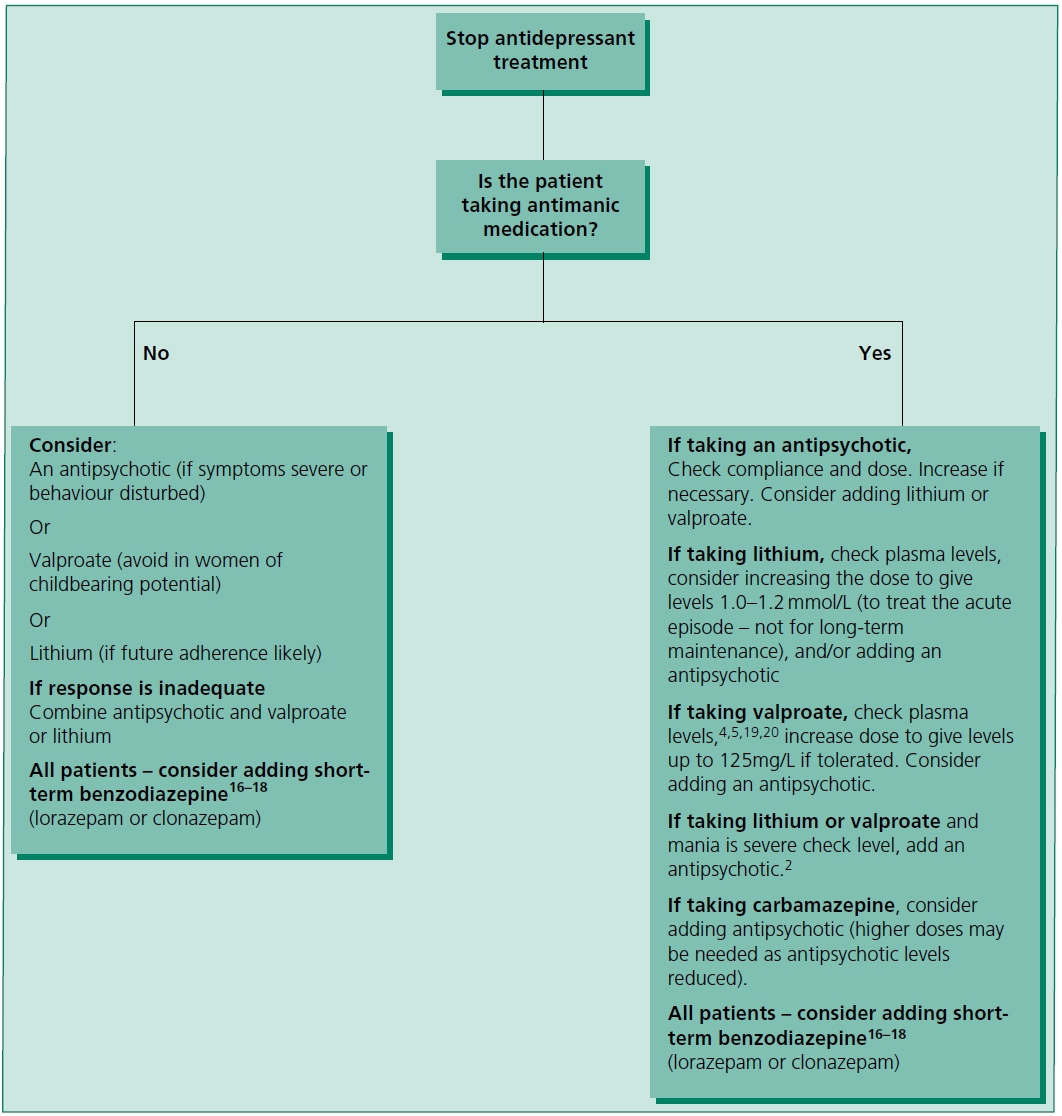

Figure 3.1 Treatment of acute mania or hypomania.2–15 Note that lithium may be relatively less effective in mixed states21 or substance misuse.22

Figure 3.1 outlines a treatment strategy for mania and hypomania. These recommendations are based on UK NICE guidelines,3 the British Association of Psychopharmacology guidelines,4 American Psychiatric Association guidelines5 and individual references cited. Where an antipsychotic is recommended, choose from those licensed for mania/ bipolar disorder, i.e. most conventional drugs (see individual labels/SPCs), aripiprazole, asenapine, olanzapine, risperidone and quetiapine.

