CHAPTER 32

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) is a system of psychotherapy based on theories of pathological information processing in mental disorders. Treatment is directed primarily at modifying distorted or maladaptive cognitions and related behavioral dysfunction. Therapeutic interventions are usually focused and problem oriented. Although the use of specific techniques is a major feature of this approach, there can be considerable flexibility and creativity in the clinical application of CBT.

In this chapter we trace the historical origins of CBT, explain basic theories, and detail commonly used CBT techniques. The main focus is on the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders in adults; CBT procedures for eating disorders, personality disorders, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and other psychiatric conditions are briefly described. The extensive research on the effectiveness of CBT is summarized. Methods have been developed for using CBT with children and adolescents, but these applications are not discussed in this chapter. Readers who wish to learn about CBT for younger persons are referred to the excellent books on this topic, including those by Albano and Kearney (2000), March and Mulle (1998), and Reinecke et al. (2003).

The CBT approach to depression was first proposed by Beck in the early 1960s (Beck 1963, 1964). He had begun to study depression from a psychoanalytical perspective several years earlier but had been struck by incongruities between the "retroflexed hostility" concept of psychoanalysis and his observations that depressed individuals usually hold negatively biased constructions of themselves and their environment (Beck 1963, 1964). Subsequently, a comprehensive CBT method for depression was articulated, and the treatment model was extended to a variety of other conditions, including anxiety disorders (Beck 1967, 1976). CBT was described in a fully developed form in Cognitive Therapy of Depression (Beck et al. 1979).

CBT is linked philosophically to the concepts of the Greek Stoic philosophers and Eastern schools of thought such as Taoism and Buddhism (Beck et al. 1979). The writing of Epictetus in the Enchiridion ("Men are disturbed not by things which happen, but by the opinions about the things") captures the essence of the perspective that our ideas or thoughts are a controlling factor in our emotional lives. The existential phenomenological approach to philosophy, as exemplified in the writings of Kant, Jaspers, Frankl, and others, has also been linked to the basic concepts of CBT (Clark et al. 1999). A number of developments in the field of psychotherapy during the twentieth century contributed to the formulation of the CBT approach. The neo-Freudians, such as Adler, Horney, Alexander, and Sullivan, focused on the importance of perceptions of the self and on the salience of conscious experience. Other contributions came from the field of developmental psychology and from Kelly's theory of personal constructs (Clark et al. 1999). These writers stressed the significance of schemas (cognitive templates) in perceiving, assimilating, and acting on information from the environment. CBT also incorporates theories and treatment methods of behavior therapy (Meichenbaum 1977). Procedures such as activity scheduling, graded task assignment, exposure, and social skills training play a fundamental role in CBT (Beck et al. 1979; Wright et al. 2006).

In the half century since Beck introduced CBT concepts and methods, a very large research effort has documented the efficacy of this approach (for comprehensive reviews of the early research literature, see Dobson 1989; Gaffan et al. 1995; Robinson et al. 1990), and CBT methods have been studied for a broad range of problems, including depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse, and personality disorders. Some newer developments are CBT for psychosis (Kingdon and Turkington 2005), mindfulness-based CBT (Teasdale et al. 2000), and computer-assisted CBT (Andrews et al. 2010; Wright et al. 2005).

The cognitive model for psychotherapy is grounded on the theory that there are characteristic errors in information processing in psychiatric disorders, and that these alterations in thought processes are closely linked to emotional reactions and dysfunctional behavior patterns (Alford and Beck 1997; Beck 1976; Clark et al. 1999). For example, Beck and coworkers (Beck 1976) have proposed that people with depression are prone to cognitive distortions in three major areas—self, world/environment, and future (i.e., the "negative cognitive triad")—and that people with anxiety disorders habitually overestimate the danger or risk in situations. Cognitive distortions such as misperceptions, errors in logic, and misattributions are thought to lead to dysphoric moods and maladaptive behavior. Furthermore, a vicious cycle is perpetuated when the behavioral response confirms and amplifies negatively distorted cognitions.

Mr. S is a 45-year-old recently divorced, depressed man. After being rebuffed on his first attempt to ask a woman for a date, Mr. S had a series of dysfunctional cognitions such as, "You should have known better ... You're a loser ... There's no use trying." His subsequent behavioral pattern was consistent with these cognitions—he made no further social contacts and became more lonely and isolated. The negative behavior led to additional maladaptive cognitions (e.g., "No one will want me ... I'll be alone the rest of my life ... What's the use of going on?").

The CBT perspective can be summarized in a working model (Figure 32-1) that expands on the well-known stimulus-response paradigm (Wright et al. 2006). Cognitive mediation is given a central role in this model. However, an interactive relationship between environmental influences, cognition, emotion, and behavior is also recognized. It should be emphasized that this working model does not presume that cognitive pathology is the cause of specific syndromes or that other factors such as genetic predisposition, biochemical alterations, or interpersonal conflicts are not involved in the etiology of psychiatric illnesses. Instead, the model is used simply as a guide for the actions of the cognitive therapist in clinical practice. It is assumed that most forms of psychopathology have complex etiologies involving cognitive, biological, social, and interpersonal influences, and that there are multiple potentially useful approaches to treatment. In addition, it is assumed that cognitive changes are accomplished through biological processes and that psycho-pharmacological treatments can alter cognitions. This position is consistent with outcome research on CBT and pharmacotherapy (Blackburn et al. 1986) and with other studies that have documented neurobiological changes associated with conditioning in animals (Kandel and Schwartz 1982) or psychotherapy in humans (Goldapple et al. 2004).

The model in Figure 32-1 posits a close relationship between cognition and emotion. The general thrust of CBT is that emotional responses are largely dependent on cognitive appraisals of the significance of environmental cues. For example, sadness is likely when a person perceives an event (or memory of an event) in a negative way (e.g., as a loss, a defeat, or a rejection), and anger is common when a person judges that there are threats to oneself or one's loved ones. The cognitive model also incorporates the effects of emotion on cognitive processing. Heightened emotion can stimulate and intensify cognitive distortions. Therapeutic procedures in CBT involve interventions at all points in the model diagrammed in Figure 32-1. However, most of the effort is directed at stimulating either cognitive or behavioral change.

Beck and colleagues (Beck 1976; Beck et al. 1979; Dobson and Shaw 1986) have suggested that there are two major levels of dysfunctional information processing: 1) automatic thoughts and 2) basic beliefs incorporated in schemas. Automatic thoughts are the cognitions that occur rapidly while a person is in a situation (or recalling an event). These automatic thoughts usually are not subjected to rational analysis and often are based on erroneous logic. Although the individual may be only subliminally aware of these cognitions, automatic thoughts are accessible through questioning techniques used in CBT (Beck et al. 1979; Wright et al. 2006). The different types of faulty logic in automatic thinking have been termed cognitive errors (Beck et al. 1979). Descriptions of typical cognitive errors are provided in Table 32-1.

Figure 32-1. Basic cognitive-behavioral model.

Source. Reprinted from Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase ME: Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy: An Illustrated Guide (Core Competencies in Psychotherapy Series, Glen O. Gabbard, series ed.). Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2006, p. 5. Copyright 2006, American Psychiatric Publishing. Used with permission.

Schemas are deeper cognitive structures that contain the basic rules for screening, filtering, and coding information from the environment (Beck et al, 1979; Clark et al. 1999). These organizing constructs are developed through early childhood experiences and subsequent formative influences. Schemas can play a highly adaptive role in allowing rapid assimilation of data and appropriate decision making. However, in psychiatric disorders there are clusters of maladaptive schemas that perpetuate dysphoric mood and ineffective or self-defeating behavior (Beck 1976; Beck and Freeman 1990). Examples of adaptive and maladaptive schemas are presented in Table 32-2.

One of the basic tenets of CBT is that maladaptive schemas often lie dormant until they are triggered by stressful life events (Beck et al. 1979; Clark et al. 1999). The newly emerged schema then influences the more superficial level of cognitive processing so that automatic thoughts are consistent with the rules of the schema. This theory applies primarily to episodic disorders such as depression. In chronic conditions (e.g., personality disturbances and eating disorders), schemas that pertain to the self may be present consistently and may be more resistant to change than in depression or anxiety disorders (Beck and Freeman 1990).

