CHAPTER 29

Brief Psychotherapies

Brief psychotherapy refers to a class of treatments that seek to accelerate change through the active, focused interventions of therapists and enhanced patient involvement. Treatment is designed to be brief and is limited, somewhat arbitrarily, from the start to less than 6 months or less than 24 sessions. In the past several decades, various brief approaches to therapy have evolved, ranging from single-session treatments and several sessions of strategic interventions to short-term psychodynamic modalities that frequently exceed 20 sessions. At the same time, rigorously performed outcome studies of brief therapy have matched patients and presenting concerns likely to benefit from specific approaches. This has also led to the application of brief therapies to a wider range of patients, including targeted interventions for severe conditions. The overarching message from this research is that the value of short-term work is significant but also highly dependent on the characteristics of patients and their therapists.

Surprisingly, Freud's own cases showed that psychoanalytic therapy was frequently of brief duration. For example, in Studies on Hysteria (Breuer and Freud 1893-1895/1955), Freud described three of his patients as having treatments that lasted for 9 weeks (Lucie R.), 7 weeks (Emmy Von N.), and one session (Katharina)! However, this brevity was not by design, and he tended not to focus on treatment outcome in his writing. Instead, he emphasized that having a neutral therapist who was not overly involved in how treatment would turn out could lead to important discoveries about the development of psychopathology (Fisher and Greenberg 1985).

Although Freud saw patients with short-term cases, brief therapy arguably dates back to the publication of Alexander and French's (1946) classic work Psychoanalytic Therapy: Principles and Applications. They were the first to formally place the therapist in the active role of promoting patient health. Change, they argued, was not primarily a function of insight but of experience. Therefore, the therapist's role was to foster "corrective emotional experiences." These are replays of previous conflicted situations that end more positively within the helping relationship. This reformulation took therapists out of their historic role as "blank screens" and cast them as active treatment agents who could use their relationships with patients to catalyze needed developmental experiences. Research has gone on to support the usefulness of this more active approach. Lengthy treatments, which associated therapeutic gains primarily with the attainment of patient insights, have not turned out to be as central to change as many psychoanalysts assumed (Fisher and Greenberg 1996). With the writings of Peter Sifneos (1972), James Mann (1973), David Malan (1976), and Habib Davanloo (1980), brevity has become an accepted part of the psychoanalytic lexicon.

The rise of behavior therapies contributed significantly to the prominence of brief work. Behavioral treatments cast the therapist in the role of teacher. No longer was therapy about self-exploration. Rather, it was intended to teach coping skills and alter learned action patterns. This permitted therapy to be highly circumscribed, emphasizing directive teaching and structured homework assignments between sessions. Behavior therapy found its first formal exposition in the writings of B.F. Skinner in the 1950s, along with the influential Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition (Wolpe 1958). By the 1970s, behavior therapy had become part of the therapeutic mainstream (Skinner 1974).

Albert Ellis (1962) applied the learning paradigm to cognition with rational-emotive therapy in the 1950s. This blended the psychodynamic interest in the patient's inner life with hands-on behavioral methods. The cognitive method of teaching patients to unlearn dysfunctional thought patterns and acquire new, constructive ones continued with Aaron Beck's writings in the 1960s and the influential Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders (A.T. Beck 1976). The combination of a tight treatment focus and structured patient involvement between sessions ensured that cognitive therapy, like its behavioral sibling, possessed core ingredients of brevity.

Yet a third type of brief therapy emerged with the writings of Jay Haley (1963, 1976), whose Strategies of Psychotherapy and Problem-Solving Therapy drew heavily on the clinical practices of Milton Erickson (Erickson and Haley 1967). Erickson viewed the presenting concerns of patients as failed efforts to solve normal life problems. These lead to cycles in which attempted solutions reinforce initial problems, much as an insomniac patient's active efforts to sleep sustain wakefulness. The role of the therapist, Erickson held, is neither as significant other (as in brief psychodynamic work) nor as cognitive-behavioral teacher. Rather, the therapist is a problem solver who interrupts and redirects these self-reinforcing cycles. This frequently could be accomplished in a matter of several sessions through the prescription of directed tasks. With the publication of Watzlawick et al.'s (1974) classic work on change processes, the strategic approach became a therapeutic staple, notably in the family therapy literature.

In the 1980s, rising health care costs led to managed care, and brief therapy found an economic and a practice rationale. Budman and Gurman (1988) found that therapy could be conducted in a time-effective manner. Research suggesting that brief modalities were effective for a variety of patients and problems (Steenbarger 1992) supported the adoption of short-term work among clinicians and managed health care organizations. The movement toward evidence-based medicine spurred the development of manualized psychotherapeutic treatments, which, by their very nature, are highly structured and limited in duration (Huppert et al. 2006). With such popularity, however, also emerged concerns about the limitations of such treatments, especially for severe and persistent emotional disorders and conditions with high relapse rates (Reed and Eis-man 2006); these concerns are being systematically addressed and brief therapies devised for personality disorders and psychotic disorders (A.T. Beck et al. 2004; Wright et al. 2010). It is fair to say that by the twenty-first century, brief therapies had become the practice rule rather than the exception among psychotherapists.

Although "common factors" are essential and form the base of all successful therapies (Greenberg 2012), the various brief therapies make different assumptions about the causes of presenting problems and the specific procedures necessary to alter them. These approaches cluster within three broad models: relational, learning, and contextual (Steenbarger 2002). Because of their distinctive assumptions and practice patterns, each of these models defines brevity differently. We describe the key elements of each model and suggest that the reader enrich the text by referring to detailed illustrative cases and video clips provided in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition (Dewan et al. (2012).

Relational modalities include short-term psychodynamic treatments and interpersonal therapy (IPT). The key assumption of these approaches is that the presenting problems of patients reflect difficulties in significant relationships. Several important differences are evident between short-term dynamic therapies and IPT, chief among them being the focus on the therapeutic relationship as a vehicle for change.

Psychodynamic brief therapies share the premise of all psychodynamic therapies that the presenting problems of patients result from an internalization of conflicts from earlier significant relationships. The anxiety from these conflicts is controlled through defenses that aid short-term coping but forestall the conscious assimilation and working through of core relational issues. As a result, these issues resurface in future relationships whenever similar anxiety and conflict are experienced, triggering old patterns of defense. These coping efforts are no longer appropriate to present-day relationship contexts, yielding secondary conflict and the consequences that typically bring people to therapy. Thus, the psychodynamic therapist views presenting problems as more than symptoms of an underlying disorder. They are the result of outmoded, currently maladaptive (defensive) efforts in the face of repeated interpersonal conflict.

Traditional psychodynamic therapy works backward from presenting complaints to underlying core conflicts. The chief therapeutic strategy in this process is interpretation, as therapists promote insight into outmoded defenses and repeated interpersonal struggles. The therapeutic relationship becomes the locus for such insight as those struggles are reenacted in the transference relationship. As patients replay their maladaptive defensive patterns and interpersonal struggles within sessions, the dynamically oriented therapist engages the real relationship—the mature alliance between the self-observing patient and the therapist—to help the patient become aware of what is happening and why. With this insight into repetitive patterns and their consequences, patients can then attempt to rework the ways in which they handle interpersonal threats within the safe confines of the helping relationship.