Those drugs with the best evidence for effective treatment of mania are shown in Table 3.5. Other possible treatments are shown in Table 3.6. The relative costs of drugs for the treatment of mania in the UK are shown in Table 3.7.

Table 3.5 Drug treatment of mania: suggested doses

|

Drug |

Dose |

|

Lithium |

400 mg/day, increasing every 3-4 days according to plasma levels. At least one study has used 800 mg as a starting dose23 |

|

Valproate |

As semi-sodium: 250 mg three-times daily increasing according to tolerability and plasma levels. Slow release semi-sodium valproate may also be effective (at 15-30 mg/kg)24 but there is one failed study25 As sodium valproate slow release - 500 mg/day increasing as above Higher, so-called loading doses, have been used, both oral26-28 and intravenous.29,30 Dose is 20-30 mg/kg/day |

|

Aripiprazole |

15 mg/day increasing up to 30 mg/day as required31,32 |

|

Asenapine |

5 mg bd increasing to 10 mg bd as required |

|

Olanzapine |

10 mg/day increasing to 15 mg or 20 mg as required |

|

Risperidone |

2 mg or 3 mg/day increased to 6 mg/day as required |

|

Quetiapine |

IR - 100 mg/day increasing to 800 mg as required. Higher starting doses have been used33 ER - 300 mg/day increasing to 600 mg/day on day 2 |

|

Haloperidol |

5-10 mg/day increasing to 15 mg if required |

|

Lorazepam17,18 |

Up to 4 mg/day (some centres use higher doses) |

|

Clonazepam16,18 |

Up to 8 mg/day |

|

bd, bis in die (twice a day); ER, extended release; IR, immediate release. |

|

Table 3.6 Other possible drug treatments for mania (listed in alphabetical order)

|

Treatment |

Comments |

|

Allopurinol34 (600 mg/day) |

Clear therapeutic effect when added to lithium in one RCT (n = 120), but no effect in a smaller recent study35 |

|

Clozapine36,37 |

Established treatment option for refractory mania/bipolar disorder |

|

Gabapentin38-40 (up to 2.4 g/day) |

Probably only effective by virtue of an anxiolytic effect. Rarely used. Possibly useful as prophylaxis41 |

|

Lamotrigine42,43 (up to 200 mg/day) |

Possibly effective but better evidence for bipolar depression |

|

Levetiracetam44,45 (up to 4000 mg/day) |

Possibly effective but controlled studies required |

|

Memantine46 (10-30 mg/day) |

Small open study |

|

Oxcarbazepine47-53 (around 300-3000 mg/day) |

Probably effective acutely and as prophylaxis although one controlled study conducted (in youths) was negative54 |

|

Phenytoin55 (300-400 mg/day) |

Rarely used. Limited data. Complex kinetics with narrow therapeutic range |

|

Ritanserin56 (10 mg/day) |

Supported by a single RCT. Well tolerated. May protect against EPS |

|

Tamoxifen57-59 (10-140 mg/day) |

Possibly effective. Three small RCTs. Dose-response relationship unclear, but 80 mg/day clearly effective when added to lithium |

|

Topiramate60-63 (up to 300 mg/day) |

Possibly effective. Causes weight loss but poorly tolerated |

|

Tryptophan depletion64 |

Supported by a small RCT |

|

Ziprasidone65-67 |

Supported by three RCTs |

|

Consult specialist and primary literature before using any treatment listed. EPS, extrapyramidal side-effects; RCT, randomised controlled trial. |

|

Table 3.7 Drugs for acute mania: relative costs

|

Drug |

Cost |

Comments |

|

Lithium (Priadel) |

£+ |

Add cost of plasma level monitoring |

|

Carbamazepine (Tegretol Retard) |

£++ |

Self-induction complicates acute treatment; reduces plasma levels of other drugs |