Mrs. C, a 39-year-old schoolteacher who was married for the second time, was functioning well until her husband made an unwise financial investment. When the family's economic situation changed, Mrs. C became depressed and started to have crying spells in her classroom. During the course of CBT, several important schemas were uncovered. One of these was the maladaptive belief, "You'll fail, no matter how hard you try." This schema was associated with a host of negative automatic thoughts (e.g., "I messed up again ... We'll lose everything ... It's not worth the effort."). Although there had been a significant financial loss, and the marriage was stressed because of the situation, the emergence of Mrs. C's underlying schema led to an overgeneralization of the significance of the problem and a perpetuation of dysfunctional automatic thoughts.

|

Table 32-1. Cognitive errors |

|

|

Selective abstraction (sometimes termed "mental filter") |

Drawing a conclusion based on only a small portion of the available data |

|

Arbitrary inference |

Coming to a conclusion without adequate supporting evidence or despite contradictory evidence |

|

Absolutistic thinking ("all or none" thinking) |

Categorizing oneself or one's personal experiences into rigid dichotomies (e.g., all good or all bad, perfect or completely flawed, success or total failure) |

|

Magnification or minimization |

Over- or undervaluing the significance of a personal attribute, a life event, or a future possibility |

|

Personalization |

Linking external occurrences to oneself (e.g., taking blame, assuming responsibility, criticizing oneself) when there is little or no basis for making these associations |

|

Catastrophic thinking |

Predicting the worst possible outcome while ignoring more likely eventualities |

Source. Adapted from Wright et al. 2006.

|

Table 32-2. Adaptive and maladaptive schemas |

|

| Adaptive | Maladaptive |

|

No matter what happens, I can manage somehow. If I work at something, I can master it. I'm a survivor. Others can trust me. I'm lovable. People respect me. I can figure things out. If I prepare in advance, I usually do better. I like to be challenged. There's not much that can scare me. |

I must be perfect to be accepted. If I choose to do something, I must succeed. I'm a fake. Without a woman [man], I'm nothing. I'm stupid. No matter what I do, I won't succeed. Others can't be trusted. I can never be comfortable around others. If I make one mistake, I'll lose everything. The world is too frightening for me. |

The role of cognitive functioning in depression and anxiety disorders has been studied extensively. Information processing also has been examined in eating disorders, characterological problems, and other psychiatric conditions. In general, the results of this investigative effort have confirmed Beck's hypotheses (Beck 1963, 1964, 1976; Beck et al. 1979; Clark et al. 1999). A full review of this research is not attempted here. However, a synthesis of results of significant studies on depression and anxiety is provided. These findings have played an important role in both confirming and shaping the treatment procedures used in CBT. Cognitive pathology in eating disturbances, personality disorders, and psychoses is described in the section "Cognitive-Behavior Therapy Applications."

Reviews of the voluminous research on cognitive processes in depression have found strong evidence for a negative cognitive bias in this disorder (Clark et al. 1999). For example, distorted automatic thoughts and cognitive errors have been found to be much more frequent in depressed persons than in control subjects (Blackburn et al. 1986; Dobson and Shaw 1986).

Substantial evidence also has been collected to support the concept of the negative cognitive triad of self, world, and future (Clark et al. 1999), and a large group of investigations has established that one of the elements of this triad, a view of the future as hopeless, is highly associated with suicide risk. For example, Beck et al. (1985b) found that hopelessness was the strongest predictor of eventual suicide in a sample of depressed inpatients followed 10 years after discharge. CBT has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment approach for reducing hopelessness and suicide attempts (Brown et al. 2005).

Studies of information processing in anxiety disorders have provided additional confirmation for the cognitive model of psychopathology. Anxious patients have been found to have an attentional bias in responding to potentially threatening stimuli (Mathews and MacLeod 1987). Individuals with significant levels of anxiety are more likely than non-anxious persons to have a facilitated intake of information about potential threat; furthermore, those with anxiety disorders are prone to interpret environmental situations as being unrealistically dangerous or risky and to underestimate their ability to cope with these situations (Mathews and MacLeod 1987). Anxious patients also have been shown to have an enhanced recall for memories associated with threatening situations or past anxiety states (Cloitre and Liebowitz 1991) and misinterpretations of bodily stimuli (McNally and Foa 1987). Thus, dysfunctional thinking in anxiety disorders spans several phases of information processing, including attention, elaboration and inference, and retrieval from memory.

Comparisons of depressed and anxious patients have revealed differences between the two groups and common features of the disorders. Findings of studies on cognitive pathology in depression and anxiety disorders are summarized in Table 32-3.

|

Table 32-3. Pathological information processing in depression and anxiety disorders |

||

| Predominant in depression | Predominant in anxiety disorders | Common to both depression and anxiety disorders |

|

Hopelessness Low self-esteem Negative view of environment Automatic thoughts with negative themes Misattributions Overestimates of negative feedback Enhanced recall of negative memories Impaired performance on cognitive tasks requiring effort, abstract thinking |

Fears of harm or danger High sensitivity to information about potential threat Automatic thoughts associated with danger, risk, uncontrollability, incapacity Overestimates of risk in situations Enhanced recall of memories for threatening situations |

Demoralization Self-absorption Heightened automatic information processing Maladaptive schemas Reduced cognitive capacity for problem solving |

CBT is usually a short-term treatment, lasting from 5 to 20 sessions. In some instances, very brief treatment courses are used for patients with mild or circumscribed problems, or longer series of CBT sessions are used for those with chronic or especially severe conditions. However, the typical patient with major depression or an anxiety disorder can be treated successfully within the short-term format. Research studies on CBT for depression and anxiety disorders have typically used traditional "50-minute hours" to deliver treatment, and the book Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (Wright et al. 2006) focuses on the use of 50-minute sessions. However, psychiatrists have developed methods for combining CBT and medication in briefer sessions for some patients (Wright et al. 2010). In this chapter we describe traditional CBT delivered in 50-minute sessions. Readers interested in methods of adapting CBT for briefer sessions can find guidelines in High-Yield Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Brief Sessions: An Illustrated Guide (Wright et al. 2010).

After acute phase treatment with CBT is completed, booster sessions may be useful in some cases, particularly for individuals with a history of recurrent illness or incomplete remission. Booster sessions can help maintain gains, solidify what has been learned in CBT, and decrease the chances of relapse. Also, longer-term CBT can be woven into the ongoing psychiatric treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other conditions that are managed by psychiatrists over time periods of many years (Wright et al. 2010).

Although CBT is primarily directed at the here and now, knowledge of the patient's family background, developmental experiences, social network, and medical history helps guide the course of therapy. Collecting a thorough history is an essential component of the early phase of treatment. The therapist can augment the history taking in CBT by asking the patient to write a brief "autobiography" as one of the early homework assignments. This material is then reviewed during a subsequent therapy session.

The bulk of the therapeutic effort in CBT is devoted to working on specific problems or issues in the patient's present life. The problem-oriented approach is emphasized for several reasons. First, directing the patient's attention to current problems stimulates the development of action plans that can help reverse helplessness, hopelessness, avoidance, or other dysfunctional symptoms. Second, data on cognitive responses to recent life events are more readily accessible and verifiable than for events that happened years in the past. Third, practical work on present problems helps to prevent the development of excessive dependency or regression in the therapeutic relationship. Finally, current problems usually provide ample opportunity to understand and explore the impact of past experiences.

The therapeutic relationship in CBT is characterized by a high degree of collaboration between patient and therapist and an empirical tone to the work of therapy. The therapist and patient function much like an investigative team. They develop hypotheses about the validity of automatic thoughts and schemas or alternately about the effectiveness of patterns of behavior. A series of exercises or experiments is then designed to test the validity of the hypotheses and, subsequently, to modify cognitions or behavior. Beck et al. (1979) termed this form of therapeutic relationship collaborative empiricism. Methods of building a collaborative and empirical relationship are listed in Table 32-4.