Because traditional long-term psychodynamic work requires an unfolding of historical patterns within the therapeutic relationship, it cannot be an abbreviated treatment. The focus on interpretation as a chief therapeutic tool and insight as a goal—with in-session work and an exhaustive exploration of the past as the primary context for change efforts—ensures that such therapy spans months, if not years, of analysis.

Several features of short-term psychodynamic therapy enable it to accelerate this change curve:

In short, brief dynamic therapists, unlike their traditional counterparts, take an active role in the helping process, fostering and sustaining a treatment focus and initiating interventions within this focus to challenge maladaptive defensive patterns and provide new, corrective relationship experiences (Table 29-1). Although such short-term work may not be brief by managed-care standards, often extending to 20 or more sessions, it significantly abbreviates the traditional treatment course of psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy. There is good evidence that brief dynamic therapy is effective for a wide range of patients (Ab-bass et al. 2006; Leichsenring 2009). Furthermore, studies have found that both in brief therapy and in traditional psychoanalysis, the strength of the relationship, persuasion, suggestion, catharsis, and the therapist as a model are much more pivotal to the change process than was previously recognized (Eisenstein et al. 1994; Fisher and Greenberg 1996; Wallerstein 1986, 1989).

Like dynamic therapy, IPT sustains a focus on relationship issues and also on interpersonal communication. Flowever, it is distinct from dynamic therapy in that the primary focus of IPT is on the patients' relationships and communication patterns with others who are currently important in their lives: the IPT therapist does not seek to understand how past events and relationships may have influenced current relationships and therefore does not work on transference relationships with patients nor reenactments of past interpersonal patterns. As a result, IPT tends to be more brief than most short-term psychodynamic therapies, often only 12 sessions (Stuart 2012). Indeed, unlike short-term psychodynamic therapy, IPT began in 1984 as a brief manualized treatment that has been successfully applied to a variety of presenting problems and interpersonal concerns (Stuart and Robertson 2012). In general, IPT has been found to be particularly efficacious for patients with mood and anxiety disorders (Cuipjers et al. 2008; Markowitz and Weissman 2009) and may not be appropriate for patients with personality disorders who have difficulty forming and sustaining therapeutic alliances (Stuart 2012).

IPT is based on the biopsychosocial diathesis-stress model. An acute interpersonal crisis (stress), particularly in the absence of sufficient social support, will cause distress and symptoms in the area in which the person is vulnerable (diathesis). The first one or two sessions are used for a comprehensive assessment. The patient's family history and health status are elicited. What is their attachment style: secure, anxious/preoccupied, dismissive, or fearful/avoidant? An interpersonal inventory consists of a succinct account of the important people in a patient's life. How effectively does the patient offer and ask for support? These threads are woven into an interpersonal formulation.

IPT targets three problem areas (Weissman et al. 2000, 2007):

|

Table 29-1. Differences between short-term psychodynamic and traditional therapies |

||

| Short-term dynamic therapies | Traditional dynamic therapies | |

|

Therapeutic focus |

Focal relationship patterns |

Personality change |

|

Therapist role |

Active significant other |

Blank screen |

|

Emphasized change mechanism |

Corrective relationship experiences |

Insight |

|

Mechanism for dealing with resistances |

Challenge and confrontation |

Interpretation |

In IPT, the therapist takes an active role in treatment, sustaining the focus on these issues. After assessment and establishment of a focus, the rationale and goals of treatment are made explicit and a therapeutic contract executed. Current interpersonal concerns are then explored, and patient and therapist brainstorm ways of handling them (Table 29-2). These potential solutions form the basis for between-session efforts (homework) by patients, securing their active involvement in treatment. Subsequent sessions review and refine these efforts, casting the therapist in the role of collaborative problem solver. Resistance to change is dealt with in a straightforward manner by the therapist, not as pattern reenactments to be interpreted and worked through. The goal of therapy is to promote independent functioning on the part of the patient, as well as symptom relief. As Stuart and Robertson (2012) emphasized, IPT, unlike other therapies, does not presume a complete termination of therapy at the end of treatment. Rather, therapists assume that future sessions may be necessary to maintain gains and prevent relapse. Also unlike other therapies, IPT is more welcoming of the concomitant use of medications, which is consistent with IPT's bio-psychosocial diathesis-stress model.

In summary, the relational model of therapy achieves brevity by creating a circumscribed focus on the patient's interpersonal patterns and by limiting treatment to patient groups able to sustain this focus. Whereas the role of the therapist is different in short-term dynamic therapy (a significant other) compared with IPT (a collaborative problem solver), the ultimate goal is similar: altering problem patterns by generating new, constructive relational experiences.

|

Table 29-2. Differences between interpersonal therapy and short-term psychodynamic therapy |

||

| Interpersonal therapy | Short-term psychodynamic therapy | |

|

Therapeutic focus |

Current patterns in interpersonal communications and attachments |

Patterns repeated in past, present, and therapeutic relationships |

|

Therapist role |

Problem solver |

Transference object |

|

Emphasized change mechanism |

Attempting new patterns of communication and altered expectations in extratherapeutic relationships |

Corrective relationship experiences within therapy |

|

Structure |

Brief; manualized |

Time-effective; open-ended |

The learning model of treatment, which includes a wide range of cognitive-behavioral therapies, starts from a different set of premises from those in the relational model. The presenting concerns of patients are viewed as learned maladaptive patterns that can be unlearned. Moreover, patients are seen as capable of acquiring new, adaptive patterns of thought and action through skill development. As a result, the learning therapies feature the therapist in an active, directive teaching mode and the patient as a student. This structuring of the helping relationship lends itself to active skill rehearsal within sessions and directed homework between meetings. The combination of a tight learning focus and active practice of techniques ensures that most learning therapies are short term by their very nature.

For purposes of exposition, it is helpful to distinguish between primarily behavioral treatments that emphasize exposure as a central therapeutic ingredient and cognitive approaches that more broadly target dysfunctional patterns of information processing for restructuring. Although these approaches have elements that overlap (e.g., patients exposed to traumatic cues may rehearse thoughts that emphasize self-control), the relative degree of emphasis is different, which affects the conduct and brevity of treatment.

Learning therapies that use exposure as a core therapeutic ingredient include the work of Edna Foa and colleagues (Gilli-han et al. 2012) in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder and David Barlow's (2002) work on panic disorder. Treatment typically begins with a period of assessment and psychosocial education. During this time, patients may keep detailed logs that track the appearance of symptoms and the circumstances surrounding them. Examination of these logs during the early sessions helps to generate a focus on the specific triggers for symptom appearance. Concurrently, therapists educate patients about the learning model, explaining how and why symptoms appear. This can be highly reassuring for patients with an illness such as panic disorder who may be bewildered by their symptoms.

