CHAPTER 33

Supportive Psychotherapy

Supportive psychotherapy is a broadly defined approach with wide applicability and is the most extensively practiced form of individual psychotherapy. In fact, research studies agree with clinical observations that supportive psychotherapy is effective for a broad range of conditions and may be as efficacious as expressive psychotherapy (Hellerstein et al. 1998; Winston and Winston 2002).

The concept of supportive psychotherapy was developed early in the twentieth century to describe a treatment approach with objectives more limited than the goals of expressive psychotherapy. The objective of supportive psychotherapy was not to change the patient's personality but to help the patient cope with symptoms, prevent relapse of serious mental illness, or help a relatively healthy person deal with a crisis or transient problem. As defined in earlier years, supportive psychotherapy is a body of techniques, such as praise, advice, exhortation, and encouragement, embedded in psychodynamic understanding and used to treat severely impaired patients. Based on this definition, supportive psychotherapy was denigrated in early papers on psychotherapy as the "copper" of direct suggestion compared with the "pure gold" of psychoanalysis (Freud 1919/1955). Anything other than psychoanalysis was "nothing but suggestion" (Glover 1931). Even more recently, Stewart (1985) came to the disparaging conclusion that "the highly trained psychiatrist may be tempted to delve too deeply in supportive psychotherapy and often is not as effective as someone less extensively trained" (p. 1360).

Supportive psychotherapy can now be defined as a dyadic treatment that uses direct measures to ameliorate symptoms and maintain, restore, or improve self-esteem, ego function, and adaptive skills (Pinsker 1997; Winston et al. 2012). To accomplish these objectives, treatment may involve examination of relationships, real or transferential, and examination of both past and current patterns of emotional response or behavior. Selfesteem involves the patient's sense of efficacy, confidence, hope, and self-regard. Ego or structural functions include relation to reality, thinking, defenses, object relations, regulation of affect, synthetic function, and others (Winston et al. 2012). Ego functions are alternatively called psychological functions by cognitive-behavioral therapists whose formulations do not include the ego as a component of a mental apparatus. Adaptive skills are actions associated with effective functioning in multiple spheres. It should be noted that the boundary between ego functions and adaptive skills is not sharply defined. The patient's assessment of events is an ego function; the action he or she takes in response to the assessment is an adaptive skill.

Supportive psychotherapy is based on a number of theoretical approaches (Table 33-1) that must be integrated by the therapist in the treatment of individual patients (Winston and Winston 2002).

Psychoanalytic theory is generally viewed as the basis for supportive psychotherapy, with an emphasis on ego psychology and development (Hartmann 1958; Mahler et al. 1975), object relations theory (Fairbairn 1952; Winnicott 1965), self psychology issues (Kohut 1971), interpersonal and relational approaches (Aron 1996; Mitchell 1988), and attachment theory (Bowlby 1988). The emphasis in supportive psychotherapy is on relational/interpersonal issues and the self within the reality of the present everyday world, as opposed to working on conflict and instinctual issues and focusing on the past. A supportive patient-therapist relationship provides the patient the safety to access and acknowledge painful experiences and beliefs. The therapist serves as an attachment figure providing a secure base for the patient. A major outgrowth of the psycho analytic/dynamic approach is the conceptualization of the psychopathology-psychotherapy continuum, which matches the patient's psychopathology to the appropriate treatment (see section "The Psychopathology-Psychotherapy Continuum" later in the chapter).

|

Table 33-1. Theoretical approaches |

|

|

Psychoanalytic, including ego psychology and development object relations self psychology interpersonal and relational attachment Cognitive-behavioral Learning theory |

|

Supportive psychotherapy also utilizes many ideas and techniques derived from cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Cognitive-behavioral techniques are an indispensable part of supportive psychotherapy and can be used for targeted problems such as panic, depression, phobias, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and dysfunctional thinking (Pinsker 1997; Winston and Winston 2002).

Learning theory can also contribute to the techniques of supportive psychotherapy, but unfortunately learning theory has not been incorporated into most forms of psychotherapy in a systematic fashion. A great deal of supportive psychotherapy can be conceptualized as a form of teaching, a process of imparting knowledge. In general, learning is the cognitive process of acquiring skill or knowledge. Memory is the retention of learned information. Psychotherapy can be considered a controlled form of learning (Etkin et al. 2005), through the acquisition of a combination of skills and knowledge. Learning does not take place as a simple recording process. Learning requires active processing during psychotherapy sessions through an interpretive process in which new information is stored by relating it to what an individual already knows. From this perspective, it is important for the therapist to facilitate effective processing during psychotherapy sessions using the techniques of interpretation, elaboration, generation, and critical reflection, which are described later in this chapter in the section "Interventions." In addition, teaching and learning are of great importance in supportive psychotherapy in helping patients learn about their illness and about how to behave in a more adaptive manner.

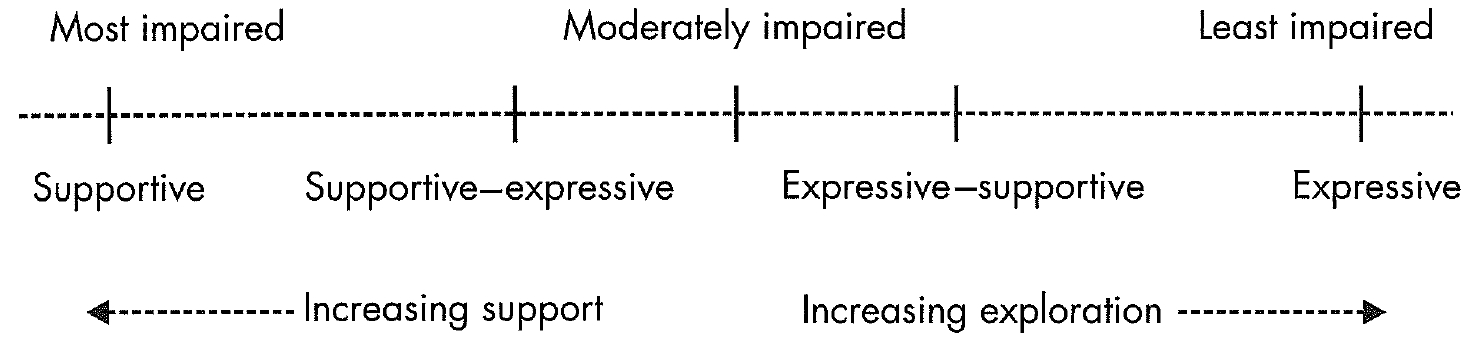

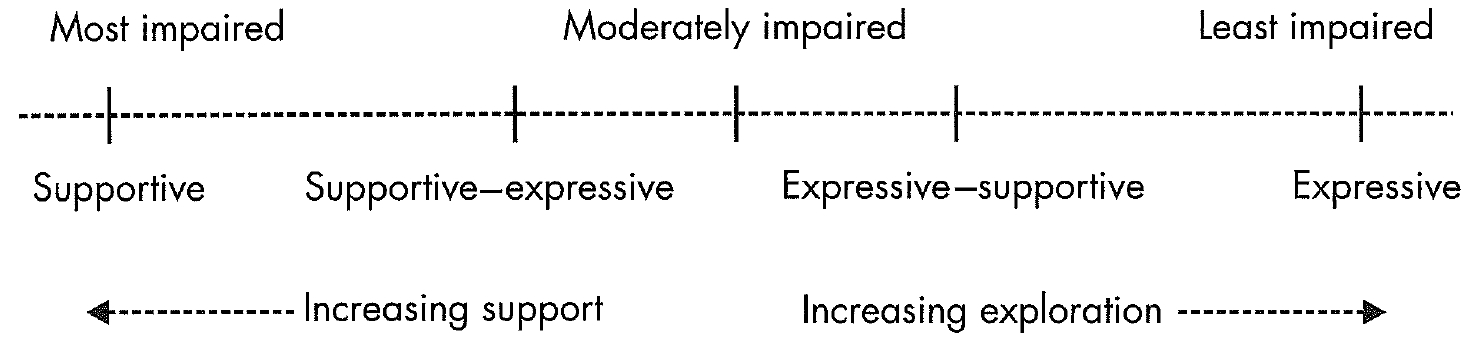

Human beings are endowed with complex psychological structures and, as a group, function along a sickness-health continuum according to their level of psychopathology, adaptive capacity, self-concept, and ability to relate to others (Figure 33-1; Winston et al. 2004). The continuum is conceptualized as extending from the most impaired patients to the most intact and well-put-together individuals. Impairments consist of behaviors that interfere with an individual's ability to function in everyday life, form relationships, think clearly and realistically, and behave in a relatively adaptive and mature fashion. Those individuals at the far right side of the continuum tend to function well, have good relationships, and lead productive lives and are able to enjoy a wide range of activities relatively free of conflict. In the middle of the continuum are people whose adaptation and behavior are uneven, so that they have significant problems in maintaining consistent functioning and stable relationships. An individual's position on the continuum can vary over time, depending on a number of factors. These factors include response to environmental stressors, physical illness, maturational growth, and psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy.