The development of a collaborative working relationship is dependent on a number of therapist and patient characteristics. The "nonspecific" therapist variables that are important components of all effective psychotherapies (Wright et al. 2006) are equally significant in CBT (see Table 32-4). Professionals who are kind and understanding and can convey appropriate empathy make good cognitive-behavioral therapists. Other factors of significance are the ability of the therapist to generate trust, to demonstrate a high level of competence, and to exhibit equanimity under pressure.

The therapist usually is more active in CBT than in most other psychotherapies. The degree of therapist activity varies with the stage of treatment and the severity of the illness. Generally, a more directive and structured approach is emphasized early in treatment, when symptoms are severe. For example, a markedly depressed patient who is beginning treatment may benefit from considerable direction and structure because of symptoms such as helplessness, hopelessness, low energy, and impaired concentration. As the patient improves and understands more about the methods of CBT, the therapist can become somewhat less active. By the end of treatment, the patient should be able to use self-monitoring and self-help techniques with little reinforcement from the therapist.

Collaborative empiricism is fostered throughout the therapy, even when directive work is required. Although the therapist may suggest specific strategies or give homework assignments designed to combat severe depression or anxiety, the patient's input is always solicited and the self-help component of CBT is emphasized from the outset of treatment. Also, it is made clear that CBT is not an attempt to convert all negative thoughts to positive ones. Bad things do occur to people, and some individuals have behaviors that are ineffective or self-defeating. It is emphasized that in CBT one seeks to obtain an accurate assessment of 1) the validity of cognitions and 2) the adaptive versus maladaptive nature of behavior. If cognitive distortions have occurred, then the patient and therapist will work together to develop a more rational perspective. On the other hand, if actual negative experiences or characteristics are identified, they will attempt to find ways to cope or to change.

Additional procedures that cognitive therapists use to encourage collaborative empiricism are 1) providing feedback throughout sessions, 2) recognizing and managing transference, 3) customizing therapy interventions, and 4) using gentle humor. The therapist gives feedback to keep the therapeutic relationship anchored in the here and now, and to reinforce the working aspect of the therapy process. Comments are made frequently throughout the session to summarize major points, give direction, and keep the session on target. Also, the therapist asks questions at several intervals in each session to determine how well the patient has understood a concept or has grasped the essence of a therapeutic intervention. Because CBT is highly psychoeducational, the therapist functions to some degree as a teacher. Thus, discreet positive feedback is given to help stimulate and reward the patient's efforts to learn. On a cautionary note, however, the cognitive therapist needs to avoid overzealous coaching or providing inaccurate or overdone positive feedback. Such actions will usually undermine the development of a good collaborative relationship.

|

Table 32-4. Methods of enhancing collaborative empiricism |

|

|

Work together as an investigative team. Adjust therapist activity level to match the severity of illness and phase of treatment. Encourage self-monitoring and self-help. Obtain accurate assessment of validity of cognitions and efficacy of behavior. Develop coping strategies for real losses and actual deficits. Promote essential "nonspecific" therapist variables (e.g., kindness, empathy, equanimity, positive general attitude). Provide and request feedback on regular basis. Recognize and manage transference. Customize therapy interventions. Use gentle humor. |

|

Patients also are encouraged to give feedback throughout the sessions. In the beginning of treatment, patients are told that the therapist will want to hear from them regularly about how the sessions are going. What are the patient's reactions to the therapist? What things are going well? What would the patient like to change? What points are clear and make sense? What seems confusing?

A collaborative therapeutic relationship with frequent opportunities for two-way feedback generally discourages the formation of a transference neurosis. CBT methodology and the short-term nature of treatment promote pragmatic working relationships as opposed to recapitulations of dysfunctional early relationships. Nevertheless, significant transference reactions can occur. These are more likely with patients who have personality disorders or other chronic illnesses that require longer-term treatment. The formation of negative or problematic transference reactions is rare in conventional short-term CBT of persons with uncomplicated depression or anxiety disorders. When transference reactions occur, the cognitive therapist applies CBT procedures to understand the phenomenon and to intervene. Typically, automatic thoughts and schemas that pertain to the therapeutic relationship are identified, explored, and modified if possible.

Another feature of CBT that increases the collaborative nature of the therapeutic relationship is the customization of therapy interventions to meet the level of the patient's cognitive and social functioning. A profoundly depressed or anxious individual of low to average intelligence may require a primarily behavioral approach, with limited efforts at understanding concepts such as automatic thoughts and schemas, especially in the beginning of treatment. Conversely, a less symptomatic patient with higher intelligence and ability to grasp abstract concepts may be able to profit from schema assessment early in therapy. If treatment procedures are pitched at a proper level, the patient is more likely to understand the material of therapy and to form a collaborative relationship with the therapist who is directing the treatment.

The therapeutic relationship also can be enhanced by using gentle humor during CBT sessions. For example, the therapist may encourage the patient's sense of humor by providing opportunities to laugh together at some improbable situation or humorously distorted cognition. On occasion, the therapist may use hyperbole in a discreet manner to point out an inconsistency or an illogical conclusion. Humor needs to be injected carefully into the therapeutic relationship. Although some patients respond quite well to humor, others may be limited in their ability to use this feature of therapy. However, appropriate use of humor can strengthen the therapeutic relationship in CBT if patient and therapist are able to laugh with one another and to use humor to deflate exaggerated or distorted cognitions.

See Video 2 on the DVD accompanying the book High-Yield Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Brief Sessions: An Illustrated Guide (Wright et al. 2010) for an example showing that a cognitive-behavioral therapist can be quite active in a session, structuring therapy to focus on coping with specific problems while conveying considerable empathy and understanding.