Also early in treatment, exposure-based learning therapies introduce specific skills designed to help control symptoms. These can include efforts at relaxation, thought stopping, self-reassurance, and seeking social support. The skills are typically introduced one at a time, explained in detail as part of the aforementioned psychosocial education, modeled in session by the therapist, and rehearsed in session by patients. For instance, the slow breathing skill is taught in the first session (e.g., silently and slowly drawing out the word "calm" while exhaling very slowly—"caaaaaaaaaallllllllllmmmm"—modeled by the therapist and practiced by the patient. A recording of the therapist guiding the patient through 10-15 such breathing cycles is made for the patient's use at home. The patient practices this several times a day and is reminded that he can use this technique whenever he feels anxious (Gillihan et al. 2012). Only after patients understand and master skills in session do they rehearse the skills as part of their between-session homework.

An important component of the brevity of these therapies stems from the subsequent employment of these skills. Once triggers for presenting symptoms have been identified, they are deliberately introduced into therapy sessions via imagery and in vivo exercises. Patients are thus required to actively use their coping skills while they are exposed to the very stimuli that have provoked symptoms. For example, a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder secondary to rape is treated with prolonged imaginal exposure—that is, she is asked to reexperience the rape in as vivid detail as possible. This produces high anxiety, so support and relaxation techniques are used to help the patient habituate to these memories. This is repeated several times in each session, and the patient repeatedly listens to a tape of this retelling at home. Once this imagined rape loses its power to traumatize her, the patient is encouraged to gradually confront the rape in reality (in vivo), such as by a visit to the scene (presuming it is normally a safe place), first with a friend and then by herself. A patient with a hand-washing compulsion might be exposed to dirt and then prevented from washing his hands (i.e., exposure and response prevention). A patient experiencing panic might simulate panic experiences by spinning in a chair and then using cognitive and relaxation skills to maintain composure.

Such in-vivo exposure provides patients with firsthand emotional experiences of mastery that appear to accelerate the pace of symptom resolution. Once initial gains are achieved, efforts at generalization commence, and the skills are used across a variety of symptom-related cues (Table 29-3). Variations in technique—and the specific needs of patients—dictate whether the exposure is attempted in a gradual way or in a more rapid, intensive fashion. Interestingly, research suggests that a significant immersion into anxiety-arousing situations often may be therapeutic because patients benefit from extended sessions of exposure (Gillihan et al. 2012). As Shapiro's (2001) work suggested, exposure appears to be effective because of the opportunity it affords patients to reprocess cues associated with distress.

Whereas the exposure therapies have found their greatest application in the treatment of anxiety disorders, cognitive reprocessing therapies have been applied to depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and child and adolescent disorders (Hollon and Beck 2004), and more recently to personality disorders, eating disorders, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia (A.T. Beck et al. 2004; J.S. Beck et al. 2012; Wright et al. 2010). Symptoms, according to this approach, can be traced to automatic thought patterns that distort information processing and produce negative thoughts about self, others, and the future (cognitive triad). The goal of therapy is to identify these thought patterns, challenge them, and replace them with more constructive alternatives (J.S. Beck 1995). The combination of in-session rehearsal and out-of-session homework targeting core patterns of automatic thought ensures that the cognitive work is time efficient.

|

Table 29-3. Comparison of learning and relational models of brief therapy |

||

| Learning models | Relational models | |

|

View of presenting problems |

Learned maladaptive patterns of behavior and thought |

Internalized relationship conflicts and patterns |

|

Goal of therapy |

Unlearning old dysfunctional patterns; acquiring new constructive ones |

Novel interpersonal experiences that can be internalized |

|

Therapist role |

Directive teacher |

Facilitator of exploration |

|

Emphasized change mechanism |

Rehearsal of skills and experiences of mastery during problematic situations |

Changing interpersonal patterns in current relationships |

|

Structure |

Brief, often manualized or highly structured |

Sometimes brief and manualized (interpersonal therapy); sometimes not (short-term dynamic) |

Like the exposure-based learning therapies, cognitive restructuring treatments begin with a period of assessment and psychosocial education. The education in the cognitive model helps patients understand the relation between thoughts and feelings and the ways in which automatic thought patterns can sustain unwanted patterns of emotion and action. J.S. Beck et al. (2012) presented a common example: a patient returns from work and sees disarray in her apartment (situation) and thinks, Tm a total basket case. Til never get my act together" (automatic thoughts), which makes her feel sad (emotion) and heavy in her body (physiological reaction), leading to her lying down with her coat on (behavior). Throughout cognitive therapy, therapists engage patients in a highly collaborative manner, minimizing resistance and sustaining the helping alliance.

This collaboration continues with the maintenance of a dysfunctional thought record in which patients track events, reactions to those events, and mediating beliefs. Most of these core beliefs pertain to the sense of being helpless (e.g., "I am incompetent," "I am trapped," "I am inferior") or unlovable (e.g., "I am ugly," "I am worthless," "I will be rejected") (J.S. Beck et al. 2012); patients then form schemas around these core beliefs that filter and color future perception, which creates cognitive distortions. The dysfunctional thought record enables therapists to create cognitive conceptualizations of patients, linking core beliefs to automatic thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. The record also helps patients observe their distortions as they are occurring and realize their role in maintaining presenting symptoms. From the observations of patients and therapists, a focus for intervention emerges that targets specific cognitive distortions.

Central to the cognitive restructuring therapies is a Socratic process of guided discovery between therapist and patient that questions these distortions and encourages a consideration of alternative explanations. What is the evidence for and against this idea? Is there an alternate explanation? What is the worst or best that could happen? How would you cope with the worst? What is the most realistic outcome? What is the effect of believing the automatic thought? What could be the effect of changing it? (J.S. Beck et al. 2012). This process also occurs between sessions because therapists encourage patients to use thought records to evaluate their own degree of belief in the distortions. Each dysfunctional thought pattern is viewed by therapist and patient as a hypothesis to be questioned and tested. Behavioral experiments devised during sessions are carried out between meetings to provide direct experiential tests of patient assumptions. The goal of this "collaborative empiricism" (J.S. Beck 1995) is to create vivid experiences of disconfirmation for patients that aid the building of new, accurate schemas (Table 29-4).

Whereas the exposure therapies target specific conditioned responses for extinction, the cognitive restructuring therapies entail a comprehensive collaborative relationship between therapists and patients that evaluates and restructures a range of cognitive patterns. For this reason, as well as the differences between the therapies in the range of problems that they typically address, the exposure treatments tend to be more brief than the restructuring therapies, with the former frequently lasting fewer than 10 sessions and the latter typically ranging between 10 and 20 visits. Despite the differences in their specific methods, many similarities link these learning therapies. They are highly structured and focused, with active assignments during and between sessions. They seek to challenge directly and undercut the patterns that bring patients to therapy, achieving brevity by replacing verbal exploration with experiences of mastery.