|

Sodium valproate (Epilim Chrono) |

£++ |

Not licensed for mania, but may be given once daily |

|

Valproate semi-sodium (Depakote) |

£++ |

Licensed for mania, but given two or three times daily |

|

Aripiprazole (Ability) |

£+++ |

Non-sedative, but effective. Patent near expiration in most countries |

|

Haloperidol (generic) |

£+ |

Most widely used typical antipsychotic in mania |

|

Asenapine (Sycrest) |

£+++ |

Sublingual only. Licensed for mania only |

|

Olanzapine (generic) |

£+ |

Velotabs or equivalent may be more expensive |

|

Quetiapine (generic - IR) |

£+ |

ER preparation branded in some countries |

|

Risperidone (generic) |

£+ |

Non-sedative but effective |

| ER, extended release; IR, immediate release. | ||

Bipolar depression is a common and debilitating disorder which differs from unipolar disorder in severity, time course, recurrence and response to drug treatment. Episodes of bipolar depression are, compared with unipolar depression, more rapid in onset, more frequent, more severe, shorter and more likely to involve delusions and reverse neurovegetative symptoms such as hyperphagia and hypersomnia.1–3 Around 15% of people with bipolar affective disorder commit suicide,4 a statistic which aptly reflects the severity and frequency of depressive episodes. Bipolar depression affords greater socio-economic burden than either mania and unipolar depression5 and represents the majority of symptomatic illness in bipolar affective disorder in respect to time.6,7

The drug treatment of bipolar depression is somewhat controversial for two reasons. First, until recently there were few well-conducted, randomised, controlled trials specifically in bipolar depression and second, the condition entails consideration of lifelong outcome rather than simply discrete episode response.8 We have some knowledge of the therapeutic effects of drugs in bipolar depressive episodes but more limited awareness of the therapeutic or deleterious effects of drugs in the longer term. In the UK, NICE recommends the initial use of fluoxetine combined with olanzapine or quetiapine on its own (assuming an antipsychotic is not already prescribed).9 Lamotrigine is considered to be second-line treatment (although we consider the evidence for lamotrigine rather weak). Tables 3.8, 3.9 and 3.10 give some broad guidance on treatment options in bipolar depression.

Table 3.8 Established treatments for bipolar depression (listed in alphabetical order)

|

Drug/regime |

Comments |

|

Lamotrigine1,10,11-16 |

Lamotrigine appears to be effective both as a treatment for bipolar depression and as prophylaxis against further episodes. It does not induce switching or rapid cycling. It is as effective as citalopram and causes less weight gain than lithium. Overall, the effect of lamotrigine is modest, with numerous failed trials.17,18 It may be useful as an adjunct to lithium19 or as an alternative to it in pregnancy20 Treatment is somewhat complicated by the small risk of rash, which is associated with speed of dose titration. The necessity for titration may limit clinical utility A further complication is the question of dose: 50 mg/day has efficacy, but 200 mg/day is probably better. In the USA doses of up to 1200 mg/day have been used (mean around 250 mg/day) |

|

Lithium and antidepressant21-28 |

Antidepressants are still widely used in bipolar depression, particularly for breakthrough episodes occurring in those on mood stabilisers. They have been assumed to be effective-although there is a risk of cycle acceleration and/or switching. Studies suggest mood stabilisers alone are just as effective as mood stabilisers/antidepressant combination.29,30 Tricyclic antidepressants and MAOIs are usually avoided. SSRIs are generally recommended if an antidepressant is to be prescribed. Venlafaxine and bupropion (amfebutamone) have also been used. Venlafaxine may be more likely to induce a switch to mania.31,32 There is controversial evidence that antidepressants are effective only when lithium plasma levels are below 0.8 mmol/L Continuing antidepressant treatment after resolution of symptoms may protect against depressive relapse-33,34 although only in the absence of a mood stabiliser.35 At the time of writing, there is no consensus on whether or not to continue antidepressants long term36 |

|

Lithium1,10,37-39 |

Lithium is probably effective in treating bipolar depression but supporting data are methodologically questionable.40 There is some evidence that lithium prevents depressive relapse but its effects on manic relapse are considered more robust. Fairly strong support for lithium in reducing suicidality in bipolar affectivedisorder41,42 |

|

Lurasidone |

Two RCTs show good effect for lurasidone either alone43 or as an adjunct to mood stabilisers.44 Not licensed for bipolar depression in the UK at the time of writing. |

|

Olanzapine +/- |

This combination (Symbyax®) is more effective than both placebo and olanzapine alone in treating bipolar depression. The dose is 6 mg and 25 mg or 12 mg and 50 mg/day (so presumably 5/20 mg and 10/40 mg are effective). May be more effective than lamotrigine. Reasonable evidence of prophylactic effect. Recommended as first-line treatment by NICE9 Olanzapine alone is effective when compared with placebo-49 but the combination with fluoxetine is more effective. (This is possibly the strongest evidence for a beneficial effect for an antidepressant in bipolar depression.) |