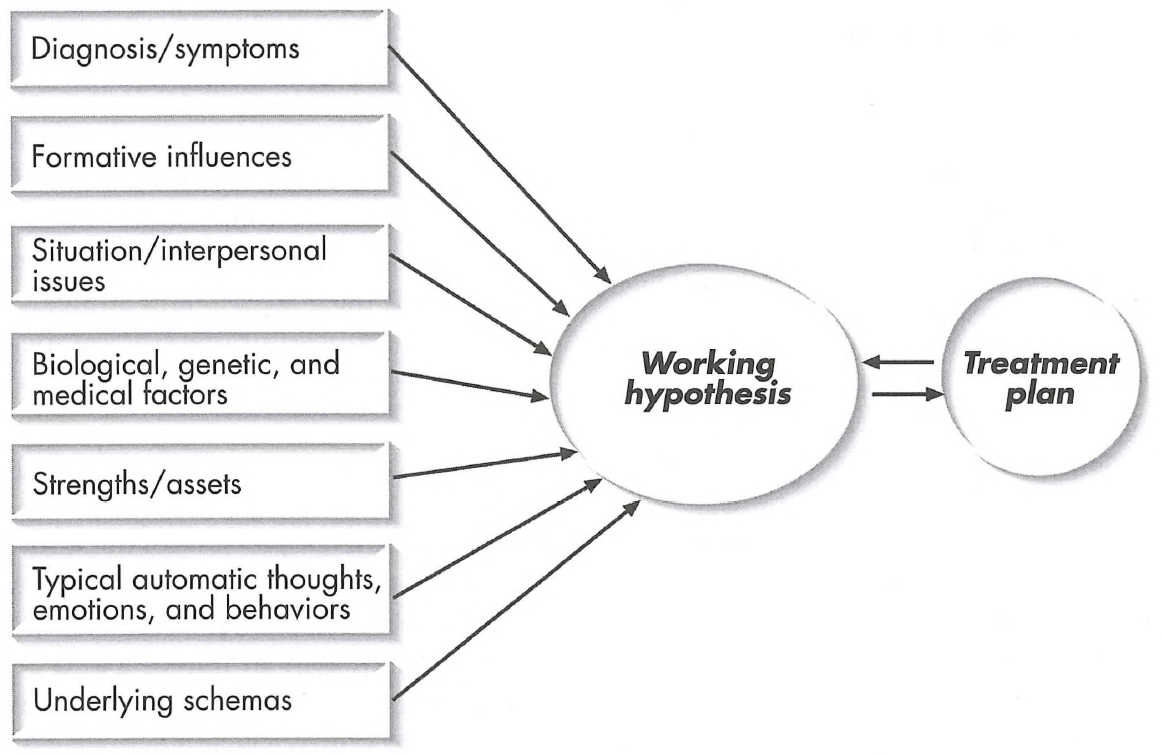

Assessment for CBT begins with completion of a standard history and mental status examination. Although special attention is paid to cognitive and behavioral elements, a full biopsychosocial evaluation is completed and used in formulating the treatment plan. The Academy of Cognitive Therapy, a certifying organization for cognitive therapists, has outlined a method for assessment and case conceptualization, which involves consideration of developmental influences, family history, social and interpersonal issues, genetic and biological contributions, and strengths and assets, in addition to key automatic thoughts, schemas, and behavioral patterns (see Figure 32-2). The book Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy: An Illustrated Guide (Wright et al. 2006) provides detailed methods, worksheets, and examples of use of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy formulation methods. Worksheets from this book can be downloaded from the American Psychiatric Publishing Web site (www.appi.org). Also, the Academy of Cognitive Therapy Web site (www.academyofct.org) supplies illustrations of how to complete case conceptualizations.

The key elements of the case conceptualization are 1) an outline of the most salient aspects of the history and mental status examination; 2) detailing of at least three examples from the patient's life of the relationship between events, automatic thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (specific illustrations of the cognitive model as it pertains to this patient); 3) identification of important schemas; 4) listing of strengths; 5) a working hypothesis that weaves together all of the information in numbers 1-4 with the cognitive and behavioral theories that most closely fit the patient's diagnosis and symptoms; and 6) a treatment plan (including choices for specific CBT methods) that is based on the working hypothesis. The conceptualization is continually developed throughout therapy and may be augmented or revised as new information is collected and treatment methods are tested.

One of the common myths about CBT is that it is a "manualized" therapy that follows a "cookbook" approach. Although it is true that CBT has been distinguished by clear descriptions of theory and methods, this treatment is guided by an individualized case conceptualization. Experienced therapists typically use considerable creativity in matching CBT interventions to the unique attributes, cultural background, life stresses, and strengths of each patient (Table 32-5).

Figure 32-2. Case conceptualization flow chart.

Source. Reprinted from Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase ME: Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy: An Illustrated Guide (Core Competencies in Psychotherapy Series, Glen O. Gabbard, series ed.). Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2006, p. 51. Copyright 2006, American Psychiatric Publishing. Used with permission.

Several of the structuring procedures commonly employed in CBT are listed in Table 32-6. One of the most important techniques for CBT is the use of a therapy agenda. At the beginning of each session, the therapist and patient work together to derive a short list of topics, usually consisting of two to four items. Generally, it is advisable to shape an agenda that 1) can be managed within the time frame of an individual session, 2) follows up on material from earlier sessions, 3) reviews any homework from the previous session and provides an opportunity for new homework assignments, and 4) contains specific items that are highly relevant to the patient but are not too global or abstract.

|

Table 32-5. Key elements of cognitive-behavior therapy case conceptualization |

|

|

History and mental status examination Examples of cognitive-behavioral model from patient's life Identification of major schemas List of strengths Working hypothesis Treatment plan |

|

Agenda setting helps to counteract hopelessness and helplessness by reducing seemingly overwhelming problems into workable segments. The agenda-setting process also encourages patients to take a problem-oriented approach to their difficulties. Simply articulating a problem in a specific manner often can initiate the process of change. In addition, the agenda keeps the patient focused on salient issues and encourages efficient use of the therapy time.

|

Table 32-6. Structuring procedures for cognitive-behavior therapy |

|

|

Set agenda for therapy sessions. Give constructive feedback to direct the course of therapy. Employ common cognitive-behavior therapy techniques on a regular basis. Assign homework to link sessions together. |

|

The agenda is set in a collaborative manner, and decisions to depart from the agenda are made jointly between therapist and patient. When work on an agenda item generates important information on a topic that was not foreseen at the beginning of the session, the therapist and patient discuss the merits of diverting or modifying the agenda. An excessively rigid approach to using a therapy agenda is not advocated. There must be sufficient flexibility to investigate promising new leads or to allow the patient to express significant thoughts or feelings that were unexpected at the beginning of the session. However, an overall commitment to setting and following the therapy agenda gives needed structure to patients who are unable to define problems clearly or think of ways to cope with them.

Feedback procedures described earlier are also used in structuring CBT sessions. For example, the therapist may observe that the patient is drifting from the established agenda or is spending time discussing a topic of questionable relevance. In situations such as these, constructive feedback is given to direct the patient back to a more profitable area of inquiry. Commonly used CBT techniques add an additional structural element to the therapy. Examples include activity scheduling, thought recording, and graded task assignment. These interventions, and others of similar nature, provide a clear and understandable method for reducing symptoms. Repeated use of procedures such as recording, labeling, and modifying automatic thoughts help to link sessions together, especially if the concepts and strategies that are introduced in therapy are then assigned as homework.

Psychoeducational procedures are a routine component of CBT. One of the major goals of the treatment approach is to teach patients a new way of thinking and behaving that can be applied in resolving their current symptoms and in managing problems that will be encountered in the future. The psychoeducational effort usually begins with the process of socializing the patient to therapy. In the opening phase of treatment, the therapist explains the basic concepts of CBT and introduces the patient to the format of CBT sessions. The therapist also devotes time early in treatment to discussing the therapeutic relationship in CBT and the expectations for both patient and therapist. Psychoeducational work during a course of CBT often involves brief explanations or illustrations coupled with homework assignments. These activities are woven into treatment sessions in a manner that emphasizes a collaborative, active learning approach. Some cognitive therapists have described the use of "mini-lectures," but a heavily didactic approach is generally avoided.

Psychoeducation can be facilitated with reading assignments and computer programs that reinforce learning, deepen the patient's understanding of CBT principles, and promote the use of self-help methods. Table 32-7 contains a list of useful psychoeducational tools, including a pamphlet, books, and a computer program, that teach the CBT model and encourage self-help. Most cognitive therapists liberally use psychoeducational tools as a basic part of the therapy process.

Much of the work of CBT is devoted to recognizing and then modifying negatively distorted or illogical automatic thoughts (Table 32-8). The most powerful way of introducing the patient to the effects of automatic thoughts is to find an in vivo example of how automatic thoughts can influence emotional responses. Mood shifts during the therapy session are almost always good places to pause to identify automatic thoughts. The therapist observes that a strong emotion such as sadness, anxiety, or anger has appeared and then asks the patient to describe the thoughts that "went through your head" just prior to the mood shift. This technique is illustrated in the example of Mr. B, a 50-year-old depressed man who had suffered several recent losses and had developed extremely low self-esteem.

Therapist: How did you react to your wife's criticism? Mr. B: (Suddenly appears much more sad and anxious) It was just too much to take. Therapist: I can see this really upsets you. Can you think back to what went through your mind right after I asked you the last question? Just try to tell me all the thoughts that popped into your head. Mr. B: (Pause, then recounts) I'm always making mistakes. I can't do anything right. There's no way to please her. I might as well give up. Therapist: I can see why you felt so sad. When these kinds of thoughts just automatically pop into your mind, you don't stop to think if they are accurate or not. That's why we call them automatic thoughts. Mr. B: I guess you're right. I hardly realized I was having those thoughts until you asked me to say them out loud. Therapist: Recognizing that you're having automatic thoughts is one of the first steps in therapy. Now let's see what we can do to help you with your thinking and with the situation with your wife.