The aforementioned relational and learning therapies begin with a common premise—that the presenting concerns of patients are acquired over the life span as the result of problematic experiences: faulty relationships or faulty learning. Both therapies, in that sense, place the locus of problems within the patient. Contextual brief therapies, on the other hand, do not view problems as intrinsic to patients. Rather, problems are seen as artifacts of person-situation interactions that, once identified, can be rapidly modified. Short-term couples therapies, for instance, view problem patterns as sustained by the reciprocal contributions of each partner (Baucom et al. 2012). Because difficulties are seen as situational, targeted problem-solving interventions to alter these situations make the contextual therapies among the briefest of therapies.

Strategic therapies, including single-session treatments (Hoyt et al. 1992), view presenting concerns as the result of attempts at solutions that unwittingly reinforce the very problems patients are attempting to address (Rosenbaum 1990). A person concerned about rejection in relationships, for instance, might interact in guarded ways, leading others to avoid future interaction. The problem, from the vantage point of the strategic therapist, is a function of the patient's construal of the situation and the ways in which that construal are reinforced through social interaction (Quick 2008). It can be resolved through skillful reframing that opens the door to new action alternatives (Fisch et al. 1982) and the creation of directed tasks (Levy and Shelton 1990) that disconfirm existing understandings. The goal of treatment is to catalyze initial change that patients can then sustain on their own, not to effect fundamental changes of personality. For this reason, strategic therapies are intentionally brief.

|

Table 29-4. Differences between exposure and cognitive restructuring brief therapies |

||

| Exposure therapies | Cognitive restructuring therapies | |

|

View of presenting problems |

Conditioned patterns of emotion and behavior triggered by internal and environmental cues |

The result of information processing distortions arising from dysfunctional schemas |

|

Goal of therapy |

Deconditioning of patterns through skill enactment during exposure to symptom triggers |

Challenging and replacing cognitive distortions with realistic, constructive alternatives |

|

Therapist role |

Directive teacher |

Collaborative empiricist |

|

Emphasized change mechanism |

Firsthand experiences of mastery |

Altered cognitive schemas |

|

Structure |

Brief, with circumscribed symptom focus; often manualized or highly structured |

More extended, with broader focus; often manualized or highly structured |

The initial interview of strategic therapy is designed to identify current complaints of patients and their attempts at resolution. The therapist's conceptualization is neither a diagnosis nor a formulation of personality but a description of the current situational factors that help to maintain the patient's presenting concerns. This description includes the people involved in the patient's concerns and the roles they take, the patient's view of the situation, the sequence of behaviors that result in the patient's complaints, and the specific contexts in which these complaints arise (Rosenbaum 1990). From this conceptualization, therapists gain an appreciation of the ways in which patients feel stuck in their attempts at resolution and can begin to generate ways of becoming unstuck.

As Rosenbaum (1990) emphasized, the goal of the therapy is not to find a solution for a patient's problem but to create a situation that lends itself to spontaneous goal attainment. Many times, fresh construals and solutions will result simply when old patterns are disrupted and patients behave in new and unpredictable ways (Quick 2008). The patient who is afraid of social interaction, for instance, will not interact with others if rejection is anticipated. That same patient, however, may view him- or herself to be a kind, sensitive person and will initiate interactions to help others. Such interactions offer the possibility of positive feedback and fresh incentives to seek out further social contact. By changing the patient's context—from being stuck in a pattern to enacting a strength—the therapist allows naturally occurring growth processes to take their own course. In that sense, strategic therapy is a process for removing barriers to change and not a self-contained change process in itself (Table 29-5).

An offshoot of strategic therapy, solution-focused brief therapy, provides a somewhat different contextual approach to short-term change. Solution-focused brief therapists start from the premise that people are changing all the time, enacting solution patterns as well as problem ones (Ratner et al. 2012). Indeed, there is an important sense in this therapy in which problems do not exist at all. When patients cannot reach their goals, they at some point identify that they have a problem. This reification becomes self-fulfilling: the more patients focus on their problems, the more troubled they feel and act. Equally important, such a problem focus blinds patients to the occasions in which they do, in fact, reach their goals.

The aim of solution-focused brief therapy is to break this self-fulfilling conceptualization. The therapist accomplishes this by focusing on solution patterns rather than on problems. Thus, in the initial assessment therapists ask patients to identify positive pre-session changes and occasions during which problems either do not occur or occur less often or less intensely (Walter and Peller 1992). Enacting these exceptions to problem patterns—doing more of what is already working (de Shazer 1988; O'Hanlon and Weiner-Davis 1989)—is the focus of therapy, not an analysis of core conflicts or a teaching of skills to remediate deficits. Because the therapy is not initiating new behavior and thought patterns but instead is building on existing ones, it tends to be highly targeted, lasting several sessions on average (Steenbarger 2012).

Several other factors contribute to the brevity of solution-focused therapy, including working within patient goals to minimize resistance, maintaining a tight solution focus, involving patients in between-session efforts to enact solution patterns, and having a high degree of therapist activity (Steenbarger 2012). The emphasis on patient strengths undercuts the cycle of problem-based thinking and stuck emotion and behavior. The focus on constructive change also paves the way for therapists and patients to frame goals in positive action terms that can be supported by directed homework tasks extending the solution patterns. Such goals can be formulated with minimal historical exploration, which further contributes to brevity.

Gingerich and Eisengart (2000) listed the specific techniques that facilitate solution-focused brief therapy:

|

Table 29-5. Contextual models of brief therapy |

|

Presenting complaints are the result of self-reinforcing problem-solution cycles. Problems are a function of patients and their context, not internal to patients. Goal of therapy is initiating change, not seeing it to completion. Role of therapist is to structure experiences that undermine the stuck behavior of patients. Therapy is highly abbreviated. |

Brief Vignette

Ms. I is a medical student who came to therapy with a complaint of "out-of-control eating." She was successful in both her academic and social lives but did not feel comfortable with her weight or looks. Since her early college years, she had experienced episodes of overeating and extended sessions in front of a mirror during which she would look for signs of weight gain or other physical imperfections. At such times, she would greatly restrict her eating, only to later overcompensate and turn to food for solace. Such binges left her feeling guilty and further exacerbated her self-criticism. Interestingly, however, she never purged the food. Ms. I was convinced that because of her appearance and problems, she would never be able to sustain a romantic relationship. It was recent disruption of her medical school studies, however, that brought her into therapy.

Information gathered during the initial interview suggested that Ms. I did not have any earlier history of emotional or behavioral problems and did not meet formal diagnostic criteria for either an eating disorder or a mood disorder. This raised the therapist's confidence that solution-focused brief therapy could be appropriate. Given that Ms. I described her problem as being "out of control," the therapist asked for examples of occasions, since making the appointment, when Ms. I had felt more in control. Ms. I responded by talking about her clinical work during her clerkship and her growing confidence in working with patients. She described her problem as an 8 out of 10 in severity, indicating that she only felt good after a great day on the floors.