|

Quetiapine50-54 |

Five large RCTs have demonstrated clear efficacy for doses of 300 mg and 600 mg daily (as monotherapy) in bipolar I and bipolar II depression. May be superior to both lithium and paroxetine Quetiapine also prevents relapse into depression and mania55,56 and so one of the treatments of choice in bipolar depression.57 It appears not to be associated with switching to mania |

|

Valproate1,10,57-61 |

Limited evidence of efficacy as monotherapy but recommended in some guidelines. Several very small RCTs but many negative. Probably protects against depressive relapse but database is small |

|

MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SSRI. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. |

|

Table 3.9 Alternative drug treatments for bipolar depression

|

Drug/regime |

Comments |

|

Antidepressants62-70 |

'Unopposed' antidepressants (i.e. without mood-stabiliser protection) are generally avoided in bipolar depression because of the risk of switching. There is also evidence that they are relatively less effective (perhaps not effective at all) in bipolar depression than in unipolar depression. Nonetheless short-term use of fluoxetine, venlafaxine and moclobemide seems reasonably effective and safe even as monotherapy. Overall, however, unopposed antidepressant treatment should be avoided, especially in bipolar I disorder36 |

|

Carbamazepine1,10,71 |

Occasionally recommended but database is poor and effect modest. May have useful activity when added to other mood-stabilisers |

|

Pramipexole72,73 |

Pramipexole is a dopamine agonist which is widely used in Parkinson's disease. Two small placebo-controlled trials suggest useful efficacy in bipolar depression. Effective dose averages around 1.7 mg/day. Both studies used pramipexole as an adjunct to existing mood-stabiliser treatment. Neither study detected an increased risk of switching to mania/hypomania (a theoretical consideration) but data are insufficient to exclude this possibility. Probably best reserved for specialist centres |

|

Refer to primary literature before using. |

|

Table 3.10 Other possible treatments for bipolar depression

|

Drug/regime |

Comments |

|

Aripiprazole74-77 |

Limited support from open studies as add-on treatment. RCT negative. Possibly not effective |

|

Gabapentin1,78,79 |

Open studies suggest modest effect when added to mood-stabilisers or antipsychotics. Doses average around 1750 mg/day. Anxiolytic effect may account for apparent effect in bipolar depression |

|

Inositol80 |

Small-randomised-pilot study suggests that 12 g/day inositol is effective in bipolar depression |

|

Ketamine81-83 |

A single IV dose of 0.5 mg/kg is effective in refractory bipolar depression. Very high response rate. Dissociative symptoms common but brief. Risk of ulcerative cystitis if repeatedly used |

|

Mifepristone84,85 |

Some evidence of mood-elevating properties in bipolar depression. May also improve cognitive function. Dose is 600 mg/day |

|

Modafinil86,87 |

One positive RCT as adjunct to mood-stabiliser. Dose is 100-200 mg/day. Positive RCT with amodafinil 150 mg/day |

|

Omega-3 fatty acids88,89 |

One positive RCT (1 g/2 g a day) and one negative (6 g a day) |

|

Riluzole90,91 |

Riluzole shares some pharmacological characteristics with lamotrigine. Database is limited to a single case report supporting use in bipolar depression |

|

Thyroxine92 |

Limited evidence of efficacy as augmentation. Doses average around 300 μg/day. One failed RCT93 |

|

Zonisamide94-97 |

Supported by several open-label studies. Dose is 100-300 mg a day |

|

Seek specialist advice before using. |

|

Meta-analytic studies in bipolar depression are constrained by the variety of methods used to assess efficacy. This means that many scientifically robust studies cannot be included in some meta-analyses because their parameters (outcomes, duration, etc.) do not match, and so cannot be compared with other studies. Early lithium studies are an important example—their short duration and cross-over design precludes their inclusion in meta-analysis. A meta-analysis of five trials (906 participants) revealed that antidepressants were no better than placebo in respect to response or remission, although results approached statistical significance.76 Another analysis of trials not involving antidepressants98 (7,307 participants) found a statistical advantage over placebo for olanzapine + fluoxetine, valproate, quetiapine, lurasidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole and carbamazepine (in order of effect size, highest first).

The largest analysis is a multiple treatments meta-analysis of 29 studies including 8,331 subjects.99 Overall olanzapine + fluoxetine, lurasidone, olanzapine, valproate, SSRIs and quetiapine were ranked highest in terms of effect size and response with olanzapine + fluoxetine ranked first for both.