Beck has described emotion as the "royal road to cognition" (Beck 1989). The patient usually is most accessible during periods of affective arousal, and cognitions such as automatic thoughts and schemas generally are more potent when they are associated with strong emotional responses. Hence, the cognitive therapist capitalizes on spontaneously occurring affective states during the interview and also pursues lines of questioning that are likely to produce an intense affect. One of the misconceptions about CBT is that it is an overly intellectualized form of therapy. In fact, CBT, as formulated by Beck et al. (1979), involves efforts to increase affect and to use emotional responses as a core ingredient of therapy.

One of the most frequently used procedures in CBT is Socratic questioning. There is no set format or protocol for this technique. Instead, the therapist must rely on his or her experience and ingenuity to formulate questions that will help patients move from having a "closed mind" to a state of inquisitiveness and curiosity. Socratic questioning stimulates recognition of dysfunctional cognitions and development of a sense of dissonance about the validity of strongly held assumptions.

|

Table 32-7. Psychoeducational materials and programs for cognitive-behavior therapy |

||

| Authors | Title | Description |

|

Barlow and Craske 2007 |

Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic |

Self-help for anxiety |

|

Basco 1999 |

Never Good Enough |

Book on perfectionism |

|

A.T. Beck et al. 1985a |

"Coping With Anxiety" |

Appendix to book |

|

A.T. Beck et al. 1995 |

"Coping With Depression" |

Brief pamphlet |

|

Burns 1980, 1999 |

Feeling Good |

Book with self-help program |

|

Foa and Wilson 2001 |

Stop Obsessing! How to Overcome Your Obsessions and Compulsions |

Self-help for obsessive-compulsive disorder |

|

Greenberger and Padesky 1995 |

Mind Over Mood |

Self-help workbook |

|

Wright and McCray 2012 |

Breaking Free From Depression: Pathways to Wellness |

Book with self-help program; integrates cognitive-behavioral therapy and biological approaches |

|

Wright et al. 2004 |

Good Days Ahead: The Multimedia Program for Cognitive Therapy |

Computer-assisted therapy and self-help program |

|

Table 32-8. Methods for identifying and modifying automatic thoughts |

|

|

Socratic questioning (guided discovery) Use of mood shifts to demonstrate automatic thoughts in vivo Imagery exercises Role-play Thought recording Generating alternatives Examining the evidence Decatastrophizing Reattribution Cognitive rehearsal |

|

Socratic questioning usually involves a series of inductive questions that are likely to reveal dysfunctional thought patterns. The use of this technique to identify automatic thoughts is illustrated in the case of Ms. W, a 42-year-old woman with an anxiety disorder.

Therapist: What things seem to trigger your anxiety? Ms. W: Everything. It seems like no matter what I do, I'm nervous all the time. Therapist: I suppose that "everything" could trigger your anxiety and that you have no control over it. But let's stop for a moment and see if there are any other possibilities. Is that okay? Ms. W: Sure. Therapist: Then try to think of a situation where your anxiety is very high and one where it's much lower. Ms. W: Well, a high-anxiety time would be whenever I try to go out in public, like to go shopping or to a party. And a low-anxiety time would be sitting at home watching TV. Therapist: So there's some variation depending on what you are doing at the time. Ms. W: I guess that's right. Therapist: Would you like to find out what's behind the variation? Ms. W: I guess. But I suppose it's just because being out with people makes me nervous and being at home feels safe. Therapist: That's one explanation. I wonder if there might be any others—ones that would give you some clues on how to get over the problem. Ms. W: I'm willing to look. Therapist: Well then, let's try to find out something about the different thoughts that you have about these two situations. When you think of going out to a party, what comes to mind? Ms. W: I'll be embarrassed. I won't have any idea what to say or do. I'll probably panic and run out the door.

This example depicts the typical use of Socratic questions early in the therapy process. Further questioning would be required to help the patient fully understand how dysfunctional cognitions are involved in her anxiety responses and how changing these cognitions could dampen her anxiety and promote a higher level of functioning.

Imagery and role-play are used as alternate methods of uncovering cognitions when direct questions are unsuccessful in generating suspected automatic thinking. These techniques also are selected when only a limited number of automatic thoughts can be brought out through Socratic questioning, and the therapist expects that more important automatic thoughts are present. Some patients may be able to use imagery procedures with few prompts or directions. In this case, the clinician may only need to ask the patient to imagine himself or herself back in a particularly troubling or emotion-provoking situation and then to describe the thoughts that occurred. However, most patients, particularly in the early phases of therapy, can benefit from "setting the scene" for the use of imagery. The patient is asked to describe the details of the setting. When and where did it take place? What happened immediately before the incident? How did the characters in the scene appear? What were the main physical features of the setting? Questions such as these help bring the scene alive in the patient's mind and facilitate recall of cognitive responses to the situation.

Role-play is a related technique for evoking automatic thoughts. When this procedure is used, the therapist first asks a series of questions to try to understand a vignette involving an interpersonal relationship or other social interchange that is likely to stimulate dysfunctional automatic thinking. Then, with the permission of the patient, the therapist briefly steps into the role of the individual in the scene and facilitates the playing out of a typical response set. Role-play is used less frequently than Socratic questioning or imagery and is best suited to therapeutic situations in which there is an excellent collaborative relationship and the patient is unlikely to respond to the role-play exercise with a negative or distorted transference reaction.

Thought recording is one of the most frequently used CBT procedures for identifying automatic thoughts (Wright et al. 2006). Patients can be asked to log their thoughts in a number of different ways. The simplest method is the two-column technique—a procedure that often is used when the patient is just beginning to learn how to recognize automatic thoughts. The two-column technique is illustrated in Table 32-9. In this case, the patient was asked to write down automatic thoughts that occurred in stressful or upsetting situations. Alternately, the patient could try to identify emotional reactions in one column and automatic thoughts in the other.

A three-column exercise could include a description of the situation, a list of automatic thoughts, and a notation of the emotional response. Thought recording helps the patient to recognize the effects of underlying automatic thoughts and to understand how the basic cognitive model (i.e., relationship between situations, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors) applies to his or her own experiences. This procedure also initiates the process of modifying dysfunctional cognitions.

There usually is no sharp division in CBT between the phases of eliciting and modifying automatic thoughts. In fact, the processes involved in identifying automatic thoughts often are enough to initiate substantive change. As the patient begins to recognize the nature of his or her dysfunctional thinking, there typically is an increased degree of skepticism regarding the validity of automatic thoughts. Although patients can start to revise their cognitive distortions without specific additional therapeutic interventions, modification of automatic thoughts can be accelerated if the therapist applies So-cratic questioning and other basic CBT procedures to the change process (see Table 32-8).

Techniques used for revising automatic thoughts include 1) generating alternatives, 2) examining the evidence, 3) thought recording, 4) reattribution, and 5) cognitive rehearsal. Socratic questioning is used in all of these procedures. Generating alternatives is illustrated in the case of Ms. D, a 32-year-old woman with major depression. The therapist's questions were pointed toward helping Ms. D to see a broader range of possibilities than she had originally considered.

Ms. D: Every time I think of going back to school, I panic. Therapist: And when you start to think of going to school, what thoughts come to mind? Ms. D: I'll botch it up. I won't be able to make it. I'll feel so ashamed when I have to drop out. Therapist: What else could happen? Anything even worse, or are there any better possibilities? Ms. D: Well, it couldn't get much worse unless I never even tried at all. Therapist: How would that be so bad? Ms. D: Then I'd just be the same—stuck in a rut, not going anywhere. Therapist: We can take a look at that conclusion later—that not going to school would mean that you would stay in a rut. But for now let's look at the other possibilities if you do try to go to school again. Ms. D: Okay. I guess there's some chance that it would go pretty well, but it'll be hard for me to manage school, the house, and all my family responsibilities. Therapist: When you try to step back from the situation and not listen to your automatic thoughts, what's the most likely outcome of your going back to school? Ms. D: It will be a difficult adjustment, but it's something I want to do. I have the intelligence to do it if I apply myself.