Further inquiry revealed that Ms. I also felt good after good performances on her tests and did not overeat or criticize herself on those occasions. Instead, she simply went out with friends and enjoyed herself. Ms. I described pediatrics as her first love and said it was what she had always wanted to do. The therapist complimented Ms. I on her caring attitude toward children, pointing out that a good pediatrician knows how to be reassuring and nurturing.

At that point, the therapist asked Ms. I if she would be willing to close her eyes and try an experiment. The therapist asked her to imagine that she was taking care of a young girl named Marie. Marie was frightened and nervous and would not eat. But Marie needed to eat in order to stay healthy. The therapist asked Ms. I to visualize sitting with Marie, talking with her, and helping to feed her. The exercise was emotional for Ms. I, who clearly empathized with the little girl, imagining holding her and offering her food and love.

At the end of the exercise, the therapist suggested that Ms. I could be her own patient and that she could take care of herself the way she was caring for Marie. The therapist suggested that at the end of each day upon coming home, Ms. I keep her white coat on and maintain the role of Dr. I. She was to imagine that she had a patient to take care of at home, named Ms. I, who was having difficulty feeling good about herself and was expressing that difficulty through how she ate. Her role as Dr. I was to take care of her patient by reaching out to her and feeding her in a loving manner.

Ms. I found the assignment to be challenging but did not binge eat during the subsequent week. Interestingly, she recalled a lullaby her mother had sung to her when she was young. By playing the lullaby in her head while she ate, Ms. I found it easier to take care of "her patient." Once she thought of herself as a vulnerable child, she was able to recruit her caring self and the skills she was developing as a physician in training. A major step of progress occurred when Ms. I did poorly in a clinical rotation and started to criticize herself but was able to "keep her white coat on" and allow herself a small snack. Shortly thereafter, Ms. I began a dating relationship. The therapist explained to Ms. I that she had not learned anything new. She had always been a caring person and a capable young physician. Therapy simply helped her apply those strengths to herself.

(For a more detailed presentation of the case of Ms. I, as well as video segments of specific solution-focused brief therapy interventions, please see "Solution-Focused Brief Therapy: Doing What Works," by Brett Steenbarger, Ph.D., in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition [Dewan et al. 2012].)

One way solution-focused brief therapy differs from strategic brief therapies is that it lends itself to manualization. Such manuals (de Shazer 1988; Ratner et al. 2012; Walter and Peller 1992) view therapy as a series of steps involving the identification of pre-session change, the formulation of solution-based goals, the use of the miracle question and scaling questions to elicit exceptions to patient complaints, the provision of feedback to support change, and the assignment of tasks to extend solution patterns (Table 29-6). Like strategic therapies, solution-focused therapy relies less on verbal exploration and more on direct experience to break circular patterns that interfere with the achievement of patient goals. The goal of both therapies is not so much to resolve a problem as it is to help patients see that what they thought was a problem was in fact a function of their punctuation of experience—their ways of construing themselves and the world.

The foregoing discussion has focused on describing the major schools of brief therapy and highlighted the differences among these models. Therapists approaching patients from relational, learning, and contextual vantage points differ in their conceptualization of presenting problems and the procedures necessary to address these. These therapeutic modalities differ in other ways as well:

|

Table 29-6. Differences between strategic and solution-focused brief therapies |

||

| Strategic therapies | Solution-focused therapies | |

|

View of presenting problems |

Attempted solutions to problems further reinforce those problems |

Deemphasis of problems and emphasis on exceptions to problem patterns |

|

Goal of therapy |

Interruption of problem cycles and attempts to initiate new action patterns |

Creating solution patterns out of exceptions to problem patterns |

|

Therapist role |

Facilitator of change through structured tasks and experiences |

Facilitator of change through construction of solution patterns |

|

Emphasized change mechanism |

Reframing of problems and direct experiences of novel action patterns |

Undermining of problem focus through enactment of solutions |

|

Structure |

Highly abbreviated but not highly structured |

Highly abbreviated; often manualized or highly structured |

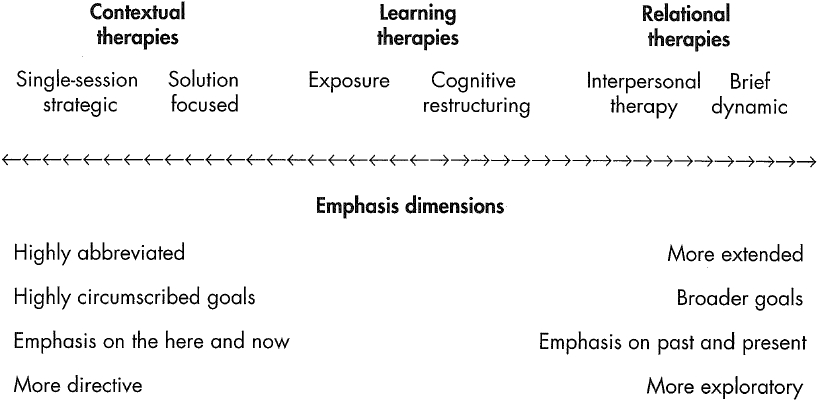

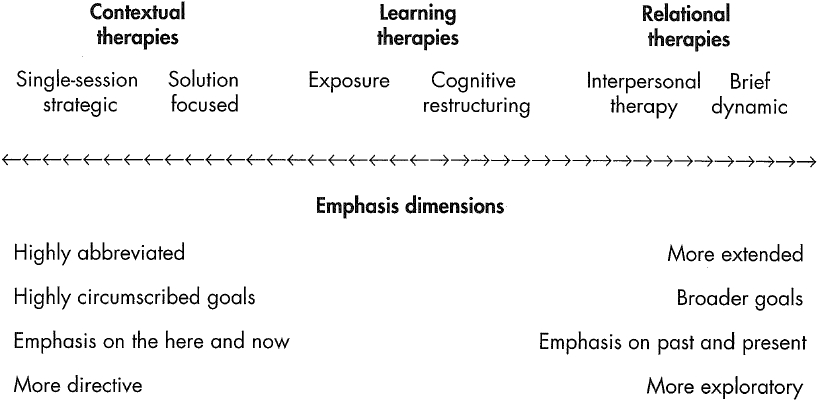

Because of the described differences, we can conceptualize the brief therapies along a continuum, ranging from highly abbreviated and highly structured contextual therapies to more exploratory relational treatments. The briefest treatments emphasize that the patient's presenting complaints are artifacts of self-construal and can be addressed in the here and now through experiences that undermine those construals. These highly abbreviated therapies view patients as capable of growth and change and seek only to catalyze these naturally occurring processes. The more extended short-term therapies place presenting problems into a historical context and stress insight and corrective emotional experiences in a developed relationship as essential to change. Patients are viewed as caught in maladaptive relational patterns that are replayed across a variety of situations and thus need more than a change catalyst. Between these extremes, the learning therapies emphasize here-and-now unlearning of overlearned dysfunctional patterns and the acquisition of constructive alternatives through structured learning experiences (Figure 29-1).