Placement of individuals on the continuum is associated with diagnosis. For example, patients with major mental disorders, pervasive developmental disorder, and severe borderline personality disorder generally lie on the left side of the psychopathology continuum. Limited intelligence and education may also place patients on the left side of the continuum. In meetings with this type of patient, the therapist focuses on the patient's daily activities, medications, and the use of resources for social rehabilitation. Patients with better adaptation are on the right side and include those individuals with Cluster C personality disorders (avoidant, dependent, obsessional), dysthymia, panic disorder, or adjustment disorders. In the middle of the continuum are individuals with conditions such as narcissistic personality disorder or non-psychotic depressions. Substance abuse problems occur across the continuum. Although diagnosis can provide a general idea of where a person might reside on the continuum, the actual placement will depend on the individual's level of psychopathology and adaptation.

Matching psychotherapy technique to patient locus on the psychopathology continuum is of crucial importance. Individual psychotherapies are conceptualized as a spectrum or continuum that extends from supportive psychotherapy to expressive or exploratory psychotherapy, as shown in Figure 33-1. From left to right, the psychotherapy continuum begins with supportive psychotherapy, traverses through supportive-expressive psychotherapy and expressive-supportive psychotherapy, and finally ends at expressive psychotherapy. Supportive psychotherapy uses supportive approaches, including cognitive-behavioral interventions, directed toward building psychological structure, stability, a sense of self, relationships, and self-esteem. Expressive psychotherapy is indicated for patients with relatively intact structures. Expressive psychotherapy explores relational and conflict issues, seeking personality change through analysis of the relationship between therapist and patient and through development of insight into previously unrecognized feelings, thoughts, and needs.

Figure 33-1. The psychopathology-psychotherapy continuum.

In practice, most individuals lie at neither end of the psychopathology continuum but instead have both conflict and structural problems. Many patients will require work in both areas, generally beginning with relationship problems and structure building and then perhaps going on to address conflict issues. Therefore, the psychotherapeutic approach will often be a combined supportive-expressive psychotherapy (Luborsky 1984).

As one approaches the midpoint of this spectrum, the distinctions become blurred and less well differentiated. And even the most exploratory and expressive forms of therapy include some supportive components and experiences; and supportive forms of psychotherapy may include an expansion of patients' awareness of their own mental processes, and thus involve elements of exploratory techniques. (Dewald 1994, p. 505)

The treatment of most patients involves supportive psychotherapy with some expressive elements, which should be used in a coherent, integrated fashion.

The most impaired patients require direct interventions aimed at improving ego functions, day-to-day coping, and self-esteem. Psychotherapy that is primarily expressive is contraindicated for these patients. The least impaired patients—those with good relationships who function well in everyday life—have traditionally been treated with expressive psychotherapy. However, more recent research and clinical papers indicate that patients respond equally well to supportive or expressive psychotherapy (Hellerstein et al. 1998) and that shifting to more expressive techniques should be done only when there are positive indicators for another approach.

Due to a paucity of data to support the assignment of patients to a given psychotherapy, supportive psychotherapy was previously described as the treatment for individuals not suitable for expressive psychotherapy. These individuals are the so-called difficult patients (Horowitz and Marmar 1985) who generally are not thought to be suitable for expressive psychotherapy and are not likely to be amenable to change (Winston et al. 1986). However, the Menninger psychotherapy study found that outcomes were similar for patients treated with supportive psychotherapy and patients treated with psychoanalysis or expressive psychotherapy (Wallerstein 1989). More recent studies (Hellerstein et al. 1998; Piper et al. 1998) have found that higher-functioning patients respond as well to supportive psychotherapy as to expressive therapy (see section "Efficacy Research" later in this chapter). These findings suggest that supportive psychotherapy can be used with a wide spectrum of problems and with higher-functioning patients. Luborsky (1984) developed a supportive-expressive psychotherapy that was used in numerous clinical trials for a wide variety of diagnoses and produced positive results.

In the past (Winston et al. 1986), supportive psychotherapy was generally considered the therapy of choice for patients on the left side of the sickness-health continuum, who have higher levels of psychopathology, chronic illness, and impaired adaptive skills. Generally, patients with severe and chronic illness cannot tolerate expressive psychotherapy, with its emphasis on exploration of feelings, interpersonal relationships, conflicts, and fantasies. These individuals have significant deficits in ego or psychological functioning (Table 33-2), including the following:

|

Table 33-2. Traditional selection criteria for impaired patients |

|

|

Poor reality testing Primitive and immature defenses Significantly impaired object and/or interpersonal relations Inadequate affect regulation Poor impulse control Overwhelming anxiety |

|

At the other end of the sickness-health continuum are relatively healthy individuals who have become symptomatic as a result of a severe and often overwhelming traumatic event. In other circumstances, persons in this group might be referred for expressive treatment, because they have good reality testing, high-level object/interpersonal relations with an ability to form a working alliance, a capacity to tolerate and contain affects and impulses, and a capacity for introspection (Table 33-3).

In crisis situations, supportive psychotherapy is usually delivered in an acute care or episode-of-care model. The following is an example of such a situation:

An otherwise healthy, well-compensated man lost his wife in an automobile accident and became depressed, with a negative attitude toward work and social relationships and diminished self-esteem. He entered into a supportive psychotherapy/crisis intervention that enabled him to begin a "normal" grieving process, ultimately recover his self-esteem, and begin to plan for changes in his life.

An acute crisis is not a diagnosis but rather a general syndromal description for patients whose customary coping skills and defenses have been overwhelmed by an often-unexpected event, resulting in intense anxiety and other symptoms (Dewald 1994). Crisis is the state that people experience when faced with actual or impending loss (see section "Crisis Intervention" later in this chapter). People in crisis may meet criteria for an adjustment disorder, which tends to be time limited. Supportive psychotherapy can help these patients to manage uncomfortable feeling states and enhance their coping strategies as this disorder resolves. The focus of the treatment is to reassure the patient that symptoms generally are time limited, to reduce stress by clarifying and providing information about what the patient is having difficulty adjusting to, and to support novel coping and problem-solving methods, including environmental change (Misch 2000).