The combination of olanzapine + fluoxetine is probably the most effective treatment available for bipolar depression (other SSRIs may be effective but should be avoided unless clear individual benefit is obvious36). Other first-line choices are quetiapine, olanzapine, lurasidone and valproate. These drugs differ substantially in adverse effect profile, tolerability and cost, each of which needs to be considered when prescribing for an individual. Lithium and lamotrigine are also effective but supporting evidence is relatively weak (although clinical experience is, in contrast, vast). Aripiprazole, risperidone, ziprasidone, tricyclics and MAOIs are probably not effective and should not be used.99

Rapid cycling is usually defined as bipolar affective disorder in which four or more episodes of (hypo) mania or depression occur in a 12-month period. It is generally held to be less responsive to drug treatment than non-rapid-cycling bipolar illness1,2 and entails considerable depressive morbidity and suicide risk.3 Table 3.11 outlines a treatment strategy for rapid cycling based on rather limited data and very few direct comparisons of drugs.4,5 This strategy is broadly in line with the findings of a recent systematic review.5 NICE conclude that there is no evidence to support rapid-cycling illness being managed any differently from that with a more conventional course.6 Lithium, alone or in combination with valproate, would therefore be first-line treatment. An alternative would be to add an antipsychotic with proven activity in bipolar affective disorder and/or rapid cycling (see below).

In practice, response to treatment is sometimes idiosyncratic: individuals may show significant response only to one or two drugs. Spontaneous or treatment-related remissions occur in around one-third of rapid-cyclers7 and rapid cycling may come and go in most patients.8 Non-drug methods may also be considered.9,10

Table 3.11 Recommended treatment strategy for rapid-cycling bipolar affective disorder

|

Step |

Suggested treatment |

|

Step 1 |

Withdraw antidepressants in all patients11-15

|

|

Step 2 |

Evaluate possible precipitants (e.g. alcohol, thyroid dysfunction, external stressors) 2 |

|

Step 3 |

Optimise mood stabiliser treatment18-21 (using plasma levels), and

|

|

Step 4 |

Consider other (usually adjunct) treatment options

|

| Choice of drug is determined by patient factors—few comparative efficacy data to guide choice at the time of writing. Quetiapine probably has best supporting data32–34 and may be considered treatment of choice. Olanzapine is probably second choice.5 Conversely, supporting data for levetiracetam, nimodipine, thyroxine and topiramate are rather limited. | |

The median duration of mood episodes in people with bipolar affective disorder has been reported to be 13 weeks, with a quarter of patients remaining unwell at 1 year.1 Most people with bipolar affective disorder spend much more time depressed than manic,2 and bipolar depression can be very difficult to treat. The suicide rate in bipolar illness is increased 25-fold over population norms and the vast majority of suicides occur during episodes of depression.3 Mixed states are also common and present an increased risk of suicide.4

Note that residual symptoms after an acute episode are a strong predictor of recurrence.1,5 Most evidence supports the efficacy of lithium6–10 in preventing episodes of mania and depression. Carbamazepine is somewhat less effective10,11 and the long-term efficacy of valproate is uncertain,8,9,12–14 although it too may protect against relapse both into depression and mania.10,15 Lithium has the advantage of a proven anti-suicidal effect16–18 but perhaps, relative to other mood stabilisers, the disadvantage of a worsened outcome following abrupt discontinuation.19–22

The BALANCE study found that valproate as monotherapy was relatively less effective than lithium or the combination of lithium and valproate,13 casting doubt on its use as a first-line single treatment. Also, a large observational study has shown that lithium is much more effective than valproate in preventing relapse to any condition and in preventing rehospitalisation.23 Given this and the fact that valproate is not licensed for prophylaxis, it should now be considered a second-line treatment.

Conventional antipsychotics have traditionally been used and are perceived to be effective although the objective evidence base is, again, weak.24,25 FGA depots protect against mania but may worsen depression.26 Evidence supports the efficacy of some SGAs, particularly olanzapine,9,27 quetiapine,28 aripiprazole29 and risperidone.30 Olanzapine, quetiapine and aripiprazole are licensed for prophylaxis and appear to protect against both mania and depression. Whether SGAs are more effective than FGAs, or are truly associated with a reduced overall side-effect burden, remains untested.