Despite these evident differences, many underlying similarities among the brief therapies help to account for their brevity. It is not surprising that the brief therapies embody common ingredients (Greenberg 2012); a wealth of research (Lambert and Ogles 2004; Wampold 2001) has found that factors shared by the various psychotherapies account for a significant proportion of the variance in patient change. A list of common factors across all psychotherapy models (both brief and longer term) typically would include the creation of a strong therapist-patient alliance, opportunities to confront and face problems, the development of patient mastery experiences, and the facilitation of patient hope and positive expectations about the future. Specific ingredients found across the short-term treatments include the following:

Figure 29-1. Differences among brief therapy models.

Steenbarger (2002) suggested that the brief therapies have structural similarities characterized by a series of change stages (Table 29-7). Treatment begins with a period of engagement in which patient and therapist forge a working alliance that engages the patient's desire for change and mutually creates targets for change efforts. Central to the formation of this alliance is a translation of patients' presenting complaints into the language of a particular therapeutic approach, enabling patients to perceive their problems in a new light and fashion fresh possibilities for change. Therapy then draws on the procedures of the particular approach to create discrepant experiences that challenge old patterns of thought and behavior, facilitating new understandings and action patterns. The final phase of therapy seeks to consolidate these new understandings and skills by generalizing them to a variety of situations, thus cementing an internalization of new patterns and helping to prevent relapse. The brief therapies, from this vantage point, may be viewed as devices for generating novel experiences in the context of enhanced experiencing (Steenbarger 2006), accelerating learning processes that occur in all psychotherapies.

An impressive body of research documents the effectiveness of psychotherapy across a variety of presenting problems (Lambert 2013; Roth and Fonagy 2006). This is relevant to brief therapy because most treatments that have been tested for efficacy—including the manualized therapies commonly used in controlled, double-blind outcome studies— are short term. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that most of the studies on psychotherapy outcomes are investigations of the effectiveness of short-term therapies. This is partly because cognitive and behavioral therapies dominate the outcome literature (Roth and Fonagy 2006), although a sizable body of studies does support the effectiveness of short-term dynamic therapy, IPT, and solution-focused brief therapy (Abbass et al. 2006; Cuipjers et al. 2008; Dewan et al. 2012; Leichsenring 2009; Markowitz and Weissman 2009).

|

Table 29-7. Structural elements common to the brief therapies |

||

|

Engagement Rapid formation of a therapeutic alliance and translation of presenting problems into focal goals Discrepancy Provision of novel skills, insights, and experiences that challenge patient patterns and facilitate new understandings and actions Consolidation Rehearsal of new patterns in varied contexts, accompanied by feedback, to ensure internalization and relapse prevention |

||

A review of duration and outcome in therapy (Steenbarger 1994) observed that this relation is complicated by several factors:

Early investigations of the dose-effect relation in psychotherapy found that approximately 50% of patients have significant improvement within 8 sessions of therapy; 75% reach such improvement within 26 sessions (Howard et al. 1986). This curvilinear relation suggests that much of therapy's effect occurs in a brief period for a large proportion of patients. It also indicates that some patients benefit from more extended treatment. Lambert and Ogles (2004), in a comprehensive review, reported that the dose-effect curve is more modestly sloped than those early findings suggested. Specifically, 50% of the patients who begin treatment at lower levels of psychological functioning reach clinically significant levels of improvement within 21 sessions (Lambert 2013). This same improvement is reached within 7 sessions among patients who begin treatment at higher levels of psychological functioning when more modest symptom change criteria are used. No single dose-effect curve describes the relation between time and change across all patients. It is safe to say, however, that if the goal of treatment is sustained functional change, most individuals meeting DSM diagnostic criteria will require more time for change than is typically afforded by the briefest treatment models.

These findings highlight the importance of patient selection in the conduct of brief therapy. The dose-effect research suggests some of the following inclusion criteria:

The listed criteria, which form the acronym DISCUS (Table 29-8), can be useful during initial interviews in determining the likelihood that treatment changes will be achieved within a brief time frame. This can be useful in settings such as community mental health centers, managed health care plans, and college and university counseling centers, which must rationally allocate scarce treatment resources to the treatment needs of a population. The criteria also suggest that firm, brief time limits on treatment for all patients are likely to prove ineffective for a significant proportion of the population. Patients with chronic, severe, and complex presenting concerns are much more likely to require extended intervention than are patients with recent, nonsevere, and simple presentations. Similarly, brief treatments are likely to be most relevant to patients with a high readiness for change and problems with low rates of relapse.

Nevertheless, brief therapy techniques may still prove useful in the conduct of ongoing psychotherapy. Cummings and Sayama (1995) made a compelling case for intermittent brief therapy throughout the life cycle, so that the benefits of focused change are blended with the benefits of longer-term assistance. Marsha Linehan's dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan 1993), which uses sequential short-term behavioral interventions in the treatment of personality disorders, illustrates one way in which brevity may be compatible with longer-term assistance. Roth and Fonagy (2006) reported that this therapy has been more effective in reducing the impulsive behaviors associated with borderline personality disorder than in changing facets such as interpersonal functioning. More research is needed to determine the promise and limits of sequential short-term interventions in the treatment of pervasive psychiatric disorders, particularly in light of findings that outcomes for many disorders are enhanced by the combination of brief therapies with psychopharmacological intervention (Thase and Jindal 2004).

|

Table 29-8. Patient selection criteria predictive of success in brief therapy (DISCUS) |

||

|

Duration of presenting problems: Brief Interpersonal functioning: Good, able to quickly form a trusting relationship Severity of presenting problems: Mild to moderate Complexity of presenting problems: Limited, circumscribed, with low relapse potential Understanding of the need for change: Ready to take action Social supports: Strong and easily accessible |

||

As mentioned earlier, a large body of research suggests that the ingredients common to the psychotherapies are more important than their specific interventions in generating clinical outcomes (Asay and Lambert 1999; Greenberg 2012; Wampold 2001). These common effective ingredients include the quality of the therapeutic relationship (Crits-Christoph et al. 2013; Lambert and Barley 2002); patient expectations, readiness for change, and capacity for attachment (Clarkin and Levy 2004; Greenberg et al. 2006); and therapist ability to engage patients in a constructive manner (Beutler et al. 2004). A vexing finding in the psychotherapy literature is that researchers who champion specific treatment approaches consistently report more favorable results from their approaches than do researchers who do not champion specific approaches (Wampold 2001). This allegiance effect likely speaks to the role of the therapist's, as well as the patient's, expectations in generating outcomes. Indeed, when outcome studies have sought to eliminate allegiance as an outcome factor and limit outcome variance to specific treatment effects by requiring strict adherence to therapy manuals, the benefits of psychotherapy were greatly reduced or eliminated (Wampold 2001).