|

Table 33-3. Traditional selection criteria for patients in crisis |

|

|

Relatively healthy and well functioning before crisis Good reality testing High-level object and/or interpersonal relations Ability to form working alliance Ability to tolerate and contain affects and impulses Capacity for introspection Good social supports |

|

Other indications for supportive psychotherapy include medical illness, substance use disorder, acute bereavement, and alexithymia. For a large number of medical conditions, supportive psychotherapy is the only treatment recommended. An understanding of an individual's defensive, cognitive, and interpersonal styles enables the therapist to assist the patient in developing better coping strategies (Bronheim et al. 1998). Supportive psychotherapy has been successfully used in patients with breast cancer (Classen et al. 2001), HIV-positive patients with depression (Markowitz et al. 1995), patients with pancreatic cancer (Alter 1996), cancer patients with depression (Massie and Holland 1990), patients with chronic pain (Thomas and Weiss 2000), patients with HIV-related neuropathic pain (Evans et al. 2003), and patients with somatization disorder (Quality Assurance Project 1985). In substance use disorders, the therapist focuses first on the development of a therapeutic alliance to enhance treatment retention and to create an environment within which the patient can begin cognitive and motivational work (O'Malley et al. 1992). In patients with poor ego strength, acute bereavement will overwhelm coping skills and produce symptoms such as self-reproach, social withdrawal, an inability to mourn, and depressive and anxiety symptoms (Horowitz et al. 1984). Supportive psychotherapy affords the patient an empathic holding environment in which the work of mourning can safely take place. In addition, healthy defenses are strengthened, concrete assistance for routine activities is offered when needed, and the patient is helped to avoid becoming socially withdrawn. Patients with alexithymia with severe restriction of affect, a seeming lack of capacity for introspection, an inability to articulate feeling states, and a diminished or absent fantasy life (Sifneos 1973) may become symptomatic in stressful situations. They tend to develop somatic preoccupations and become increasingly dysfunctional but are unable to communicate the effect of the stressful situation on their affective experience. Supportive psychotherapy, through directly working on somatic experiences and personal metaphors, can help the patient recognize, acknowledge, and identify emotions, thereby leading to an increased sense of mastery and self-esteem (Misch 2000).

There are few circumstances in which supportive psychotherapy is contraindicated (Frank 1975). It is contraindicated only when psychotherapy itself is contraindicated, such as in patients with de-liria, drug intoxication, late-stage dementia, malingering, or psychopathy, and in help-rejecting complainers.

CBT has been shown to be more effective than supportive psychotherapy for some conditions in a few studies. These disorders include panic disorder (Barlow and Craske 1989), obsessive-compulsive disorder (Foa and Franklin 2002), bulimia nervosa (Walsh et al. 1997), and posttrau-mqtic stress disorder (Foa 1997). However, as mentioned in the earlier section "Theory," supportive psychotherapy uses many of the techniques of CBT, and the two approaches can be successfully integrated (Winston and Winston 2002).

Supportive psychotherapy relies on direct measures rather than insight (Pin-sker 1997). A major tenet of traditional psychoanalytic psychotherapy was that unconscious conflict that produced the symptom or personality problem would become conscious, be explored, and be worked through. As a result, the symptom or personality problem would improve because it was no longer psychologically necessary. The working-through process involves exploring the patient's past history, particularly early relationships, to understand the genesis of the problems. In supportive psychotherapy, the therapist should understand many of the patient's dynamic issues and unconscious conflicts. However, conflicts generally are not explored with patients on the sicker side of the continuum. These patients are not able to contain or explore feelings and impulses and may become overwhelmed by anxiety. Instead, conscious problems and conflicts in the patient's current life are addressed (Table 33-4) (Dewald 1964/1971).

From the point of view of psychoanalytic theory, supportive psychotherapy supports the patient's defenses. When therapy is primarily expressive, defenses are challenged and explored so that underlying conflicts, wishes, and feelings that were being defended against become available for exploration and resolution. In supportive psychotherapy, defenses are questioned or confronted only when they are maladaptive and interfere with functioning. However, in practice, one does not work directly with a defense but rather works on the attitude or behavior it expresses (Winston et al. 2004). For example, the defense of projection can be harmful when a patient projects hostile feelings onto his boss and begins to argue with him. This problematic behavior at work needs to be addressed so that the patient does not lose his job.

|

Table 33-4. Strategies |

|

|

Strengthening and supporting defenses Maintaining and repairing the therapeutic relationship Promoting patient self-esteem Employing therapeutic self-disclosure and modeling Working primarily in the present |

|

The relationship between patient and therapist is a professional one, with the therapist providing a service that the patient needs. The therapist, as in all forms of psychotherapy, must maintain proper therapist-patient boundaries. The patient may need love or friendship, but the therapist does not become a lover or friend. The therapist does not advise the patient about what to invest in, how to vote, or where to vacation. These are products of his or her private, not professional, opinion. In traditional psychoanalytic psychotherapy, the therapist maintains neutrality and abstinence to further the exploratory process so that when the patient describes his or her perceptions or feelings about the therapist, these can be analyzed as products of projection onto the therapist of feelings the patient has about important figures in his or her past or current life. These projections onto the therapist are called transference. In supportive psychotherapy, the therapist is active and conversational, takes positions, answers questions, and self-discloses. The relationship between patient and therapist is supportive, providing security and safety for the patient. The therapist serves more as a model of identification rather than a transference figure (Winston et al. 2004), thus avoiding the chilling effect that abstinence can have on patients (Pinsker 1997). A positive patient-therapist relationship is always actively fostered by the therapist and is addressed and repaired when a misalliance develops (Winston and Winston 2002).

Self-disclosure by the therapist should have a therapeutic rationale—that is, be in the interest of the patient (Winston and Winston 2002). If self-disclosure is in the therapist's interest and takes the form of bragging, complaining, seductiveness, and so on, it is a boundary violation and exploitative. Simon (1988) observed that therapists' decisions about self-disclosure are generally related to modeling and educating, promoting the therapeutic alliance, validating reality and fostering the patient's sense of autonomy. Such disclosure enables patients with ego deficits to build a more stable and cohesive sense of self and other. Straightforward answers to personal questions from the patient can be given within appropriate social conventions of privacy and reticence. Selfdisclosure does have transference implications, but the therapist need not mention this to the patient (Winston and Winston 2002).

Improvement in self-esteem is an important goal of supportive psychotherapy. The therapist's positive regard, approval, acceptance, interest, respect, genuineness, and admiration help to further the patient's self-esteem. A patient who cannot form relationships with others finds in the therapist a person who is accepting and interested. The therapist communicates his or her interest in the patient by making it evident that he or she remembers their conversations and is aware of the patient's likes, dislikes, attitudes, and general sensibility. Acceptance is communicated by the avoidance of arguing, denigrating, and criticizing verbal interactions or therapist defensiveness.

The process of evaluation and case formulation is an essential element of all psychotherapeutic approaches. A central objective of the assessment process is to diagnose the patient's illness and describe the problems so that the patient can be treated appropriately. Another important objective of the evaluation process is to establish a therapeutic relationship that can further the patient's interest in and commitment to psychotherapy. A thorough evaluation should help the clinician to select the appropriate treatment approach. The treatment plan should be individualized to meet the patient's needs and goals.

The organizing treatment approach for each patient should be based on the central issues emerging from the assessment and case formulation. When a therapist meets a patient for the first time, the therapist generally does not know the extent of the patient's impairment, psychopathology, or strengths. Therefore, the initial interview should begin with the therapist's attempting to understand why the patient has come for treatment. All patients should have a thorough evaluation of both current problems and past history. At the end of the evaluation, the therapist should understand the patient's problems, interpersonal relationships, everyday functioning, and psychological or executive structure. The evaluation should not be simply a series of questions and answers but more of an exploration of the patient's life. The interview should be therapeutic, to help motivate the patient for treatment and promote the therapeutic alliance. The evaluation should promote the objectives of supportive psychotherapy: to ameliorate symptoms and to maintain, restore, or improve self-esteem, adaptive skills, and ego or psychological functions (Pinsker 1997). In a supportive approach, making an evaluation therapeutic generally involves the use of supportive psychotherapy interventions, such as praise, reassurance, encouragement, clarification, and confrontation (see Vignette 1, illustrating the assessment process, on the DVD that accompanies the book Learning Supportive Psychotherapy: An Illustrated Guide, by Winston et al. 2012).

Case formulation depends on an accurate and thorough assessment of the patient. The case formulation is an explanation of the patient's symptoms and psychosocial functioning. The therapist's formulation governs his or her interventions as well as which issues in the patient's life are selected for attention. Having a sense of the underlying issues at the start of treatment enhances the therapist's ability to respond empathically. At the same time, empathy for the patient helps the therapist to guide and plan therapy effectively. The initial formulation is tentative and must be modified as more is learned about the patient during the course of psychotherapy. The DSM diagnosis is an important part of case formulation but by no means the whole story. It does not illuminate an individual's adaptive or maladaptive characteristics or explain the unique life history of an individual.