A significant proportion of patients with bipolar illness fail to be treated adequately with a single mood-stabiliser,13 so combinations of mood-stabilisers31,32 or a mood-stabiliser and an antipsychotic32,33 are commonly used.34 Also, there is evidence that where combination treatments are effective in mania or depression, then continuation with the same combination provides optimal prophylaxis.28,33 The use of polypharmacy needs to be balanced against the likely increased side-effect burden. Combinations of olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine or haloperidol with lithium or valproate are recommend by NICE.27 Alternative antipsychotics are also options in combinations with lithium or valproate, particularly if these have been found to be effective during the treatment of an acute episode of mania or depression28,35 Carbamazepine is considered to be third line. Lamotrigine may be useful in bipolar II disorder27 but seems only to prevent recurrence of depression.36 Extrapolation of currently available data suggests that lithium plus a SGA is probably the polypharmacy regimen of choice.

A meta-analysis of long-term antidepressant treatment found that the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent a new episode of depression was larger than the number needed to harm (NNH) related to precipitating a new episode of mania.37 The STEP-BD study found no significant benefit for continuing (compared with discontinuing) an antidepressant and worse outcomes in those with rapid-cycling illness.38 There is thus essentially no support for long-term use of antidepressants in bipolar illness, although they continue to be widely used.

Substance misuse increases the risk of switching into mania.39

First line: lithium

Second line: valproate (NOT in women of child-bearing age), olanzapine, or quetiapine

Third line: alternative antipsychotic that has been effective during an acute episode, carbamazepine, lamotrigine

Table 3.12 Physical monitoring for people with bipolar affective disorder*

|

Test or measurement |

Monitoring for all patients |

Additional monitoring for specific drugs |

||||

|

Initial health check |

Annual check up |

Antipsychotics |

Lithium |

Valproate |

Carbamazepine |

|

|

Thyroid function |

Yes |

Yes |

|

At start and every 6 months; more often if evidence of deterioration |

|

|

|

Liver function |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

At start and periodically during treatment if clinically indicated |

At start and periodically during treatment if clinically indicated |

|

Renal function (e-GFR) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

At start and every 6 months; more often if there is evidence of deterioration of the patient starts taking interacting drugs |

|

|

|

Urea and electrolytes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

At start and then every 6 months (include serum calcium) |

|

Every 6 months. More often if clinically indicated |

|

Full blood count |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Only if clinically indicated |

At start and 6 months |

At start and at 6 months |

|

Blood (plasma) glucose |

Yes |

Yes, as part of a routine physical health check |

At start and then every 4-6 months (and at 1 month if taking olanzapine); more often if evidence of elevated levels |

|

|

|

|

Lipid profile |

Yes |

Yes, as part of a routine physical health check |

At start and at 3 months; more often initially if evidence of elevated levels |

|

|

|

|

Blood pressure |

Yes |

Yes, as part of a routine physical health check |

During dosage titration if antipsychotic prescribed is associated with postural hypotension |

|

|

|

|

Prolactin |

Children and adolescents only |

|

At start and if symptoms of raised prolactin develop Raised prolactin unlikely with quetiapine or aripiprazole. Very occasionally seen with olanzapine and asenapine. Very common with risperidone and FGAs |

|

|

|

|

ECG |

If indicated by history or clinical picture |

|

At start if there are risk factors for, or existing, cardiovascular disease (or haloperidol is prescribed). If relevant abnormalities are detected, as a minimum recheck after each dose increase |

At start if risk factors for or existing cardiovascular disease. If relevant abnormalities are detected, as a minimum recheck after each dose increase |

|

At start if risk factors for or existing cardiovascular disease. If relevant abnormalities are detected, as a minimum recheck after each dose increase |

|

Weight |

|

Yes, as part of a routine physical health check |

At start then frequently for first 3 months then three monthly for first year. Thereafter, at least annually |

At start, and when needed if the patient gains weight rapidly |

At start and when needed if the patient gains weight rapidly |

At start and when needed if the patient gains weight rapidly |

|

Plasma levels of drug |

|

|

|

At least 3-4 days after initiation and 3-4 days after every dose change until levels stable, then every 3 months in the first year, then every 6 months for most patients (see NICE1) |

Titrate by effect and tolerability. Do not routinely measure unless there is evidence of lack of effectiveness, poor adherence or toxicity |

Two weeks after initiation and two weeks after dose change. Thereafter, do not routinely measure unless there is evidence of lack of effectiveness, poor adherence or toxicity |

|

For patients on lamotrigine, do an annual health check, but no special monitoring tests are needed |

||||||

|

*Based on NICE Guidelines1 and NPSA advice.2 ECG, electrocardiogram; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FGA, first-generation antipsychotics. |

||||||