Given these findings, the brief therapies likely achieve their results by 1) intensifying the change ingredients found among all therapies, including longer-term ones (Steenbarger 2002), and 2) limiting application of short-term methods to patient populations most likely to benefit from psychosocial interventions. Lambert and Archer (2006) reported that patients who benefited from the initial sessions of therapy were most likely to have favorable outcomes by the end of treatment and at follow-up periods. This is significant because it suggests that the course and outcome are determined before most of the procedures that distinguish the various therapeutic schools have been initiated.

Among the brief therapies, therapists' skill factors—their ability to facilitate and sustain a treatment focus and their ability to provide novel experiences for patients—may be more important than the specific methods they use (Baldwin and Imel 2013). Lambert and Archer (2006) observed that therapists who are given feedback about the progress of their poor-prognosis patients early in treatment have more favorable outcomes than do therapists who are not given feedback. This points to skill factors among therapists as potential mediators of outcome. A detailed analysis by Wampold (2001) indicated that therapist competence accounts for greater treatment variance than do specific treatments themselves. Indeed, when outcome studies assigned therapists to multiple treatments, competent therapists tended to have significantly better outcomes than did less competent ones, regardless of the treatment modality.

Finally, all this research suggests that the factors that make therapy efficient are not entirely separable from those that make therapy effective. It may not be far wrong to assert that therapy is most likely to be brief when it is performed skillfully with patients most open to, and likely to benefit from, psychosocial intervention. The skills that make for successful treatment—the ability to foster novel experiences of self and others in an emotionally charged context via the medium of a supportive alliance—appear to be equally essential to brevity.

Seeking to make psychotherapy treatment more efficient, innovative psychoanalysts originally presented the key components of brief therapy. They stressed narrowed patient inclusion criteria, narrowed treatment focus, an active therapist, a limit on time and/or number of sessions, and facilitation of corrective emotional experiences. Building on dynamic tradition, behaviorists, cognitive therapists, and strategic therapists went on to develop three broad models of brief therapy based on their understanding about the causes of presenting problems and the techniques necessary to alter them. Relational therapies, which assume that presenting symptoms are a result of problems with significant relationships, include brief psychodynamic therapies and interpersonal therapy. Learning therapies, such as behavior therapies and cognitive therapy, view symptoms as arising from maladaptive learned behavior patterns that can be unlearned. Contextual therapies place the emphasis on ways in which presenting problems are situated within—and sustained by—their psychosocial contexts. Strategic therapies and solution-focused therapy are major models of contextual therapy.

Studies find that therapy is often brief by default due to patient dropout, restricted coverage, therapeutic rupture, and so on. This chapter provides guidelines for therapies that are brief by design. Brief therapies vary from single-session approaches and very brief strategic treatments to dynamic interventions that often exceed 20 sessions. Behavioral and cognitive therapies are of intermediate duration. Manuals developed by several treatment schools have made it easier to practice these techniques with fidelity and to conduct research. Indeed, most psychotherapy research is focused on brief therapy and clearly supports the efficacy of brief therapy approaches for a broad range of patients. As a result of the growth of brief therapy models, manuals, and research evidence, in association with fiscal constraints and demonstrated positive patient outcomes, brief therapy has become the norm for the majority of today's patients.

Key Clinical Points

Abbass AA, Hancock JT, Henderson J, et al: Short term psychodynamic psychotherapies for common mental disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD004687, 2006

Alexander F, French TM: Psychoanalytic Therapy: Principles and Applications. New York, Ronald Press, 1946

Asay TP, Lambert MJ: The empirical case for the common factors in therapy: quantitative findings, in The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. Edited by Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1999, pp 33-56

Baldwin SA, Imel ZE: Therapist effects: findings and methods, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 6th Edition. Edited by Lambert MJ. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley, 2013, pp 258-297

Barlow D: Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic, 2nd Edition. New York, Guilford, 2002

Baucom DH, Epstein NB, Sullivan LJ: Brief couple therapy, in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Edited by Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012, pp 239-276

Beck AT: Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York, International Universities Press, 1976

Beck AT, Freedman A, Davis D, et al: Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders, 2nd Edition. New York, Guilford, 2004

Beck JS: Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York, Guilford, 1995

Beck JS, Bieling PJ, Grant W: Cognitive therapy, in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Edited by Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012, pp 45-81

Beutler LE, Malik M, Alimohamed S, et al: Therapist variables, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th Edition. Edited by Lambert MJ. New York, Wiley, 2004, pp 227-306

Binder JL: Key Competencies in Brief Dynamic Psychotherapy: Clinical Practice Beyond the Manual. New York, Guilford, 2010

Binder JL, Strupp HH: The Vanderbilt approach to time-limited dynamic psychotherapy, in Handbook of Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. Edited by Crits-Christoph P, Barber JP. New York, Basic Books, 1991, pp 137-165

Breuer J, Freud S: Studies in hysteria (1893-1895), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol 2. Translated and edited by Strachey J (in collaboration with Freud A). London, Hogarth, 1955, pp 1-311

Budman SH, Gurman AS: Theory and Practice of Brief Therapy. New York, Guilford, 1988

Clarkin JF, Levy KN: The influence of client variables on psychotherapy, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th Edition. Edited by Lambert MJ. New York, Wiley, 2004, pp 194-226

Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MBC, Mukherjee D: Psychotherapy process-outcome research, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 6th Edition. Edited by Lambert MJ. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley, 2013, pp 298-340

Cuipjers P, van Sraten A, Andersson G, et al: Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:909-922, 2008

Cummings N, Sayama M: Focused Psychotherapy: A Casebook of Brief, Intermittent Psychotherapy Throughout the Life Cycle. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1995

Davanloo H: Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Jason Aronson, 1980

de Shazer S: Clues: Investigating Solutions in Brief Therapy. New York, WW Norton, 1988

Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP (eds): The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012

Eisenstein S, Levy NA, Marmor J: The Dyadic Transaction: An Investigation Into the Nature of the Psychotherapeutic Process. New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction, 1994

Ellis A: Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. New York, Lyle Stuart, 1962

Erickson M, Haley J: Advanced Techniques of Hypnosis and Therapy: Selected Papers of Milton Erickson, M.D. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1967

Fisch R, Weakland JH, Segal L: The Tactics of Change. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass, 1982

Fisher S, Greenberg RP: The Scientific Credibility of Freud's Theories and Therapy. New York, Columbia University Press, 1985

Fisher S, Greenberg RP: Freud Scientifically Reappraised: Testing the Theories and Therapy. New York, Wiley, 1996

Gillihan SJ, Hembree EA, Foa EB: Behavior therapy: exposure therapy for anxiety disorders, in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Edited by Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012, pp 83-120

Gingerich WJ, Eisengart S: Solution-focused brief therapy: a review of the outcome research. Fam Process 39(4):477-498, 2000

Greenberg RP: Essential ingredients for successful psychotherapy: effect of common factors, in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Edited by Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012, pp 15-25