The case formulation approaches described in the following subsections and listed in Table 33-5 (Winston et al. 2012) are derived from psychoanalytic (ego-interpersonal and relational psychology) and cognitive-behavioral (including learning theory) approaches. Supportive therapy uses elements of all these approaches but differs in how the elements are used. For example, a patient's underlying or hidden conflict may be clearly understood and formulated by the therapist but never or only partially explored in supportive psychotherapy. Although these case formulation approaches have always been described separately, a great deal of overlap exists, so the descriptions have some repetition.

A structural case formulation (Winston et al. 2012) attempts to capture the relatively fixed characteristics of an individual's personality, which is understood within a functional context (in contrast to dynamic and genetic approaches, which are more content based). The structural approach is also an assessment of psychopathology and enables the clinician, with some degree of accuracy, to place the patient on the psychopathology continuum. The major components of the structural approach are relation to reality, object relations, affect, impulse control, defenses, thought processes, and autonomous functions (perception, intention, intelligence, language, and motor development) and synthetic functions (ability to form a cohesive whole), as well as conscience, morals, and ideals.

The genetic approach to case formulation involves exploration of early development and life events that may help to explain an individual's current situation. Life presents many challenges, conflicts, and crises. These can be traumatic, depending on their severity, the developmental stage of the child, and the quality of his or her support system. An example of a persistent difficulty or traumatic situation is the experience of a young child growing up with a violent alcoholic father who is demeaning and at times physically abusive.

|

Table 33-5. Types of case formulation |

|

|

Structural Genetic Dynamic Cognitive-behavioral |

|

The dynamic approach concerns mental and/or emotional tensions that may be conscious or unconscious. The approach focuses on conflicting wishes, needs, or feelings and on their meanings. It focuses on current conflicts, whereas the genetic approach highlights a person's childhood traumas and conflicts and their possible meanings. In supportive psychotherapy, the most important strategic approach is the structural (and to some extent, the dynamic) formulation, because mapping out current areas of difficulty and ameliorating them are more important than understanding the genetic basis or cause of the difficulty (Winston et al. 2004).

The cognitive-behavioral approach addresses an individual's underlying psychological structure and the content of his or her thoughts (Winston et al. 2012). The cognitive-behavioral case formulation model has been described by Tomkins (1996) as encompassing a number of components, including the problem list, followed by core beliefs, origins, precipitants, and predicted obstacles to treatment. (For a more complete description of CBT, see Chapter 32, "Cognitive-Behavior Therapy.")

A well-thought-out and comprehensive treatment plan should emerge from the case formulation (Winston et al. 2004, 2012). Generally, this plan will include treatment goals, the types of interventions to be used, and the frequency of sessions. In supportive psychotherapy, the frequency of visits should be flexible, depending on the patient's needs. In crisis situations, patients may be seen frequently, whereas more stable patients may be seen less often. However, setting a specific repeated time to meet tends to reduce anxiety, which is an important objective of supportive psychotherapy.

For patients requiring supportive psychotherapy, organizing goals, as stated by most authors, are amelioration of symptoms and improvement and enhancement of adaptation, self-esteem, and overall functioning (Table 33-6) (Dewald 1994; Winston et al. 2004, 2012). These goals are quite different from the goals of expressive psychotherapy but similar to those of CBT. In expressive psychotherapy, the goals are both symptom and personality change through analysis of the patient-therapist relationship and development of insight into previously unrecognized feelings, thoughts, needs, and conflicts.

Until recently, it has been assumed that long-term changes in symptoms, self-esteem, conflicts, and adaptation cannot occur in supportive psychotherapy because this type of therapy does not aim at change in personality or ego structure. However, more recent studies have suggested that supportive psychotherapy can produce personality change in patients on the healthier side of the sickness-health continuum (Winston et al. 2001).

|

Table 33-6. Goals |

|

|

Ameliorate symptoms Improve adaptation Enhance self-esteem Improve functioning |

|

Setting treatment goals in psychotherapy is important in guiding the treatment, because both therapist and patient must agree on the objectives of treatment. The goals set within the first few sessions should be viewed as preliminary and open to change. Both immediate objectives for each session and ultimate goals for treatment should be considered (Parl-off 1967). An example of an immediate goal for a patient who has temporarily left work would be to return to work within a week or so. An ultimate goal would be to promote job stability and improve relationships with coworkers.

Clearly outlined goals help motivate patients and promote the therapeutic alliance as patient and therapist work toward a common end. The goals of therapy should generally be the patient's and should be realistic. In the event of disagreement on goals, the therapist enters into an exploration of the problem. For example, many patients with chronic psychiatric illness often discontinue their medications. In these cases, a major goal of treatment is to help patients remain on medications. Therefore, exploring the reasons for discontinuation and educating patients about the risks of discontinuing are in order.

Finally, treatment goals should never be regarded as fixed and unchangeable. If a patient improves, goals can be expanded or changed.

Supportive psychotherapy depends on clearly defined techniques designed to achieve the goals of maintaining or improving the patient's self-esteem, psychological (ego) functioning, and adaptation to the environment (Pinsker 1997). In supportive treatment, the objectives include reduction of anxiety, promotion of stability, and relief of symptoms. These goals are accomplished by working in the here and now rather than in the past. The therapeutic relationship becomes a focus in a real as opposed to a transferential manner. Generally, resistance is not addressed, and adaptive defenses are strengthened and supported (Winston and Winston 2002). Table 33-7 presents a list of interventions used in supportive-expressive psychotherapy. Learning theory interventions are discussed separately in a later section of the chapter.

The style of communication in supportive psychotherapy tends to be more conversational than in expressive psychotherapy (Winston et al. 2004, 2012). Silences are avoided because they can raise the individual's level of anxiety. There is a give-and-take exchange, and challenging questions are not asked. Questions beginning with "why" are avoided because they can increase anxiety and threaten self-esteem (Pinsker 1997).

Praise, reassurance, and encouragement are considered useful techniques for promoting patient self-esteem, especially if the therapist is genuine when using these techniques (Lewis 1978). Patients quickly pick up on comments that are patronizing or gratuitous and may feel misunderstood. Praise, when offered, tends to be reality based and to support more adaptive behaviors. Examples of praise include "It's good that you can be so considerate of other people" or "It's terrific that you got yourself to go to that lecture."

|

Table 33-7. Interventions |

|

|

Conversational style Praise, reassurance, and encouragement Advice Rationalizing and reframing Rehearsal or anticipatory guidance Confrontation, clarification, and interpretation |

|

Words spoken in an attempt to reassure a patient must not be empty or without basis, and the patient must believe that the reassurance is based on an understanding of his or her unique situation. Furthermore, the therapist must limit reassurance to areas in which he or she has expert knowledge or dependable common information (Winston et al. 2004). Many patients ask their therapist if they will get better. A response of "Yes, you will get better" may be misleading and false. A more appropriate response would be "Most people with your condition improve."

Encouragement has a major role in general medicine and rehabilitation. Patients with chronic schizophrenia, depression, or a passive-dependent style are often inactive, mentally and physically. The psychiatrist encourages the patient to maintain hygiene, to get exercise, to interact with other people, sometimes to be more independent, and sometimes to accept the care and concern of others. It is useful to think about encouragement as a form of coaching to help patients engage in different behaviors and activities (Pinsker 1997). For example, a patient complained that she was inept because she was unable to write a cover letter for a job application. The therapist said, "You just need to get started. Let's see what we can do now to help you get started."

Advice is an important tactic of supportive psychotherapy and should be based on the therapist's knowledge and expertise in the field of psychiatry. Although early psychoanalytic authorities disparaged giving advice, Sullivan (1971) pointed out that the value of advice giving is often underrated. In contrast to the more abstinent therapeutic stance employed in expressive psychotherapy, the therapist conducting supportive psychotherapy can be direct and take an active role with patients. Teaching and advice generally go hand in hand. In the supportive psychotherapy literature, the term lending ego has been used to convey that the therapist models reasonable, controlled behavior in addition to teaching about it. The therapist gives advice about or teaches about the supportive psychotherapy objectives of improving ego functions or adaptive skills, as in the following example: "You tend to put up with things until you become furious, as you did with your friend who always keeps you waiting; then you lose it and scream at people. Dealing with the problem earlier, before it becomes so upsetting and extreme, is usually a better approach." When a therapist is telephoned by a patient who becomes disorganized in response to minimal stress, the therapist tells her to first get dressed, then have breakfast, and then straighten up the house; here the therapist is not giving advice but rather providing help with routine, helping provide structure, and possibly encouraging the use of compulsive defenses.

Rationalizing and reframing provide the patient with an alternative way of looking at an event that was previously perceived as painful or negative. The challenge in using rationalization and reframing is to avoid sounding fatuous or arguing with and contradicting a patient. An example is that of a young mother who complained that her toddler had started to run away from her and expressed her belief that the child was losing interest in her. The therapist might reframe this painful and negative perception by saying, "She feels secure enough with you that she's free to explore the world."

Rehearsal or anticipatory guidance is a technique that is as useful in supportive psychotherapy as in CBT. Anticipatory guidance is a useful technique for helping patients prepare for future encounters with situations perceived as potentially problematic. Preparation for a difficult event can be likened to studying for an examination or rehearsing for a performance. The objective is to consider in advance what the obstacles might be to a proposed course of action and then to prepare strategies for dealing with them. Gaining mastery over an anticipated situation diminishes anxiety and enhances self-esteem. An example of anticipatory guidance would be taking a patient through an initial phone call to a prospective employer. The patient expects a cold reception and rejection. Rehearsal provides the patient with a number of scenarios and responses so that he or she will be equipped to cope with the anxiety engendered by making the phone call and will have a repertoire of responses ready.

Confrontation addresses a patient's defensive behavior by bringing to the patient's attention a pattern of behaviors, ideas, or feelings he or she has not recognized or has avoided. In supportive psychotherapy, confrontations generally are empathically framed and are used to address maladaptive defenses; adaptive defenses are encouraged. Confrontation in a supportive mode is illustrated in the following dialogue:

Patient: I went to my parents' home to speak with them about borrowing some money to pay for several unexpected bills that I have to pay, but I got into a silly argument with them and never had a chance to ask them.

Therapist: We know that it's hard for you to ask them for anything, so could it be that you got into the argument with them to avoid asking them for money?

Clarification is summarizing, paraphrasing, or organizing without elaboration or inference. It is central to the style of communication between patient and therapist and is the most frequently used intervention in supportive-expressive psychotherapy. It demonstrates that the therapist is attentive and is processing what he or she hears. Clarification frames a communication so that both parties agree on what is being discussed. Summarizing and restating help organize the patient's thinking and provide structure. In the following example, the therapist clarifies through summarizing:

Patient: I can't seem to concentrate on anything. My house is costing too much, so I have to sell it, but I have to fix some things in it first ... I can't seem to get started. Collection agencies are after me, and my ex-wife keeps calling about child support—and now my car got hit, so I can't use it.

Therapist: It sounds like a lot of things are troubling you, and you're experiencing being overwhelmed. Let's examine these things one at a time and see what we can come up with.

An interpretation is an explanation that brings meaning to the patient's behavior or thinking (Othmer and Othmer 1994). Generally, it makes the individual aware of something that was not previously conscious (Greenson 1967). An interpretation can link thoughts, feelings, and behaviors toward people in the patient's current life to people from the past and/or to the therapist. In supportive psychotherapy, interpretation is generally more limited in scope. Present rather than past relationships are emphasized; affects and impulses are rarely interpreted. Incomplete or inexact interpretations (Glover 1931) offer explanations that are plausible and help the patient make sense of his or her experience but do not contain material that might disturb the patient.

A major approach to facilitate learning is effective processing (deWinstanley and Bjork 2002), which includes interpretation, elaboration, generation, and interleaving. Processing involves interpretation that is focused and accurate, accompanied by thorough elaboration. Information that can be interpreted (linked) through associations with preexisting knowledge will be easier to learn than information that is not interpreted. It is important to note that interpretation as a technique of learning theory is not the classical technique of interpretation in dynamic psychotherapy but more of a linkage to preexisting knowledge. Elaborative ■processing has to do with information being thought of in a number of different ways and connected with other previously known information. Generation (Richland et al. 2005) is the producing of information during learning rather than having that information presented by a teacher or therapist. Interleaving (Richland et al. 2005) is the learning of two or more sets of information such that instruction and focus alternate between the sets. This is in contrast to learning in which each set is focused on separately. In supportive psychotherapy the therapist promotes use of these processing techniques by asking questions designed to help patients think about their problems in a number of different ways and not supplying the answers. The patient is encouraged to process information in collaboration with the therapist.

Critical reflection (Mezirow 1998) is an important technique of learning theory. It is the process by which a person questions and then replaces or reframes an assumption and the process through which alternative perspectives are formed on ideas, actions, and forms of reasoning previously taken for granted. Supportive psychotherapy and other psychotherapy approaches use reframing and attempt to provide patients with alternative ways of thinking about the world, relating to others, and solving problems.

The components of the therapeutic relationship are considered to be the transference-countertransference configuration, the real relationship, and the therapeutic alliance (Greenson 1967). Although these three components are intimately related and form a cohesive whole, discussion of each component separately provides more clarity. Transference and real relationship issues play a role in every transaction within the therapeutic relationship. At certain times transference aspects maybe more important, whereas at other times real relationship issues may predominate. From this point of view, a continuum exists between transference issues and real issues that corresponds to the supportive-expressive psychotherapy continuum. Expressive therapy places more emphasis on the transference, whereas supportive psychotherapy focuses more on the real relationship.

Pinsker (1997) and others (e.g., Misch 2000) have described general principles that address the relationship of supportive psychotherapy and the therapeutic relationship. These principles are listed in Table 33-8.

Classically, transference has been described as a special type of object relationship consisting of behaviors, thoughts, feelings, wishes, and attitudes directed at the therapist that are related to important people in the patient's past. Most commonly displaced onto the therapist are attitudes toward significant people such as parents, siblings, grandparents, or teachers. Essentially, the past is revived in the present. The real relationship underlies all psychotherapy. It exists in the here and now of the therapeutic interaction between patient and therapist, encompassing a genuine mutual liking for each other that is authentic, trusting, and realistic, without the distortions that are characteristic of transference (Greenson 1967). The real relationship includes the patient's hopes and aspirations for help, care, understanding, and love, as well as the everyday interactions that take place on a social level between individuals.

|

Table 33-8. The patient-therapist relationship |

|

|

Positive feelings and thoughts about the therapist are generally not focused upon in order to maintain the therapeutic alliance. The therapist is alert to distancing and negative patient behaviors, so as to anticipate and avoid a disruption in treatment. When a patient-therapist problem is not resolved through practical discussion, the therapist moves to discussion of the therapeutic relationship. The therapist attempts to modify the patient's distorted perceptions using clarification and confrontation but usually not interpretation. If indirect means fail to address negative transference or therapeutic impasses, explicit discussion about the therapeutic relationship may be warranted. The therapist uses only the amount of expressive technique necessary to address negative issues in the patient-therapist relationship. A positive therapeutic alliance may allow the patient to listen to the therapist present material that the patient would not accept from anyone else. When making a statement that the patient might experience as criticism, the therapist may have to frame the statement in a supportive, empathic manner or first offer anticipatory guidance. |

|

In psychotherapy at the supportive end of the psychotherapy continuum, transference can be used to guide therapeutic interventions. However, transference is not generally discussed unless negative transference threatens to disrupt treatment. Positive transference reactions generally are not explored but rather are simply accepted. Negative reactions must always be investigated, however, because they may compromise the treatment (Winston and Winston 2002). The real relationship is paramount and based on overt mutuality in the conduct of therapy.

In expressive psychotherapy, both positive and negative transference phenomena are of pivotal importance for identifying intrapsychic conflict; therapeutic gain is ascribed to the emotional working-through of these relationships. Transference clarification and interpretation are important interventions. The real relationship serves as more of a backdrop, and the emphasis is on the transference.