Examining the evidence is a major component of the collaborative empirical experience in CBT. Specific automatic thoughts or clusters of related automatic thoughts are set forth as hypotheses, and the patient and therapist then search for evidence both for and against each hypothesis. In the case of Ms. D, the thought "If I don't go to school, I'd just be the same—stuck in a rut, not going anywhere" was selected for an exercise in examining the evidence. The therapist believed that returning to school was probably an adaptive action for the patient to take. However, the therapist also thought that seeing further education as the only route to change would excessively load this activity with a "make or break" mentality and would promote a disregard for other modifications that might increase self-esteem and self-efficacy.

|

Table 31-9. Two-column thought recording |

|

| Event | Automatic thoughts |

|

Call from boss to submit a report |

I can't do this. I don't know what to do. It won't be acceptable. |

|

My wife asks me to help more around the house |

Nothing I do is ever enough. She thinks I don't try. |

|

Car won't start |

I was stupid to buy this car. Nothing works right anymore. This is the last straw. |

Five-column thought change records (TCRs; Beck et al. 1979; Table 32-10) or other similar devices for thought recording are standard tools used in modification of automatic thoughts. The five-column TCR is used to encourage both identification and change of dysfunctional cognitions. Two additional columns (rational thoughts and outcome) are added to the three-column thought record (events, automatic thoughts, and emotions) typically used to identify automatic thoughts. The patient is instructed to use this form to capture and change automatic thoughts. Either a stressful event or a memory of an event or situation is noted in the first column. Automatic thoughts are recorded in the second column and are rated for degree of belief (how much the patient believes them to be true at the moment they occur) on a 0-100 scale. The third column is used to observe the emotional response to the automatic thoughts. The intensity of emotion is rated on a 1-100 scale. The fourth column, rational thoughts, is the most critical part of the TCR. The patient is asked to stand back from the automatic thoughts, assess their validity, and then write out a more rational or realistic set of cognitions. There are a wide variety of procedures that can be used to facilitate the development of rational thoughts for the TCR.

Most patients can learn about cognitive errors and can start to label specific instances of erroneous logic in their automatic thoughts. This is often the first step in generating a more rational pattern of cognitive responses to life events. Previously described techniques such as generating alternatives and examining the evidence also are used by the patient in a self-help format when the TCR is assigned for homework. In addition, the therapist often is able to help the patient refine or add to the list of rational thoughts when the TCR is reviewed at a subsequent therapy session. Repeated attention to generating rational thoughts on the TCR is usually quite helpful in breaking maladaptive patterns of automatic and negatively distorted thinking.

The fifth column of the TCR, outcome, is used to record any changes that have occurred as a result of revising and modifying automatic thoughts. Although the use of the TCR will usually lead to the development of a more adaptive set of cognitions and a reduction in painful affect, on some occasions the initial automatic thoughts will prove to be accurate. In such situations, the therapist helps the patient take a problem-solving approach, including the development of an action plan, to manage the stressful or upsetting event.

|

Table 32-10. Thought Change Record—an example |

||||

| Event | Automatic thought(s) | Emotion(s) | Rational response | Outcome |

|

Describe:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Date: 3/15/13 |

||||

|

I wake up and I'm immediately troubled. I start to worry about work |

|

Sad: 90% Anxious: 80% |

|

Sad: 30% Anxious: 40% |

The use of reattribution techniques is based on findings of studies on the attributional process in depression. Depressed individuals have been found to have negatively biased attributions in three dimensions: global versus specific, internal versus external, and fixed versus variable (Abramson et al. 1978). Several different types of reattribution procedures are employed, including psychoeducation about the attributional process, Socratic questioning to stimulate reattribution, written exercises to recognize and reinforce alternate attributions, and homework assignments to test the accuracy of attributions.

Cognitive rehearsal is used to help uncover potential negative automatic thoughts in advance and to coach the patient in ways of developing more adaptive cognitions. First, the patient is asked to use imagery or role-play to identify possible distorted cognitions that could occur in a stressful situation. Second, the patient and therapist work together to modify the dysfunctional cognitions. Third, imagery or role-play is used again, this time to practice the more adaptive pattern of thinking. Finally, for a homework assignment, the patient is asked to try out the newly acquired cognitive patterns in vivo.

See Video 6 on the DVD accompanying the book High-Yield Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Brief Sessions: An Illustrated Guide (Wright et al. 2010) for an example of CBT methods for helping a patient revise negative automatic thoughts that are interfering with her ability to cope with the significant stresses in her life.

The process of identifying and modifying schemas is somewhat more difficult than changing negative automatic thoughts because these core beliefs are more deeply embedded and usually have been reinforced through years of life experience. However, many of the same techniques described for automatic thoughts are employed successfully in therapeutic work at the schema level. Procedures such as Socratic questioning, imagery, role-play, and thought recording are used to uncover maladaptive schemas (Table 32-11).

As the patient gains experience in recognizing automatic thoughts, repetitive patterns begin to emerge that may suggest the presence of underlying schemas. Therapists have several options at this point. A psychoeducational approach can be used to explain the concept of schemas (which may be alternately termed core beliefs or basic assumptions) and their linkage to more superficial automatic thoughts. Patients may then start to recognize schemas on their own. However, when the patient first starts to learn about basic assumptions, the therapist may need to suggest that certain schemas might be operative and then engage the patient in collaborative exercises that test these hypotheses.

Modification of schemas may require repeated attention, both in and out of therapy sessions. One commonly used procedure is to ask the patient to list in a therapy notebook all the schemas that have been identified to date. The schema list can be reviewed before each session. This technique promotes a high level of awareness of schemas and usually encourages the patient to place issues pertaining to schemas on the agenda for therapy.

CBT interventions that are particularly helpful in modifying schemas include examining the evidence, listing advantages and disadvantages, generating alternatives, and using cognitive rehearsal. After a schema has been identified, the therapist may ask the patient to do a pro/con analysis (examining the evidence) using a double-column procedure. This technique usually induces the patient to doubt the validity of the schema and to start to think of alternate explanations.

|

Table 32-11. Methods for identifying and modifying schemas |

|

|

Socratic questioning Imagery and role-play Thought recording Identifying repetitive patterns of automatic thoughts Psychoeducation Listing schemas in therapy notebook Examining the evidence Listing advantages and disadvantages Generating alternatives Cognitive rehearsal |

|

Ms. R is a 24-year-old woman with depression and bulimia. During the course of her CBT, Ms. R identified an important schema that was affecting both the depression and the eating disorder ("I must be perfect to be accepted."). By examining the evidence, she was able to see that her schema was based at least in part on faulty logic (Table 32-12).

Ms. R also used the technique of listing advantages and disadvantages as part of the strategy to modify this maladaptive schema (Table 32-13). Some schemas appear to have few, if any, advantages (e.g., "I'm stupid"; "111 always lose in the end"), but many schemas have both positive and negative features (e.g., "If I decide to do something, I must succeed"; "I always have to work harder than others or I'll fail"). The latter group of schemas may be maintained even in the face of their dysfunctional aspects because they encourage hard work, perseverance, or other behaviors that are adaptive. Yet the absolute and demanding nature of the schemas ultimately leads to excessive stress, failed expectations, low self-esteem, or other deleterious results. Listing advantages and disadvantages helps the patient to examine the full range of effects of the schema and often encourages modifications that can make the schema both more adaptive and less damaging. In Ms. R's case, this exercise set the stage for another step of schema modification, generating alternatives (Table 32-14).

The list of alternative schemas will usually include several different options, ranging from rather minor adjustments to extensive revisions in the schema. The therapist uses Socratic questioning and other CBT techniques such as imagery and role-play to help the patient recognize potential alternative schemas. A "brainstorming" attitude is encouraged. Instead of trying to be sure that a revised schema is entirely accurate at first glance, the therapist usually suggests trying to generate a variety of modified schemas without initially considering their validity or practicality. This stimulates creativity and gives the patient further encouragement to step aside from long-standing rigid schemas.