Greenberg RP, Constantino MJ, Bruce N: Are patient expectations still relevant for psychotherapy process and outcome? Clin Psychol Rev 26:657-678, 2006

Haley J: Strategies of Psychotherapy, 2nd Edition. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1963

Haley J: Problem-Solving Therapy. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass, 1976

Hollon SD, Beck AT: Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th Edition. Edited by Lambert MJ. New York, Wiley, 2004, pp 447-492

Howard KI, Kopta SM, Krause MJ, et al: The dose-effect relationship in psychotherapy. Am Psychol 41:159-164, 1986

Hoyt MF, Rosenbaum R, Talmon M: Planned single-session therapy, in The First Session in Brief Therapy. Edited by Bud-man SH, Hoyt MF, Friedman S. New York, Guilford, 1992, pp 59-86

Huppert JD, Fabbro A, Barlow DH: Evidence-based practice and psychological treatments, in Evidence-Based Psychotherapy: Where Practice and Research Meet. Edited by Goodheart CD, Kazdin AE, Sternberg RJ. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2006, pp 131-152

Lambert MJ: The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 6th Edition. Edited by Lambert MJ. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley, 2013, pp 169-218

Lambert MJ, Archer A: Research findings on the effects of psychotherapy and their implications for practice, in Evidence-Based Psychotherapy: Where Practice and Research Meet. Edited by Goodheart CD, Kazdin AE, Sternberg RJ. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2006, pp 111-130

Lambert MJ, Barley DE: Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome, in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients. Edited by Norcross JC. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp 17-36

Lambert MJ, Ogles BM: The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th Edition. Edited by Lambert MJ. New York, Wiley, 2004, pp 139-193

Leichsenring F: Application of psychodynamic psychotherapy to specific disorders: efficacy and indications, in Textbook of Psychotherapeutic Treatments. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009, pp 97-132

Levenson H: Time-Limited Dynamic Psychotherapy: A Guide to Clinical Practice. New York, Basic Books, 1995

Levenson H: Time-limited dynamic psychotherapy: an integrative perspective, in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Edited by Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012, pp 195-237

Levy RL, Shelton JL: Tasks in brief therapy, in Handbook of Brief Therapies. Edited by Wells RA, Giannetti VJ. New York, Plenum, 1990, pp 145-164

Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993

Luborsky L, Mark D: Short-term supportive-expressive psychoanalytic psychotherapy, in Handbook of Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. Edited by Crits-Christoph P, Barber JP. New York, Basic Books, 1991, pp 110-136

Malan DH: The Frontier of Brief Psychotherapy. New York, Plenum, 1976

Mann J: Time-Limited Psychotherapy. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1973

Markowitz JC, Weissman MM: Applications of individual interpersonal psychotherapy to specific disorders, in Textbook of Psychotherapeutic Treatments. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009, pp 339-364

O'Hanlon W, Weiner-Davis J: In Search of Solution: A New Direction in Psychotherapy. New York, WW Norton, 1989

Prochaska JO, Norcross JC: Stages of change, in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients. Edited by Norcross JC. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp 303-314

Quick EK: Doing What Works in Brief Psychotherapy, 2nd Edition. Burlington, MA, Elsevier, 2008

Ratner H, George E, Iveson C: Solution Focused Brief Therapy: 100 Key Points and Techniques. New York, Routledge, 2012

Reed GM, Eisman EJ: Uses and misuses of evidence: managed care, treatment guidelines, and outcomes measurement in professional practice, in Evidence-Based Psychotherapy: Where Practice and Research Meet. Edited by Goodheart CD, Kazdin AE, Sternberg RJ. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2006, pp 13-36

Rosenbaum R: Strategic psychotherapy, in Handbook of the Brief Psychotherapies. Edited by Wells RA, Giannetti VJ. New York, Plenum, 1990, pp 351-404

Roth A, Fonagy P: What Works for Whom? A Critical Review of Psychotherapy Research, 2nd Edition. New York, Guilford, 2006

Shapiro F: Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures, 2nd Edition. New York, Guilford, 2001

Sifneos PE: Short-Term Psychotherapy and Emotional Crisis. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1972

Skinner BF: About Behaviorism. New York, Random House, 1974

Steenbarger BN: Toward science-practice integration in brief counseling and therapy. Couns Psychol 20:403-450, 1992

Steenbarger BN: Duration and outcome in psychotherapy: an integrative review. Prof Psychol Res Pr 25:111-119, 1994

Steenbarger BN: Brief therapy, in Encyclopedia of Psychotherapy, Vol 1. Edited by Hersen M, Sledge W. New York, Elsevier, 2002, pp 349-358

Steenbarger BN: The importance of novelty in psychotherapy, in Clinical Strategies for Becoming a Master Psychotherapist. Edited by O'Donohue W, Cummings NA, Cummings JL. New York, Academic Press, 2006, pp 278-293

Steenbarger BN: Solution-focused brief therapy: doing what works, in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Edited by Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012, pp 121-155

Stuart S: Interpersonal psychotherapy, in The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Edited by Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012, pp 157-193

Stuart S, Robertson M: Interpersonal Psychotherapy: A Clinician's Guide, 2nd Edition. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, 2012

Thase ME, Jindal RD: Combining psychotherapy and psychopharmacology for treatment of mental disorders, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th Edition. Edited by Lambert MJ. New York, Wiley, 2004, pp 743-766

Wallerstein RS: Forty-Lives in Treatment: A Study of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. New York, Guilford, 1986

Wallerstein RS: The psychotherapy research project of the Menninger Foundation: an overview. J Consult Clin Psychol 57:195-205, 1989

Walter JL, Peller JE: Becoming Solution-Focused in Brief Therapy. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1992

Wampold BE: The Great Psychotherapy Debate: Models, Methods, and Findings. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 2001

Watzlawick P, Weakland H, Fisch R: Change: Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution. New York, WW Norton, 1974

Weissman MM, Markowitz JW, Klerman GL: Comprehensive Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York, Basic Books, 2000

Weissman MM, Markowitz JW, Klerman GL: Clinician's Quick Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 2007

Wolpe J: Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 1958

Wright J, Sudak D, Turkington D, et al: High-Yield Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Brief Sessions. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2010

Barlow DH: Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, 3rd Edition. New York, Guilford, 2001

Beck JS: Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York, Guilford, 2011

Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP: The Art and Science of Brief Psychotherapies: An Illustrated Guide, 2nd Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012

Levenson H: Brief Dynamic Therapy. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2010

Stuart S, Robertson M: Interpersonal Psychotherapy: A Clinician's Guide, 2nd Edition. London, Edward Arnold, 2012

Walter JL, Peller JE: Becoming Solution-Focused in Brief Therapy. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1992

Academy of Cognitive Therapy: www.acad-emyofct.org

Association of Advancement of Behavior Therapy (AABT)/Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT): www.aabt.org

International Society for Interpersonal Psychotherapy: www.interpersonalpsycho-therapy.org

Society for Psychotherapy Research: www.psychotherapyresearch.org

Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association: www.sfbta.org