Therefore, transference is increasingly worked with as one moves across the psychotherapy continuum from supportive to expressive psychotherapy, whereas the emphasis on the real relationship increases as one moves from expressive to supportive psychotherapy. In the middle of the continuum, where most psychotherapy takes place, a mixture of supportive and expressive approaches to transference takes place. In supportive psychotherapy, the therapist clarifies often, confronts at intervals, and interprets infrequently. The therapist's interventions help the patient recognize and address maladaptive behavior and cognitive problems that are reflected in behavior with the therapist and are illustrative of the patient's behavior with others. The goal of these interventions is in keeping with the goals of supportive psychotherapy: to increase self-esteem and adaptive functioning.

The following example illustrates some of the strategies employed to address positive transference reactions. John, age 54 years, tells his therapist how much his relationship with his wife has improved since he started therapy. He attributes this to the therapist's interest in him. In supportive psychotherapy, the therapist would not explore this but would accept the compliment, conceptualizing John's statement as a reflection of the real relationship, and might say, "I'm glad to be of help to you." This opportunity also might be used to bolster the patient's self-esteem by adding, "Our work has been a joint effort, so you have to take some of the credit, too."

Classically, countertransference is the therapist's transference to the patient (Green-son 1967). It includes behaviors, thoughts, wishes, attitudes, and conflicts derived from the therapist's past and displaced onto the patient. A broader definition includes the real relationship, consisting of reactions most people would have to the patient, determined by moment-to-moment interactions in the therapeutic relationship, which is a transactional construct affected by what the therapist brings to the situation as well as by what the patient projects (Gabbard 2001; Winston and Winston 2002). The therapist's countertransference reactions can lead to misunderstanding of the patient and can result in inappropriate behavior toward the patient. Countertransference reactions can also be a powerful tool for understanding and empathizing with the patient (Gabbard 2001). To accomplish this, the therapist must monitor his or her own feelings toward the patient to help gain access to the patient's inner world and unconscious.

The use of empathy is important in facilitating, impeding, or distorting countertransference awareness. Empathy can be defined as "feeling oneself into" something or someone (Wolf 1983). Therefore empathy is a method of gathering data about the mental life of another person. The ability to empathize by accurately sensing and understanding what a person is experiencing will enable the therapist to attend to countertransference reactions. The following is an example of the use of countertransference in supportive psychotherapy:

A middle-aged man began to describe how people at work tended to avoid him, even when he thought he was being friendly. The therapist responded empathically by remarking, "That must be hard for you." The patient reacted in an angry manner. The therapist responded by saying, "I'm finding my temperature rising with your criticisms of me, and I can't help wondering if you get your coworkers feeling the same way. However, I won't act on my feelings the way they do. I'll continue to sit and talk with you; I won't make excuses and leave."

From the vantage point of interpersonal communication theory, Kiesler (2001) described effective feedback of countertransference feelings as applying the principle that disclosing metaphors of fantasies has the least threatening effect compared with disclosing direct feelings or tendencies toward action. This principle is highly consistent with supportive psychotherapy approaches, in which it is safer, more respectful, and more protective of the therapeutic alliance to say "I'm finding my temperature rising" rather than "I'm very angry with you." The therapist's modulated expression of countertransference feeling not only offers disconfirmation of the patient's maladaptive construal style but also models adult restraint and containment, not denial of affect. The therapist who responds to the patient's hostility in a complementarily hostile manner is arguing. Arguing not only is poor technique but also is predictive of poor outcome (Henry et al. 1990).

The therapeutic alliance is a component of the real relationship and forms an essential part of the foundation upon which all psychotherapy stands. Zetzel (1956) first used the term therapeutic alliance for the "unobjectionable positive transference" that was seen as an essential element in the success of psychotherapy. She believed that the capacity to form an alliance is based on an individual's early experiences with the primary caregiver. In the absence of this capacity, the task of the therapist, early in treatment, is to provide a supportive relationship to foster development of a therapeutic relationship.

Greenson (1967) emphasized the collaborative nature of the alliance, in which the patient and therapist work together to promote therapeutic change. Bordin (1979) operationalized the therapeutic alliance concept as the degree of agreement between patient and therapist concerning the tasks and goals of psychotherapy and the quality of the bond between them. He conceptualized the alliance as evolving and changing as the result of a dynamic interactive process occurring between patient and therapist. Outcome research in psychotherapy supports the idea that the quality of the therapeutic alliance is the best predictor of treatment outcome (Horvath and Symonds 1991). There is evidence that in brief supportive and supportive-expressive psychotherapies, an early and strong therapeutic alliance is predictive of positive outcome (Hellerstein et al. 1998; Luborsky 1984).

The therapeutic alliance is most likely the therapeutic foundation for change in supportive psychotherapy rather than the vehicle for change as in more expressive psychotherapies (Hellerstein et al. 1998; Horvath and Symonds 1991). Therefore, the therapist fosters the alliance through active measures, acting as a good parental role model by being tolerant and non-judgmental (Misch 2000). Direct measures that support the self-esteem of the patient support the therapeutic alliance.

The stability of the therapeutic alliance appears to be related to the psychotherapy continuum. On the supportive psychotherapy side of the continuum, compared with the expressive end, the alliance tends to be more stable because it is not threatened by challenging confrontations or interpretations that may heighten patient anxiety (Hellerstein et al. 1998).

Patients vary in their capacity to establish a positive alliance with a therapist. Those on the sickness side of the psychopathology continuum, who have structural deficits, especially in object relations, may have problems developing a positive relationship with the therapist. The inability to establish "basic trust" (Erikson 1950) interferes with the establishment of a therapeutic bond. With these patients, a major therapeutic task, especially early in treatment, is building a trusting relationship.

Breaks in the therapeutic alliance are not unusual (Safran et al.1994; Winston and Muran 1996). In fact, misunderstandings between therapist and patient occur for a number of reasons. Over the course of psychotherapy, the patient may at various times experience the therapist as critical, insensitive, distant, withholding, untrustworthy, intrusive, unempathic, and so on, any of which will contribute to a misalliance.

In supportive psychotherapy there is ample opportunity and breadth of strategy to intervene effectively when problems in the alliance occur. Less constraint is placed on the therapist about communicating his or her sincere regret at having unwittingly impugned or patronized the patient or having raised a subject that the patient found intrusive, anxiety provoking, or simply unpalatable. Generally, when the therapist anticipates or notices a misalliance, supportive techniques are used as the first line of repair (Bond et al. 1998). The therapist attempts to address the problem in a practical manner, staying within the current situation, before moving to symbolic or transference issues. The following is an example of a problem in this area:

A patient in supportive psychotherapy who regularly kept appointments failed to appear at a session. The therapist did not attempt to contact the patient. In the next session, the patient began by angrily asking the therapist why there had been no attempt to contact her. The patient explained that she had been ill and taken to the hospital.

In any psychotherapy, but particularly in supportive treatment, the patient should have been called. Doing so would have conveyed respect for and interest in the patient and prevented a rupture in the alliance. However, once the misalliance has occurred, the therapist must quickly move to repair the alliance by encouraging the patient to express her feelings about not being called and then acknowledging and accepting her criticism as well as offering an apology.

The psychiatric disorders on the sickness side of the psychopathology continuum for which supportive psychotherapy is indicated include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe personality disorders, substance use disorder, and co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders. All of these disorders may benefit from specialized approaches integrated into a supportive psychotherapy framework that is combined with cognitive-behavioral techniques. A full discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this chapter. Therefore, only a brief summary of this work, using two disorders as illustrations, is presented here. For a more comprehensive review, the reader is directed to Chapter 8, "Applicability to Special Populations,' in the book Learning Supportive Psychotherapy: An Illustrated Guide (Winston et al. 2012).

For individuals with severe impairments, such as patients with schizophrenia, a broader approach of social skills training (Benton and Schroeder 1990) and psychoeducation (Goldman and Quinn 1988) is indicated. Combining these approaches with supportive psychotherapy would include providing education about the illness, facilitating reality testing, promoting medication compliance, helping the patient with problem solving, and reinforcing adaptive behaviors with praise (Lamberti and Herz 1995). In addition, the therapist uses supportive techniques such as behavioral goal setting, encouragement, modeling, shaping, and praise to teach interpersonal skills. Studies have demonstrated the utility of these interventions in improving social competence (Heinssen et al. 2000).

Patients with substance use disorders can benefit from supportive psychotherapy, which can help them develop coping strategies to control or reduce substance use and diminish anxiety and dysphoria. The therapist must actively strive to maintain a positive therapeutic alliance so that the patient can remain in treatment and actively contribute to the work of therapy. Newer evidence-based strategies such as psychoeducation, relapse prevention (Marlatt and Gordon 1985), and motivational interviewing (Rollnick and Miller 1995) should be integrated into supportive psychotherapy, along with twelve-step programs and group psychotherapy.

Crisis intervention approaches began during World War II, when soldiers with traumatic stress disorders were treated at or near the front lines with crisis intervention techniques and quickly returned to their combat units (Glass 1954). At about the same time, Lindemann (1944) began working with survivors and relatives of survivors of the Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire in Boston. These individuals experienced acute grief and were unable to cope with their bereavement. In his seminal article, Lindemann (1944) described normal and morbid grief and contrasted the two. The survivors and their families were helped to do the necessary "grief work," which involved going through the mourning process and experiencing the loss.

Parad and Parad (1990) defined crisis as an "upset in a steady state, a turning point leading to better or worse, a disruption or breakdown in a person's or family's normal or usual pattern of functioning" (pp. 3-4). A crisis occurs when an individual encounters a situation that leads to a breakdown in functioning, creating disequilibrium. Generally, a crisis is precipitated by a hazardous event or stressor, such as a catastrophe or disaster (e.g., earthquake, fire, war, terrorist act), a relationship rupture or loss, rape, or abuse. A crisis may also result from a series of difficult events or mishaps rather than from one major occurrence. During crises, individuals perceive their lives, needs, security, relationships, and sense of well-being to be at risk. An individual's reaction to stress is the result of a number of factors, including age, health, personality issues, prior experience with stressful events, support and belief systems, and underlying biological or genetic vulnerability. Crises tend to be time limited, generally lasting no more than a few months; the duration depends on the stressor and on the individual's perception of and response to the stressor.

Crisis intervention is a therapeutic process aimed at restoring homeostatic balance and diminishing vulnerability to the stressor (Parad and Parad 1990; Winston et al. 2004, 2012). Homeostasis is accomplished by the therapist's helping to mobilize the individual's abilities and social network and to promote adaptive coping mechanisms to reestablish equilibrium. Crisis intervention is a short-term approach that focuses on solving the immediate problem and includes the entire therapeutic repertoire for helping patients deal with the challenges and threats of overwhelming stress (Table 33-9).

The distinction between crisis intervention and psychotherapy is often blurred because the two approaches may overlap with regard to technique and length of treatment. Crisis intervention is generally expected to involve one to three sessions, whereas the duration of brief psychotherapy can extend from a few visits to 20 or more sessions. However, in the 1990s, crisis intervention began to include treatments lasting longer than just a few sessions (Parad and Parad 1990). This more inclusive form of crisis therapy is based on a number of different treatments, including supportive-expressive, cognitive-behavioral, humanistic, family, and systems approaches, as well as the use of medication when indicated (Winston et al. 2012). Systems approaches can be broad and can encompass actions such as working with and referral to social service agencies, mobile crisis units, suicide hotlines, and law enforcement agencies. An additional focus of crisis intervention has been on emergency management and prevention through the use of various forms of debriefing (Everly and Mitchell 1999).

|

Table 33-9. Crisis interventions |

|

|

Crisis—a situation that can lead to a breakdown in functioning, creating disequilibrium Crisis intervention—a brief therapeutic process aimed at restoring homeostatic balance and promoting adaptive coping mechanisms |

|

A thorough evaluation of a patient in crisis, including an ego assessment (Cap-lan 1961), is critical. The evaluation consists of assessing the individual's capacity to deal with stress, maintain ego structure and equilibrium, and deal with reality, as well as assessing the person's problem-solving and coping abilities. The evaluation session should be therapeutic as well as diagnostic because the patient is in crisis and is seeking relief from suffering. (See Vignette 5 on the evaluation process in crisis intervention from the book Learning Supportive Psychotherapy: An Illustrated Guide by Winston et al. 2012.)

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors are so common in patients in crisis that it is essential to ask patients about suicidal ideas and attempts. A careful and thorough assessment of the suicidal patient is critical to determine the diagnosis and the proper treatment approach. Crisis intervention approaches, generally accompanied by the use of medication, often play an important role in the treatment of suicidal individuals (Winston et al. 2012).

Treatment approaches used in crisis intervention vary depending on the needs of each patient but generally include supportive interventions, exposure therapy, and cognitive restructuring. Therapists must pay particular attention to establishing and maintaining a positive therapeutic alliance. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, in New York City and Washington, D.C., have made the general public and mental health professionals more aware of these issues and of the need for crisis intervention services. (See Vignette 5, illustrating crisis intervention therapy for a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder secondary to the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, on the DVD that accompanies the book Learning Supportive Psychotherapy: An Illustrated Guide by Winston et al. 2012.)

A limited number of controlled clinical trials of supportive psychotherapy have been reported. However, some early uncontrolled studies and more recent controlled trials generally support the efficacy of supportive psychotherapy for a number of psychiatric disorders. This chapter does not present a review of efficacy research in supportive psychotherapy. Such a review is provided by Winston et al. (2012; see "Suggested Readings" list at the end of this chapter).

It is essential for clinical psychiatrists to have a working knowledge of supportive psychotherapy because it is the most commonly employed psychotherapy. In all forms of psychiatric practice—outpatient, inpatient, consultation-liaison, medication management, and so on—the strategies and techniques of supportive psychotherapy are invaluable. Every psychiatrist should be able to perform a thorough patient evaluation and diagnostic interview and be able to formulate a comprehensive treatment plan that can encompass a variety of possible approaches, including psychopharmacological and psychosocial treatments. In addition, psychiatrists should have an understanding of the therapeutic relationship and how to establish a therapeutic alliance. Concepts such as transference and countertransference, defenses, adaptive styles, and self-esteem issues all need to be understood and worked with in an effective manner.

Psychiatrists engaged primarily in the practice of psychopharmacology should have a good working knowledge of supportive psychotherapy, because this is the approach that seems to be effective with most patients and uses psychoeducation in a major way. Psychoeducation involves imparting information to patients, in a give-and-take manner, about psychiatric disorders, medication actions and side effects, interpersonal and family issues, and problems of everyday living.

Unfortunately, supportive psychotherapy has not been taught in any kind of systematic fashion in residency training programs. However, the requirements of the Residency Review Committee for

Psychiatry now mandate that psychiatry residents must be certified as competent by their training programs in three types of psychotherapy, one of which is supportive psychotherapy (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 2007). These new requirements may help to foster the teaching and supervision of supportive psychotherapy in residency training programs.

Supportive psychotherapy is a broad-based treatment that is effective for many different types of patients and psychiatric disorders. Despite being the most widely used psychotherapy, it remains undervalued and is rarely taught in a systematic fashion. However, this appears to be changing because of the requirements for the teaching of supportive psychotherapy in residency training programs. It is clear that more research in supportive psychotherapy is needed to help define and distinguish which strategies and techniques are useful with what type of patient. In addition, the field needs to develop a better understanding of the mechanism of change and a more comprehensive and integrated theoretical foundation for supportive psychotherapy.

Key Clinical Points

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Psychiatry. July 2007. Available at: www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/400pr07012007.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2010.