After alternatives are generated and discussed, the therapy turns toward examining the potential consequences of changing basic attitudes. Cognitive rehearsal can be used in the therapy session to test a schema modification. This may be followed by a homework assignment to try out the revised schema in vivo. Therapist and patient work together to choose the most reasonable modifications for underlying schemas and to reinforce learning these new constructs through multiple practice sessions in therapy sessions and in real-life experiences.

|

Table 32-12. Schema modification through examining the evidence |

|

|

Schema: "I must be perfect to be accepted." |

|

|

Evidence for |

Evidence against |

|

The better I do, the more people seem to like me. Women who have a perfect figure are most attractive to men. My parents have the highest standards; they are always pushing me to do better. |

Others who aren't "perfect" seem to be loved and accepted. Why should I be different? You don't have to have a perfect figure. Hardly anybody has one—just the models on television. My parents want me to do well. But they'll probably accept me as long as I try to do my best, even if I don't meet all of their expectations. This statement is absolute and sets me up for failure, because no one can be perfect all the time. |

|

Table 32-13. Schema modification through listing advantages and disadvantages |

|

|

Schema: "I must be perfect to be accepted." |

|

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

I've tried very hard to be the best. I've received top marks in school. I'm in lots of activities, and I've won dancing competitions. |

I never really feel accepted because I've never reached perfection. I'm always down on myself. I've developed bulimia. I'm obsessed with my body size. I have trouble accepting my successes. I drive myself too hard and can't enjoy ordinary things. |

|

Table 32-14. Schema modification through listing advantages and disadvantages |

|

Schema: "I must be perfect to be accepted." |

|

Possible alternatives |

|

People who are successful are more likely to be accepted. If I try to do my best (even if it's not perfect), others are likely to accept me. I would like to be perfect, but that's an impossible goal. I'll choose certain areas to try to excel (school, work, and career) and not demand perfection everywhere. You don't need to be perfect to be accepted^ I'm worthy of love and acceptance without trying to be perfect. |

Behavioral interventions are used in CBT to 1) change dysfunctional patterns of behavior (e.g., helplessness, isolation, phobic avoidance, inertia, bingeing and purging); 2) reduce troubling symptoms (e.g., tension, somatic and psychic anxiety, intrusive thoughts); and 3) assist in identifying and modifying maladaptive cognitions. Table 32-15 presents a list of behavioral techniques. As discussed earlier in this chapter, the basic cognitive-behavioral model (see Figure 32-1) suggests that there is an interactive relationship between cognition and behavior. Thus, behavioral initiatives should influence cognition, and cognitive interventions should have an impact on behavior.

The Socratic questions used in cognitively oriented procedures have a direct parallel when the emphasis is on behavioral change. The therapist asks a series of questions that help differentiate actual behavioral deficits from negatively distorted accounts of behavior. Depressed and anxious patients usually over-report their symptomatic distress or the difficulties they have in managing situations. Often, well-framed questions can reveal cognitive distortions and also stimulate change as the patient considers the negative impact of dysfunctional behavior. Four specific behavioral techniques—activity scheduling, graded task assignment, exposure, and coping cards—are explained below. A more detailed description of behavioral methods is available in Wright et al. (2006) or Meichenbaum (1977).

Activity scheduling is a structured method of learning about the patient's behavioral patterns, encouraging self-monitoring, increasing positive mood, and designing strategies for change. A daily or weekly activity log is employed in which the patient is asked to record what he or she does during each hour of the day and then to rate each activity for mastery and pleasure on a 0-10 scale. When the activity record is first introduced, the patient usually is asked to make a record of baseline activities without attempting to make any changes. The data are then reviewed in the next therapy session. Almost invariably, the patient rates some activities higher than others on mastery and/or pleasure.

Mr. G, a 48-year-old depressed man who had told his therapist that "I don't enjoy anything anymore," described several activities on his daily activity log that contradicted this statement. Reading while sitting alone was rated as a 6 on mastery and 8 on pleasure, and attending his son's choir concert was rated as 7 on mastery and 10 on pleasure. Conversely, attempting to work in his home office was rated as a 1 on mastery and a 0 on pleasure. Discussion of the activity scheduling assignment with Mr. G helped him to see that he was still capable of performing reasonably well in certain activities and also that he was able to derive considerable enjoyment from some of his actions. In addition, the schedule was used to target problem areas (e.g., working in his home office) that would require further work in therapy. Finally, the activity schedule provided data that could be used in adjusting Mr. G's daily routine to promote a heightened sense of mastery and greater enjoyment.

|

Table 32-15. A Behavioral procedures used in cognitive therapy |

|

|

Questioning to identify behavioral patterns Activity scheduling with mastery and pleasure recording Self-monitoring Graded task assignment Behavioral rehearsal Exposure and response prevention Coping cards Distraction Relaxation exercises Respiratory control Assertiveness training Modeling Social skills training |

|

Another behavioral procedure, the graded task assignment, can be used when the patient is facing a situation that seems excessively difficult or overwhelming. A challenging behavioral goal is broken down into small steps that can be taken one at a time. The graded task assignment is somewhat similar to the systematic desensitization protocols that are used in traditional behavior therapy; however, a cognitive component is added to the methodology. An added emphasis is placed on improving self-esteem and self-efficacy, countering hopelessness and helplessness, and using the graded task assignment to disprove maladaptive thoughts and schemas. With depressed individuals, the graded task assignment typically is used as a problem-solving technique. This stepwise approach, coupled with cognitive techniques such as Socratic questioning and thought recording, can reactivate the patient and help him or her to focus in a productive manner. For example, a graded task assignment was used in the case of Mr. G, the 48-year-old man introduced in the previous case study.

One of the particularly troublesome items uncovered with activity scheduling was Mr. G's difficulty in getting to work at his home office. Socratic questioning revealed that Mr. G had been unable to work in his home office for over 6 weeks. Mail, bills, and correspondence with friends were piled up to the point that he saw the situation as impossible. Cognitions related to this problem included automatic thoughts such as "It's too much ... I've procrastinated too long this time ... I'm totally swamped ... I can't handle it."

The therapist and patient constructed a series of steps that encouraged Mr. G to approach the task and eventually master the problem. The graded task assignment included the following steps: 1) walk into the office and sit down at the desk for at least 15 minutes; 2) spend at least 20 minutes sorting letter mail into categories; 3) open and discard any junk mail; 4) open and stack all bills; 5) clean office; 6) open e-mail, delete all messages that don't require a response, and answer messages that do; 7) balance checkbook; and 8) pay all current or overdue bills. Reasonable goals for specific time intervals were discussed, and the therapist used coaching, Socratic questioning, and other cognitive techniques to help Mr. G accomplish the task.

Video 5 on the DVD accompanying the book High-Yield Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Brief Sessions: An Illustrated Guide (Wright et al. 2010) shows an example of behavioral methods for helping a depressed patient reactivate and restore a sense of enjoyment in daily activities.

Exposure techniques are a central part of cognitive-behavioral approaches to anxiety disorders. For example, a phobia can be conceptualized as an unrealistic fear of an object or a situation coupled with a conditioned pattern of avoidance. Treatment can proceed along two complementary lines: 1) cognitive restructuring to modify the dysfunctional thoughts and 2) exposure therapy to break the pattern of avoidance. Typically, a hierarchy of feared stimuli is developed with the patient. The hierarchy should contain a number of different stimuli that cause varying degrees of distress. Usually the items are ranked by degree of distress. One commonly used system involves rating each item on a scale from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the maximum distress possible. After the hierarchy is established, the therapist and patient work collaboratively to set goals for gradual exposure, starting with the items that are ranked lower on the distress scale. Breathing training, relaxation exercises, and other behavioral methods (see Table 32-15) may be used to enhance the patient's ability to carry out the exposure protocol. Exposure can be done with imagery in treatment sessions or in vivo. Also, innovative virtual-reality methods have been developed for exposure therapy (Rothbaum et al. 1995). Clinician-administered exposure therapy is frequently used as part of the cognitive-behavioral approach to simple phobias, panic disorder with agoraphobia, and social phobia.