Alter CL: Palliative and supportive care of patients with pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol 23:229-240, 1996

Aron L: Meeting of Minds. Hillsdale, NJ, Analytic Press, 1996

Barlow D, Craske M: Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic. Albany, NY, Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders, State University of New York, 1989

Benton MK, Schroeder HE: Social skills training with schizophrenics: a meta-analytic evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol 58:741-747, 1990

Bond M, Banon E, Grenier M: Differential effects of interventions on the therapeutic alliance with patients with personality disorders. J Psychother Pract Res 7:301-318, 1998

Bordin ES: The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice 16:252-260, 1979

Bowlby J: A Secure Base. New York, Basic Books, 1988

Bronheim HE, Fulop G, Kunkel EJ, et al: The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine practice guidelines for psychiatric consultation in the general medical setting. Psychosomatics 39(4):S8-S30, 1998

Caplan G: An Approach to Community Mental Health. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1961

Classen C, Butler LD, Koopman C, et al: Supportive expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized clinical intervention trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:494-501, 2001

Dewald PA: Psychotherapy: A Dynamic Approach (1964). New York, Basic Books, 1971

Dewald PA: Principles of supportive psychotherapy. Am J Psychother 48:505-518, 1994

deWinstanley PA, Bjork RA: Successful lecturing: presenting information in ways that engage effective processing, in Applying the Science of Learning to University Teaching and Beyond (New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No 89). Edited by Halpern DF, Hakel MD. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass, 2002, pp 19-31

Erikson EH: Childhood and Society. New York, WW Norton, 1950

Etkin A, Pittenger C, Polan HJ, et al: Toward a neurobiology of psychotherapy: basic science and clinical applications. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 17:145-158, 2005

Evans S, Fishman B, Spielman L, et al: Randomized trial of cognitive behavior therapy versus supportive psychotherapy for HIV-related peripheral neuropathic pain. Psychosomatics 44:44-50, 2003

Everly GS Jr, Mitchell JT: Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM): A New Era and Standard of Care in Crisis Intervention, 2nd Edition. Ellicott City, MD, Chevron, 1999

Fairbairn WRD: An Object-Relations Theory of the Personality. New York, Basic Books, 1952

Foa EB: Trauma and women: course, predictors, and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 58:25-28, 1997

Foa EB, Franklin ME: Psychotherapies for obsessive compulsive disorder: a review, in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, 2nd Edition. Edited by Maj M, Sartorius N, Okasha A, et al. Chichester, UK, Wiley, 2002, pp 93-115

Frank JD: General psychotherapy: the restoration of morale, in American Handbook of Psychiatry, 2nd Edition, Vol 5: Treatment. Edited by Freedman DX, Dyrud JE. New York, Basic Books, 1975, pp 117-132

Freud S: Lines of advance in psycho-analytic therapy (1919), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol 17. Edited by Strachey J. London, Hogarth, 1955, pp 157-168

Gabbard GO: A contemporary psychoanalytic model of countertransference. J Clin Psychol 57:983-991, 2001

Glass A: Psychotherapy in the combat zone. Am J Psychiatry 110:725-731, 1954

Glover E: The therapeutic effect of inexact interpretation: a contribution to the theory of suggestion. Int J Psychoanal 12:397-411, 1931

Goldman CR, Quinn FL: Effects of a patient education program in the treatment of schizophrenia. Hosp Community Psychiatry 39:282-286, 1988

Greenson RR: The Technique and Practice of Psychoanalysis. New York, International Universities Press, 1967

Hartmann H: Ego Psychology and the Problem of Adaptation (1939). Translated by Rapaport D. New York, International Universities Press, 1958

Heinssen RK, Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Psychosocial skills training for schizophrenia: lessons from the laboratory. Schizophr Bull 26:21-46, 2000

Hellerstein DJ, Rosenthal RN, Pinsker H, et al: A randomized prospective study comparing supportive and dynamic therapies: outcome and alliance. J Psychother Pract Res 7:261-271, 1998

Henry WP, Schacht TE, Strupp HH: Patient and therapist introject, interpersonal process, and differential psychotherapy outcome. J Consult Clin Psychol 58:768-774, 1990

Horowitz MJ, Marmar C: The therapeutic alliance with difficult patients, in Psychiatry Update: The American Psychiatric Association Annual Review, Vol 4. Edited by Hales RE, Frances AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1985, pp 573-585

Horowitz MJ, Marmar C, Weiss DS, et al: Brief psychotherapy of bereavement reactions: the relationship of process to outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 41:438-448, 1984

Horvath AO, Symonds BD: Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol 38:139-149, 1991

Kiesler HD: Therapist counter transference: in search of common themes and empirical referents. J Clin Psychol 57:1053-1063, 2001

Kohut H: The Analysis of the Self. New York, International Universities Press, 1971

Lamberti JS, Herz MI: Psychotherapy, social skills training, and vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia, in Contemporary Issues in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Edited by Shriqui CL, Nasrallah HA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 713-734

Lewis J: To Be a Therapist: The Teaching and Learning. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1978

Lindemann E: Symptomatology and management of acute grief. Am J Psychiatry 101:141-148, 1944

Luborsky L: Principles of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Manual for Supportive-Expressive Treatment. New York, Basic Books, 1984

Mahler MS, Pine F, Bergman A: The Psychological Birth of the Human Infant. New York, Basic Books, 1975

Markowitz JC, Klerman GL, Clougherty KE, et al: Individual psychotherapies for depressed HIV-positive patients. Am J Psychiatry 152:1504-1509, 1995

Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, Guilford, 1985

Massie MJ, Holland JC: Depression and the cancer patient. J Clin Psychiatry 51 (suppl): 12-19, 1990

Mezirow J: On critical reflection. Adult Education Quarterly 48:185-198, 1998

Misch DA: Basic strategies of dynamic supportive therapy. J Psychother Pract Res 9:173-189, 2000

Mitchell S: Relational Concepts in Psychoanalysis: An Integration. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1988

O'Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, et al: Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:881-887, 1992

Othmer E, Othmer S: The Clinical Interview Using DSM-IV, Vol 1. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994

Parad HJ, Parad LG: Crisis Intervention, Book 2: The Practitioner's Sourcebook for Brief Therapy. Milwaukee, WI, Family Service America, 1990

Parloff MB: Goals in psychotherapy: mediating and ultimate, in Goals of Psychotherapy. Edited by Mahrer AR. New York, Apple-ton-Century-Crofts, 1967, pp 5-19

Pinsker H: A Primer of Supportive Psychotherapy. Hillsdale, NJ, Analytic Press, 1997

Piper WE, Joyce AS, McCallum M, et al: Interpretive and supportive forms of psychotherapy and patient personality variables. J Consult Clin Psychol 66:558-567, 1998

Quality Assurance Project: Treatment outlines for the management of the somatoform disorders. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 19:397-407, 1985

Richland LE, Bjork RA, Finley JR, et al: Linking cognitive science to education: generation and interleaving effects, in Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 2005, pp 1850-1855

Rollnick S, Miller WR: What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother 23:325-334, 1995

Safran JD, Muran JC, Samstag LW: Resolving therapeutic alliance ruptures: a task analytic investigation, in The Working Alliance: Theory, Research and Practice. Edited by Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. New York, Wiley, 1994, pp 225-255

Sifneos PE: The prevalence of "alexithymic" characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom 22:255-262, 1973

Simon JC: Criteria for therapist self-disclosure. Am J Psychother 42:404-415, 1988

Stewart RL: Psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 4th Edition. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, MD, Williams & Wilkins, 1985, pp 1331-1365

Sullivan PR: Learning theories and supportive psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 128:119-122, 1971

Thomas EM, Weiss SM: Nonpharmacological interventions with chronic cancer pain in adults. Cancer Control 7:157-164, 2000

Tomkins MA: Cognitive-behavioral case formulation: the case of Jim. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration 6:97-105, 1996

Wallerstein RS: The psychotherapy research project of the Menninger Foundation: an overview. J Consult Clin Psychol 57:195-205, 1989

Walsh BJ, Wilson GT, Terence G, et al: Medication and psychotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 154:523-531, 1997

Werman DS: The Practice of Supportive Psychotherapy. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1984

Winnicott DW: The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development. London, Hogarth, 1965