Coping cards are another commonly used method to achieve behavioral change. The therapist helps the patient to identify specific actions that are likely to help him or her cope with an anticipated problem or put CBT skills into action. These ideas are then written down on a small card, which the patient carries as a reminder and as a tool to help in solving problems. Coping cards often contain both cognitive and behavioral interventions, as illustrated in Figure 32-3.

Other behavioral techniques used in CBT include behavior rehearsal (a procedure that is usually combined with cognitive rehearsal, described earlier in "Modifying Automatic Thoughts"), response prevention (a collaborative exercise in which the patient agrees to stop a dysfunctional behavior, such as prolonged crying spells, and to monitor cognitive responses), relaxation exercises, respiratory control, assertiveness training, modeling, and social skills training (Meichenbaum 1977; Wright et al. 2006).

Computer-assisted CBT offers significant potential for increasing the efficiency of cognitive-behavioral interventions and improving patient access to treatment (Andrews et al. 2010; Spurgeon and Wright 2010). For example, Wright et al. (2002, 2005) have developed a multimedia form of computer-assisted CBT that is designed to be user friendly and to be suitable for a wide range of patients, including those with no previous computer or keyboard experience. This online program, "Good Days Ahead," features large amounts of video, along with interactive self-help exercises such as thought change records, activity schedules, and coping cards. A randomized controlled trial of computer-assisted CBT for depression conducted with a prototype of the Wright et al. program found that computer-assisted CBT was equivalent to standard CBT, even though the total therapist time in computer-assisted CBT was reduced to about 4 hours (Wright et al. 2005). Subjects in this study were taking no medications. Computer-assisted CBT and standard CBT were both highly effective in relieving symptoms of depression, and both were superior to a delayed-treatment control condition. Another multimedia CBT program, "Beating the Blues," was found to be effective in a controlled trial with primary care patients (Proudfoot et al. 2004). Persons with depression and anxiety who received treatment with this computer program had significantly greater improvement in depression than those who received treatment as usual. Both of these multimedia programs ("Good Days Ahead" and "Beating the Blues") have been well accepted by patients (Proudfoot et al. 2004; Wright et al. 2002). Meta-analyses of computer-assisted CBT have found that this form of treatment has been efficacious in a variety of studies for both depression and anxiety disorders (Andrews et al. 2010).

Virtual reality methods for computer-assisted therapy have been directed primarily at phobias and other anxiety disorders. The virtual environment is used to simulate feared situations and to promote exposure therapy. Controlled research has supported the efficacy of virtual reality as part of a CBT treatment package for fear of flying, height phobia, and other phobias (Krijn et al. 2004; Pull 2005; Rothbaum et al. 2000). This method is also showing promise in the treatment of social anxiety disorder and panic disorder with agoraphobia (Pull 2005) as well as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For these conditions, the virtual environment may include simulations of other people or places, such as crowded public spaces, public speaking experiences, and scenes from war zones.

Situation:

My girlfriend comes in late or does something else that makes me think she doesn't care.

Coping strategies:

Spot my extreme thinking, especially when I use absolute words like never or always.

Stand back from the situation and check my thinking before I start yelling or screaming.

Think of the positive parts of our relationship—I tkink she does love me.

We've been together for 4 years, and I want to make it work.

Take a "time-out" if I start getting into a rage, Tell her that I need to take a break to calm down. Take a brief walk or go to another room.

Figure 32-3. Mr. W's coping card.

This example shows how Mr. W, a middle-aged man with bipolar disorder, developed an effective coping strategy for managing anger in situations with his girlfriend.

Source. Reprinted from Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase ME: Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy: An Illustrated Guide (Core Competencies in Psychotherapy Series, Glen O. Gabbard, series ed.). Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2006, p. 120. Copyright 2006, American Psychiatric Publishing. Used with permission.

Although not developed or studied as full treatment programs, a number of CBT-based "apps" for smartphones have also been introduced. These apps have been used for self-monitoring, psychoeducation, and specific problems such as insomnia (Aguileria and Muench 2012). Surveys of potential users have found a significant demand for mobile apps in behavioral health, but the potential impact and extent of use of CBT apps is not yet known (Aguileria and Muench 2012).

Possible contributions of fully developed forms of computer-assisted CBT may include decreased cost of treatment, increased access to therapy, more rapid socialization to treatment procedures and techniques, and lowered burden on therapists to teach basic CBT concepts. Opportunities for improved efficiency of treatment, advances in the design of computer programs, and the proliferation of computers in society may promote greater use of computer tools for CBT.

CBT procedures have been described for a large number of diagnostic categories (Beck 1993). Although there are no contraindications to using this treatment approach, CBT is usually not attempted with patients who have marked brain disease. CBT can be considered a primary treatment for 1) disorders in which it has been proven to be effective in controlled research (e.g., unipolar depression [nonpsychotic], anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and psychophysiological disorders) and 2) other conditions for which a clearly detailed treatment method has been developed (e.g., personality disorders, substance abuse) and there is some evidence for CBT's effectiveness. CBT should be considered an adjunctive therapy for disorders such as major depression with psychotic features, bipolar illness, and schizophrenia, in which there is clear evidence for the effectiveness of biological treatments but in which the effects of CBT alone compared with pharmacotherapy have not been studied.

Several studies have examined possible predictors for outcomes in CBT. Simons et al. (1985) observed that high scores on a test of self-control predicted an enhanced response to CBT compared with a tricyclic antidepressant. Although several later studies (Jarrett et al. 1991; Wetzel et al. 1992) failed to replicate this finding, one other study (Burns et al. 1994) partially replicated it. Miller et al. (1989) found that high levels of cognitive dysfunction in depressed inpatients were associated with a superior response to combined treatment with CBT and pharmacotherapy as compared with pharmacotherapy alone. Chronicity and symptom severity have been associated with poorer response to CBT (e.g., Thase et al. 1993, 1994), although these findings may reflect the more negative prognostic impact of these variables. When CBT has been compared directly with pharmacotherapy, most studies have found little relationship between severity or endogenous subtype and differential treatment outcome (e.g., DeRubeis et al. 1999; Thase 2001).

Investigations of biological predictors have yielded suggestive results. Dexamethasone nonsuppression was associated with a poorer response to both CBT and pharmacotherapy in one study (McKnight et al. 1992). Thase et al. (1996a) found that poorer response to an intensive inpatient CBT program was associated with high levels of urinary free cortisol levels. In a large (N=90) outpatient study, an abnormal sleep profile (defined by multiple disturbances of electroencephalographic sleep recordings) was associated with a lower recovery rate and higher risk for relapse (Thase et al. 1996b). More recently, a specific alteration in cortical activation (as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning) was strongly associated with short-term CBT response (Siegle et al. 2006, 2012). Although these studies suggest that various biological markers of depression may be associated with response or nonresponse to CBT, research to date does not justify the use of laboratory tests to select patients for CBT.

Clinical experience has suggested that those patients who do not have severe character pathology (especially borderline or antisocial features), who have previously formed trusting relationships with significant others, who have a belief in the importance of self-reliance, and who have a curious or inquisitive nature, are especially suitable for CBT (Wright et al. 2006). Above-average intelligence is not associated with better outcome, and CBT procedures can be simplified for those with subnormal intellectual skills or impaired learning and memory functioning. Of course, most patients do not have a full combination of these ideal features. A flexible approach can be employed in which CBT procedures are customized to match the special characteristics of each patient's social background, intellectual level, personality structure, and clinical disorder (Wright et al. 2006).

The basic procedures described in this chapter are used in all CBT applications. However, the targets for change, selection of techniques, and timing of interventions may vary depending on the condition being treated and the format for therapy. A full discussion of the multiple applications and formats for CBT is beyond the scope of this chapter. The reader is referred to comprehensive books on CBT for a more detailed accounting of the modifications of this treatment approach for different clinical disorders (see "Suggested Readings" at end of chapter). In this portion of the chapter, we briefly examine the distinctive features of CBT for six common psychiatric illnesses: depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, personality disorders, psychosis, and bipolar disorder. Data on CBT effectiveness are presented in the later section "Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy."