CHAPTER 24

Neurocognitive Disorders

The neurocognitive disorders encompass DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000) cognitive disorders—delirium, dementia, and other cognitive disorders designated in early DSM editions as organic mental disorders. "Organic" mental disorders were conceptualized as the product of structural or physiological changes in brain tissue. By contrast, functional disorders were presumed to result from aberrations in processes that were entirely mental. It has become increasingly evident that the line between organic and functional disorders is unclear and that many "functional" disorders such as schizophrenia are in fact related to abnormalities of brain development and structure.

Until DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013), psychiatrically diagnosable conditions needed to cause "clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning" (American Psychiatric Association 2000, p. 8). However, conditions such as Alzheimer's disease usually present with mild symptoms that are minimally disabling or disruptive but that progress over time to meet the threshold of social or occupational disability (e.g., DSM-IV-TR dementia). DSM-5 recognizes this, has eliminated the term dementia, and allows categorization of the cognitive/psychiatric symptoms of brain disorders as of major or mild severity (e.g., mild neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer's disease). Another important departure from earlier nosology is the inclusion in DSM-5 of the most recent clinical criteria indicating the likelihood of a specific brain or systemic disorder causing the presenting neurocognitive disorder, using the modifiers probable or possible, the former meaning that the patient meets full criteria for a particular disorder and the latter that the patient meets only partial criteria. For example, it is now possible to make a diagnosis of major or mild neurocognitive disorder associated with probable or possible Alzheimer's disease, probable or possible frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), probable or possible Lewy body disease, and probable or possible cerebrovascular disease. Table 24-1 lists the DSM-5 neurocognitive disorders.

Based on this categorization, for example, possible Alzheimer's disease and possible vascular disease may coexist. On the other hand, a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease, vascular disease, FTLD, or Lewy body disease precludes the concomitant diagnosis of another of these diseases as probable.

Several neurocognitive disorders are often present simultaneously or serially in the same patient. Persons with major or mild neurocognitive impairment often experience delirium. Lewy body disease, vascular neurocognitive disorder, and Alzheimer's disease may be present in the same individual. In addition, psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders may coexist. Major depression may coexist with a neurocognitive disorder. Also, a neurocognitive disorder such as Alzheimer's disease may complicate schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or recurrent depression. The most common diagnostic issue in the evaluation for neurocognitive disorder is the distinction between normal aging and disease in older adults.

Vocabulary and general knowledge tend to remain stable with aging, but speed of information processing and psychomotor performance decline. Older adults tend to recall the gist of stories or events rather than the details. Aging-related changes in brain structure and function include loss of dendritic arborization and loss of neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert and septal nuclei and in the substantia nigra. Loss of cells in the first two nuclei reduces cholinergic input to the forebrain and increases the likelihood of delirium from anticholinergic drugs such as bladder or gastrointestinal relaxants. Loss of pigmented substantia nigra cells increases the sensitivity of dopamine D2 receptors and thus sensitivity to the extrapyramidal effects of antipsychotic agents.

Impairment of short-term memory is the most common age-associated cognitive complaint of older adults and the most common cause for cognitive evaluation. Approximately 4% of community-dwelling individuals ages 65-69 years and 36% of those ages 85 years and older report moderate to severe memory problems (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics 2000). Most elders report forgetting names frequently, losing objects such as keys, and forgetting telephone numbers. Older adults recall as well as younger adults the gist of material they have learned, but recall details less well. Because they rely on their general knowledge to supplement their memory, older adults are also more prone to errors in recall.

Various memory functions appear to involve different mechanisms and different brain circuitry (reviewed in Budson and Price 2005). Short-term memory is mediated by neurotransmitter-induced long-term potentiation that strengthens synaptic connections and can be disrupted by blocking the action of acetylcholine. The long-term storage of memories involves the outgrowth of new axon terminals and the development of new synapses and can be blocked by protein synthesis inhibitors. The prefrontal cortex appears to be the site of working memory—that is, the ability to manipulate small bits of information without their transfer to long-term storage. The hippocampus transfers memory from short-term to long-term storage, and the portions of the cortex that originally processed the information are the sites of long-term storage of fact-based memory (Squire 1992). Healthy elders' memory is generally preserved for personally relevant, well-learned material, but their ability to process novel information declines (Petersen et al. 1992). Slowing the presentation of new information helps normal older adults; cuing helps them retrieve more effectively from recent memory, but memory aids are less helpful when Alzheimer's disease reaches the threshold for major neurocognitive disorder.

|

Table 24-1. DSM-5 neurocognitive disorders |

||

|

Delirium Specify whether: Substance intoxication delirium Substance withdrawal delirium Medication-induced delirium Delirium due to another medical condition Delirium due to multiple etiologies Specify if: Acute, Persistent Specify if: Hyperactive, Hypoactive, Mixed level of activity Major and Mild Neurocognitive Disorders Specify whether due to: Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Lewy body disease, vascular disease, traumatic brain injury, substance/medication use, HIV infection, prion disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, another medical condition, multiple etiologies, unspecified Specify Without behavioral disturbance, With behavioral disturbance Specify current severity: Mild, Moderate, Severe |

||

Although the most common cognitive complaint of older adults is impaired recall of names and recent events, the greatest age-associated cognitive decline is in executive function, possibly related primarily to loss of synapses in the prefrontal cortex and loss of dopaminergic input to the prefrontal cortex from the corpus striatum. This decline manifests in failure to suppress interfering information, making perseverative errors, and difficulty organizing working memory, perhaps mediated by loss of dopaminergic function in the caudate nucleus and the putamen through reduction of dopamine D2 and D3 receptors and dopamine transporters (reviewed in Hedden and Gabrieli 2005). Older adults examined with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) techniques during cognitive tasks show bilateral prefrontal cortical activation, whereas younger persons show only unilateral activation, suggesting that elders compensate by recruiting more (and perhaps inappropriate) neuronal circuits (Persson et al. 2004).

Concern about cognition may be expressed by the patient, the family, or, perhaps with good fortune, an employer. Persons with neurocognitive disorders who are employed may be fired because of poor performance, with awareness of their cognitive dysfunction emerging only at a later date—too late for continued insurance coverage and disability compensation. Unfortunately, a substantial percentage of persons with Alzheimer's disease are unaware of their cognitive deficits, and persons with the behavioral variant of FTLD are invariably unaware.

Difficulties related to cognitive impairment are often dismissed by family members or physicians as normal aging. The complaint of confusion, memory loss, or poor judgment warrants active investigation, with the extent of the investigation depending on the history, physical/neurological findings, and mental status examination.

A comprehensive assessment for the presence and differential diagnosis of a neurocognitive disorder involves history taking, mental status examination, and physical and neurological examination, including relevant laboratory screening, brain imaging, and neuropsychological testing. Assessment often requires the skills and cooperation of a psychiatrist, neurologist, and neuropsychologist.

Assessment begins with history taking, which involves the patient, a knowledgeable friend or relative, and all pertinent medical information. Direct access to medical records is important because patients and lay informants often do not accurately recall medical events or the outcomes of various laboratory tests.

In addition to the elicitation of information concerning patients' cognitive abilities, evidence is sought of emotional or interpersonal contributions to the cognitive complaint, concomitants of the cognitive complaint, and its emotional or interpersonal impact. Patients' emotional responses to their mental difficulties are evaluated, and an attempt is made to determine family strengths and weaknesses. Patients' personality patterns are also considered. All of this information helps shape the plan of management, as is illustrated in the following case example:

An 81-year-old widow who lived alone in a small Texas town was brought for evaluation by her daughter and son. They reported that she had been experiencing slowly progressive memory difficulty. She was fiercely independent, had resisted strong family efforts to move her closer to them, and was angered by their insistence on a medical evaluation. Following an appropriate workup, her diagnosis was Alzheimer's disease (DSM-5 major neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer's disease). The patient disagreed. She did not see herself as handicapped, and despite neuropsychological evidence that it would be best if she did not drive and did not manage her own financial affairs, she insisted on her independence. In discussion with the family, the issue resolved to one of quality of life. What was there to be gained by restricting the mother's activities or trying to force on her the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or treatment with a cognitive enhancer? Her primary activities were driving to her small church and the grocery store, and she did not drive on highways. She was unlikely to take medication other than her familiar blood pressure pills, and there was concern that she would not take medication appropriately. The son and daughter eventually decided that their efforts to protect their mother would alienate her and that it was best to accept her decisions so as to maintain a positive relationship with her. Meanwhile, they would maintain loose supervision through frequent visits and telephone calls.

It is important for the clinician to know what medications the patient is taking and, in the case of an older adult, to request that the patient bring them, including any over-the-counter medications, to the appointment. A patient (with his or her permission) can be interviewed in the presence of a family member to ensure the accuracy of factual information and to ascertain how the patient's performance during the examination compares with his or her daily performance. A patient is interviewed alone if unaccompanied or if he or she objects to others in the examination room. When possible, time is allowed to interview the accompanying person alone, because if interviewed only with the patient present, he or she might withhold information that may humiliate or anger a patient. Typical withheld information concerns paranoid thinking, hallucinations, or incontinence.

Having a friend or relative present is a comfort to most persons with cognitive impairment. In this situation, history taking can be a three-way conversation rather than a formal interview. In the flow of the conversation, many clues emerge concerning the relationship between patients and significant others, the impact of patients on their families, and the impact of others on the patients. Husbands often resent their wives' diminished ability to maintain their household. Dependent spouses may resent being responsible for their formerly dominant spouses. In many cases, there is tension between spouses because one does not believe that the other truly cannot learn, remember, or understand. Examining one spouse in the presence of the other can also be helpful in dealing with the intact spouse's denial and in demonstrating how to deal with the other's inability to remember, plan, and cooperate.

Symptom onset over minutes or hours suggests delirium and the possibility of infectious, toxic/metabolic, drug-induced, vascular, traumatic, psychiatric, or multiple converging factors. Onset over days or weeks suggests infectious, toxic/metabolic, or neoplastic origin. Gradual decline over months to years is more typical of degenerative disorders. Dating the onset of cognitive or behavioral difficulties is often difficult. Chronic cognitive impairment may be perceived as an acute decline when a supportive spouse becomes ill or dies or may present as a delirium occurring in the course of a medical illness or following a surgical procedure.

Symptomatic improvement is often reported with brain trauma, acute vascular disorders, and acute toxic and metabolic disorders. Marked fluctuations in cognitive dysfunction over days or weeks may occur in Lewy body disease. In most neurocognitive disorders, cognitive impairment fluctuates depending on the complexity of environmental/emotional demands, fatigue, general physical health, and time of day.

Frequently reported first symptoms of a neurocognitive disorder are loss of initiative and loss of interest in the family, the surroundings, and activities that were formerly pleasurable. Individuals with impaired frontotemporal lobe function may become either apathetic or disinhibited. Suspiciousness, irritability, and depression may occur early on. Elation or grandiosity raises the possibility of neurosyphilis. Well-formed visual hallucinations often mark the onset of Lewy body disease. Visual and tactile hallucinations and illusions are common in delirium. Auditory hallucinations in persons with neurocognitive disorders tend to be of familiar persons speaking or music playing, whereas accusatory or threatening voices are more typical of schizophrenia and psychotic depression. Sleepwalking and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder may precede the onset of Parkinson's or Lewy body disease. Partial complex seizures can cause intermittent "absences." accompanied by motor stereotypy and postictal sleepiness. Grand mal seizures may point to a focal brain lesion. Diabetes, hypertension, strokes, and heart disease are risk factors for vascular cognitive impairment and may hasten the clinical manifestation of Alzheimer's disease. Acute renal or hepatic decompensation may lead to delirium. HIV seropositivity raises the possibility of viral brain pathology or an opportunistic brain infection.

Familial disorders include Huntington's and Wilson's diseases. Alzheimer's disease occurs infrequently as an autosomal dominant familial disease; about 10% of persons with FTLD have an autosomal dominant inheritance (Rohrer et al. 2009).

Many medications may impair cognition, including anticholinergic agents such as bowel and bladder relaxants, the antihistamine diphenhydramine (a frequent ingredient in over-the-counter sleep aids), benzodiazepine hypnotics and tranquilizers, barbiturates, anticonvulsants, propranolol, and cardiac glycosides. Episodes of confusion in persons with porphyria may be induced by various medications, including barbiturates and benzodiazepines.

Alcohol abuse with severe malnutrition or episodes of delirium tremens may be followed by a neurocognitive disorder. Other substances of abuse such as organic solvents may also cause neurocognitive syndromes. Environmental toxins, such as arsenic, mercury, lead, organic solvents, and organophosphate insecticides, can produce neurocognitive syndromes, but the cognitive-behavioral impairment is usually overshadowed by severe systemic symptoms.

The sudden worsening of cognitive function in persons with established neurocognitive disorders requires exploration for evidence of unremembered falls, stroke, change in dosage or type of medications, pneumonia, or urinary tract infection.

Cognitive disorders are often overlooked because persons with slowly progressive disorders often sustain their social graces until well into their illness. This is especially true with patients who are well dressed and well groomed and give appropriate social responses, as is common in Alzheimer's disease. Mental status examination is performed in the context of developing a positive relationship with patients and their families, and therefore interactions with patients probably should not begin with the physician administering a cognitive screening examination. The examination is also performed with consideration for patients' frustration tolerance and is tailored to their level of cognitive performance. For example, when it becomes obvious that the patient is not oriented to year and month, there is little point inquiring about orientation to day and date unless malingering is suspected. Each category of inquiry should be abbreviated when the patient is irritable or easily frustrated. All responses should be treated as equally valid, whether correct or not, and the patient should be praised for effort.

Attention is tested by digit span, forward and backward. Most persons with 12 years of education and clear sensorium can repeat seven digits forward and five backward. Working memory is tested by asking patients to recall three words after a 5-minute distraction. This test can be performed with objects presented verbally or, in the case of aphasic subjects, objects shown to the patient without naming them. Response to cuing is also important because it helps to distinguish retrieval deficits from failure to encode. Testing remote memory is more difficult. Patients with little formal education can be asked about events that fall within their range of interest; this is done most effectively when an accompanying person is taken aside and asked about recent events in the patient's life (e.g., birthdays and other family events) before the patient is questioned.

Routine examination of language includes assessment of articulation, fluency, comprehension, repetition, naming, reading, and the ability to write sentences. Language disfluencies include delays in word finding, paraphasias, and neologisms. Word fluency (the ability to generate a list of words for a given category), a very sensitive indicator of cognitive impairment, can be tested by asking patients to name all the animals (for example) they can think of in 1 minute. The average score for high school graduates is 18±6 (Goodglass and Kaplan 1972).

Comprehension tests begin with graded tasks, such as asking patients to point to one, two, and three objects in the room. These are followed by simple logic questions, such as "Is my cousin's mother a man or a woman?" or "When you are dressing, which do you put on first, your shirt (blouse) or your coat?"

Naming tests should include the parts of objects, such as the parts of a watch (stem, watchband, back or case, face, crystal or glass) or the parts of a shirt (cuff, sleeve, collar, pocket, buttonhole). Reading ability should be considered in the context of patients' education. Writing ability is assessed by asking patients to write a dictated sentence and then to compose a sentence of their own.

Praxis is evaluated by asking patients to imitate an action performed by the examiner, to perform simple motor acts in response to the examiner's request, and to copy a set of simple geometric figures (e.g., intersecting pentagons). A patient's drawing of a three-dimensional cube can be used to detect constructional dyspraxia in mildly impaired, well-educated persons.

Fund of information is assessed using a standard set of questions, ranging from simple to difficult, and by evaluating the responses in relation to the patient's level of education and work achievement.

Assessment of the ability to think abstractly requires consideration of the patient's education, cultural background, and native language. Impairment of abstract reasoning can be inferred from body part substitution in tests of ideomotor praxis (e.g., using one's fingers as the teeth of a comb while pretending to comb one's hair) and from inability in clock drawing to set the time at 8:20 because there is no "20" on the clock. Judgment may be estimated by asking patients questions on how they would manage certain life situations, such as "What would you do if the electric company called and told you that your last check was returned because of insufficient funds?" However, judgment is better assessed from history elicited from someone other than the patient.

Elements of the mental status examination that detect executive dysfunction include ideomotor and constructional praxis, abstract reasoning, and judgment. Executive function is also assessed by portions of the neurological examination, including the Luria three-step test (Weiner et al. 2011), go/no-go tasks, and reciprocal motor tasks (e.g., when instructed to "tap the desk twice when I tap it once, and tap once when I tap twice"). Clock drawing is another useful test of executive function. Executive dysfunction is also reflected in the patient's history, such as mistakes in social judgment (e.g., inappropriate sexual advances), and in the course of the mental status examination, such as through inappropriate handling of objects (utilization behavior), inappropriate laughter, flirtation, or inability to maintain appropriate social and physical distance from the examiner.

Physical examination may suggest a specific disease or condition. Evidence of severe malnutrition suggests avitaminosis such as thiamine deficiency. Argyll-Robertson pupils suggest neurosyphilis. Carotid bruit raises the possibility of cerebral ischemia, and atrial fibrillation presents the possibility of cerebral embolization. Gait apraxia and early urinary incontinence are associated with normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Combined dysarthria and paralysis of gaze suggest progressive supranuclear palsy. Unilateral limb apraxia suggests corticobasal ganglionic degeneration. Bradykinesia and bradyphrenia may indicate depression, early Parkinson's disease, or both. Incoordination and sensory and cranial nerve symptoms may indicate multiple sclerosis or progressive supranuclear palsy. Choreiform movements accompany Wilson's disease and Huntington's disease; myoclonic jerks accompany Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and mid- to late-stage Alzheimer's disease. Lateralized signs and symptoms suggest a possible vascular origin. Cortical release signs such as the palmomental reflex, grasp reflex, and suck and snout reflexes are nonspecific indicators of cortical damage, as are programmed motor tasks such as the Luria three-step test.

A list of laboratory studies that are potentially useful in diagnosing neurocognitive disorders is presented in Table 24-2. Although a clinician may be tempted to use fixed panels, decisions concerning laboratory studies should be based on the individual's clinical picture. Suspected drug use or abuse calls for a toxicology battery. It is especially important to detect alcohol, barbiturate, or benzodiazepine use to prevent severe withdrawal delirium. Determination of electrolyte concentrations is primarily useful in the workup for acute changes in cognition. A serological test for syphilis is often performed as a matter of routine, but it is not indicated unless the history and clinical presentation suggest exposure to syphilis or the presence of neurosyphilis. Low blood ceruloplasmin and high urinary copper content aid in the diagnosis of Wilson's disease. Folic acid and vitamin B12 levels are often done routinely, but they offer little in the absence of severe nutritional deficiency or symptoms of pernicious anemia (Warren and Weiner 2012). Lumbar puncture can yield information confirming a clinical diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, neurosyphilis, or opportunistic central nervous system infection. HIV testing is indicated given a history of sexual exposure or blood transfusion. A diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease can be confirmed by low cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid and high tau protein levels, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease can be verified by the presence of 14-3-3 protein. An abnormal electroencephalogram can help distinguish depression from dementing illnesses and can confirm the clinical suspicion of status epilepticus. Radionuclide cisternography helps to clinch the diagnosis of normal-pressure hydrocephalus.

|

Table 24-2. Laboratory aids to diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders |

||

|

General screening Complete blood count Erythrocyte sedimentation rate Liver function tests Blood urea nitrogen Creatinine Blood glucose Calcium Thyroid function tests Serological test for syphilis Folic acid Vitamin B12 Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging Additional tests and procedures Lumbar puncture Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 and tau for Alzheimer's disease 14-3-3 protein for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease HIV testing Electroencephalogram Radionuclide cisternography for normal-pressure hydrocephalus Carotid artery Doppler studies Cerebral angiography Single-photon emission computed tomography Positron emission tomography Cerebral amyloid imaging Genetic testing Presenilin 1 and 2 for dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease DNA for trinucleotide repeats in Huntington's disease Wilson's disease |

||

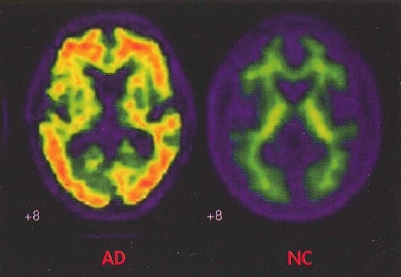

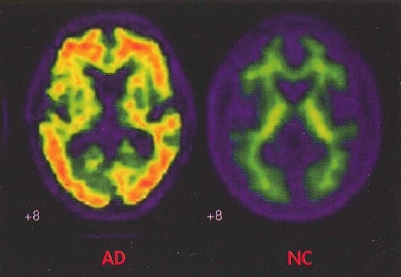

The functional brain imaging studies now in clinical use are single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). The former is used to determine patterns of regional blood flow, and the latter to determine patterns of cerebral glucose uptake. Both are used to aid in the detection of Alzheimer's disease and FTLD. SPECT has the advantage of lower cost, whereas PET has higher resolution. PET imaging of cerebral amyloid deposition with florbetapir is now used on a research basis as a marker for Alzheimer's disease (Figure 24-1). Low dopamine transporter uptake in the basal ganglia, as shown by SPECT or PET, has been incorporated as a feature suggestive of Lewy body disease.

Genetic testing can help to confirm the diagnosis of dominantly inherited familial Alzheimer's disease (mutations in presenilin 1 and 2 genes), Huntington's disease (more than 40 cytosine-adenine-guanine repeats in DNA), and Wilson's disease and can be used to ascertain risk in asymptomatic persons. Brain biopsy is useful primarily for the diagnosis of vascular inflammatory disease and is generally not indicated.

Figure 24-1. In vivo amyloid imaging.

To view this figure in color, see Plate 8 in Color Gallery in middle of book.

Florbetapir imaging (coronal view) shows no amyloid accumulation in the brain of a normal control subject (NC) and extensive accumulation in the brain of a patient with Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Source. Image courtesy of Dr. M. D. Devous, Sr.

The clinical neuropsychologist often plays an important role in several tasks: establishing the presence of a neuro-cognitive disorder, conducting the differential diagnosis, quantification of impairment, and assessment of cognitive strengths and weaknesses. Serial testing provides information on disease progression, treatment effects, or degree of recovery from brain insults such as stroke or traumatic brain injury. Table 24-3 shows typical patterns of impairment seen on neuropsychological testing of individuals with neurocognitive disorders.

|

Table 24-3. Verbal learning and memory features in neurocognitive disorders |

|||||

| Disorder | Impaired encoding | Deficient recall | intrusion errors | Perseveration errors | Impaired recognition |

|

Alzheimer's |

++ |

++ |

++ |

- |

++ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+/- |

|

Vascular |

++ |

+ |

- |

+/- |

- |

|

Depression |

+/- | +/- |

- |

- |

- |

Note. Presence (+) or absence (-) of qualitative memory features on standardized word-list learning tasks.

Source. Adapted from Cullum CM, Lacritz LH: "Neuropsychological Testing in Dementia," in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. Edited by Weiner MF, Lipton AM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009, pp. 85-104. Copyright 2009, American Psychiatric Publishing. Used with permission.

Delirium is a state of altered consciousness and cognition, usually of acute onset (hours or days) and brief duration (days or weeks). The hallmark of delirium is impaired attention. Many persons remain oriented to person, place, and time but demonstrate impairment on tests of sustained attention such as digit span and months of the year in reverse. Sleep-wake disturbances are common, as are reduced or increased psychomotor activity. Mis-identifications, illusions, and visual hallucinations are also frequent. Because of these symptoms, delirious patients are often thought by nonpsychiatric physicians to have schizophrenia, but visual hallucinations in delirium have a different quality from those of schizophrenia. They tend to be mundane and nonthreatening rather than bizarre. They often consist of animals or persons whose presence is not understood and is sometimes frightening to the patient and are not explained by an organized delusional system. Tactile hallucinations in the presence of clouded sensorium are almost invariably due to delirium. When they occur with clear sensorium, tactile hallucinations may be part of psychotic syndromes such as delusional parasitosis.

DSM-5 criteria for delirium are presented in Box 24-1; the differential diagnosis of delirium, neurocognitive disorder, and depression is presented in Table 24-4. Delirium is common in general hospital patients. In a prospective study of nonconfused individuals ages 65 years and older who were undergoing repair of hip fracture or elective hip replacement surgery, delirium was diagnosed in 20% (Duppils and Wikblad 2000). The onset of delirium was postoperative in 96% of patients and generally resolved within 48 hours. Predisposing factors were older age, cognitive impairment, and preexisting brain disease. There is also evidence that the apolipoprotein E s4 allele increases susceptibility to delirium (van Munster et al. 2009).

|

Box 24-1. DSM-5 Criteria for Delirium |

Specify whether: Substance intoxication delirium Substance withdrawal delirium Medication-induced delirium Delirium due to another medical condition Delirium due to multiple etiologies Specify if: Acute Persistent Specify if: Hyperactive Hypoactive Mixed level of activity |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

In many individuals, the first sign of a neurocognitive disorder may be postoperative delirium. Episodes of delirium frequently herald Lewy body disease. Delirium has a greater degree of personality disorganization and clouding of consciousness than mild or major neurocognitive disorder. Fluctuating cognitive ability occurs in many persons with impaired cognition but not to the extent or with the rapidity (minutes or hours) as in delirium. Persons with neurocognitive disorders usually give their best cognitive performance early in the day when they are not fatigued, and under circumstances in which they do not feel challenged or anxious. Toward the end of the day, many persons with cognitive impairment become transiently delirious, a phenomenon often referred to as sun-downing. The diagnosis of mild or major neurocognitive disorder cannot be made in the presence of delirium.

The best treatment for delirium is prevention, which means attending to the needs of vulnerable populations—that is, cognitively impaired persons with poor hearing and vision. Ideally, these vulnerable persons should be identified prior to hospitalization. For patients in long-term care facilities, cognitive impairment is the norm. Most often, consultation is requested after delirium becomes severe enough to endanger patients or to interfere with their treatment. Delirium also occurs in outpatient settings. For example, a young boy was brought in by his mother for psychiatric evaluation because of the acute onset of visual hallucinations. On the child's medication history, the mother reported the use of a topical nasal decongestant. However, an examination of the label indicated that he was actually taking atropine drops the mother had been given for treatment of an eye disorder; the hallucinations cleared soon after the medication was discontinued.

Delirium can be conceptualized as an acute failure of the brain's ability to process information. There has been much speculation in recent years concerning the pathophysiological process underlying delirium, and recent work has suggested a functional disconnection between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate gyrus (Choi et al. 2012). Although delirium has many potential causes, the most common are probably acute infections, brain trauma, and prescribed or over-the-counter medications.

There are very few medications that cannot cause delirium. Thus, in the evaluation of a patient with delirium, all drugs are suspect. The most common culprits are highly anticholinergic drugs, including over-the-counter diphenhydramine, which is often taken as a sleep aid and is not seen as a potentially toxic drug. Over-the-counter antidiarrheal drugs such as loperamide are potently anticholinergic, as are drugs commonly prescribed for overactive bladder, including tolterodine and oxybutynin. In elders, dopamine agonists or reuptake inhibitors are common causes of delirium, especially in cognitively compromised persons with Parkinson's disease.

|

Table 24-4. Differential diagnosis of delirium, neurocognitive disorder, and depression |

|||

| Delirium | Mild/major neurocognitive disorder | Depression | |

|

Sensorium |

Fluctuating consciousness |

Clear |

Clear |

|

Attention |

Markedly impaired |

Mildly to moderately impaired |

Mildly impaired |

|

Orientation |

Markedly impaired |

Mildly to moderately impaired |

Unimpaired |

|

Memory |

Globally impaired |

Recent > remote |

Unimpaired |

|

Mood (self-report) |

Fearful, apprehensive |

Usually unaffected |

Depressed |

|

Psychomotor activity |

Increased or reduced |

Normal |

Increased or reduced |

|

Hallucinations |

Visual or tactile |

Visual |

Mood-congruent auditory |

|

Delusions |

Transient, unsystematized |

Transient, unsystematized |

Mood congruent, often systematized |

|

Suicidal ideation |

Uncommon |

Uncommon |

Frequent |

|

Guilty rumination |

Absent |

Uncommon |

Frequent |

|

Sleep |

Interrupted |

Day/night confusion |

Early awakening |

|

Appetite |

Poor due to confusion |

Normal |

Reduced or increased |

Treatment of delirium is indicated in general hospital settings if the patient's delirium significantly interferes with sleep or medical treatment or causes the patient extreme fear and discomfort. Mild delirium that does not cause sleep loss, interfere with medical treatment, or lead to great fear and discomfort does not require treatment. The inpatient management of delirium is presented in Table 24-5.

There are numerous measures for helping to prevent delirium. The most important is the 24-hour presence of a person or persons with whom the patient is familiar and has a positive relationship. In addition, the accompanying person functions as an intermediary between the patient, physicians, and hospital staff, fostering accurate communication and correcting misperceptions that may occur on either side.

There are two categories of DSM-5 neurocognitive disorder: major and mild. Major neurocognitive disorder is equivalent to the earlier DSM diagnosis of dementia: an impairment of multiple cognitive abilities sufficient to interfere with self-maintenance, work, or social relationships. The diagnosis of mild neurocognitive disorder indicates that the person is able to maintain independence despite the presence of impaired cognition. The diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder is complicated by the enormous variation among individuals. Many persons who have declined cognitively may still function at a level comparable to that of an average person their own age. Therefore, clinicians must compare a person's current abilities with his or her own past abilities, usually by using retrospective accounts furnished by patients or their families and supported by simple scales of activities of daily living.

|

Table 24-5. Inpatient management of delirium |

||

|

Presume withdrawal delirium if symptoms begin 1-3 days after admission. Review use of substances with family member(s). Consider neuroleptic malignant syndrome in persons taking chronic antipsychotic drugs. Consider serotonergic syndrome in persons taking serotonin reuptake inhibitors. If possible, use personal restraint, which is preferable to mechanical restraint and is less dangerous. Ideally, arrange for a well-liked family member to be the sitter. Provide frequent physical contact (holding hand, or hand on shoulder). Assist orientation to time, place, and staff members. Provide clocks and large calendars near patient. Ensure that staff members reintroduce themselves at each visit. Keep room well lit to minimize misperceptions. Place patient in a room with a window for day/night orientation. Optimize stimulation. If television helps with reality contact, keep it on; if it agitates the patient, turn it off. Avoid benzodiazepines, except for withdrawal deliria. Return to home environment as rapidly as possible. Preferably, use oral or parenteral high-potency neuroleptics as the calming agents. Avoid administering prophylactic antiparkinson drugs. Do not administer to hyperthyroid patients. |

||

The DSM-5 criteria for major and mild neurocognitive disorder are presented in Boxes 24—2 and 24—3, respectively. Minor degrees of cognitive impairment, especially due to medications or metabolic disorders, are frequently reversible, but a full-blown major neurocognitive disorder is rarely reversible. Treatable causes of neurocognitive disorder include neurosyphilis, fungal infections, tumor, alcohol abuse, subdural hematoma, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular neurocognitive disorder. Reversible neurocognitive disorders include depression, drug toxicity, metabolic disorders, vitamin B12 deficiency, HIV-related illness, and hypothyroidism.

|

Box 24-2. DSM-5 Criteria for Major Neurocognitive Disorder |

Specify whether due to: Alzheimer's disease Frontotemporal lobar degeneration Lewy body disease Vascular disease Traumatic brain injury Substance/medication use HIV infection Prion disease Parkinson's disease Huntington's disease Another medical condition Multiple etiologies Unspecified Specify: Without behavioral disturbance With behavioral disturbance Specify current severity: Mild Moderate Severe |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

|

Box 24-3. DSM-5 Criteria for Mild Neurocognitive Disorder |

Specify whether due to: Alzheimer's disease Frontotemporal lobar degeneration Lewy body disease Vascular disease Traumatic brain injury Substance/medication use HIV infection Prion disease Parkinson's disease Huntington's disease Another medical condition Multiple etiologies Unspecified Specify: Without behavioral disturbance With behavioral disturbance |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

The commonly used term mild cognitive impairment (MCI; Petersen et al. 1997) is roughly equivalent to mild neurocognitive disorder. Individuals with MCI, as defined by Petersen and colleagues, have complaints of poor memory, normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function; show objective evidence of abnormal memory function for age; and do not meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder but are at increased risk. Many persons with MCI have early Alzheimer's disease. In fact, a postmortem study of persons with MCI diagnosed by Petersen criteria showed that all had pathological findings involving medial temporal lobe structures suggestive of evolving Alzheimer's disease (Petersen et al. 2006). Those at greatest risk for conversion to Alzheimer's disease (e.g., major neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer's disease) have severe memory impairment plus impairment in one or more other cognitive domains (Tabert et al. 2006).

The definition of MCI has been expanded to include amnestic and non-amnestic types, with the former likely progressing to Alzheimer's disease (approximately 50% over 5 years) and the latter to other neurocognitive disorders (Table 24-6). There are, however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI. The risk for progression from MCI to Alzheimer's disease is increased with the accumulation of brain amyloid detected on PET scanning and with low hippocampal volume on MRI studies (Koivunen et al. 2011).

A discussion of the many conditions that cause neurocognitive disorders is beyond the scope of this chapter but is presented in Weiner and Lipton (2009). This chapter considers the four most common causes of major neurocognitive disorders in adults: Alzheimer's disease, FTLD, Lewy body disease, and cerebrovascular disease (Table 24-7).

|

Table 24-6. Possible etiologies of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) |

||

| Amnestic MCI | Nonamnestic MCI | |

|

Single domain |

Single domain |

|

|

Alzheimer's disease |

Frontotemporal |

|

|

Depression |

||

|

Multiple domain |

Multiple domain |

|

|

Vascular |

Lewy body |

|

|

Vascular |

||

Source. Adapted from Geda YE, Negash S, Petersen RC: "Mild Cognitive Impairment," in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. Edited by Weiner MF, Lipton AM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009, pp. 173-180. Copyright 2009, American Psychiatric Publishing. Used with permission.

Alzheimer's disease is highly prevalent, occurring most commonly as the sporadic form. Its prevalence increases with age; among individuals with the disease, an estimated 4% are younger than 65 years, 13% are 65-74 years, 44% are 75-84 years, and 38% are 85 years or older (Hebert et al. 2013). In rare cases, the disease is dominantly inherited and may have onset as early as the 20s. The most commonly presumed etiology is overabundance in the brain of the dimeric form of β-amyloid 42 (Aβ42), a peptide that is derived from amyloid precursor protein by the joint action of enzymes β and γ secretase (Rosenberg 2003). This overabundance of Aβ42 may be due to overproduction (as occurs in trisomy 21 Down syndrome) or inadequate clearance from the brain and leads to the designation of Alzheimer's disease as an amyloidopathy. The two major risk factors for Alzheimer's disease are age and carriage of the s4 allele of the cholesteroltransporting molecule apolipoprotein E (Genin et al. 2011). The histopathology of the disease includes extracellular neuritic plaques with an amyloid core surrounded by dystrophic neuritis and intracellular tangles consisting of phosphorylated tau protein. This pathology usually appears first in the medial temporal lobes and later involves the parietal and frontal lobes. The clinical illness usually manifests in the late 60s or early 70s with impairment of short-term memory that may or may not be noticed by the patient. The disease most often comes to medical attention with the advent of executive impairment. It is possible to function well if one's only cognitive problem is impaired short-term memory (e.g., amnestic MCI), but not if one develops concomitant impairment of attention and other executive abilities. The course of illness is in terms of years but is highly variable, with survival up to 20 years and with life expectancy dependent on quality of nursing care. Apparent sudden onset may occur with the loss of a protective spouse or may present as a delirium during a medical or surgical hospitalization. Disease onset in the 80s with very slow progression may be the tangle-only variant of Alzheimer's disease (Yamada 2003). DSM-5 criteria for major or mild neurocognitive disorder due to probable or possible Alzheimer's disease are presented in Box 24-4.

|

Table 24-7. Diagnostic features of the most common neurocognitive disorders in adults |

||||

| Alzheimer's disease | Frontotemporal lobar degeneration | Lewy body disease | Cerebrovascular disease | |

|

Clinical onset |

Insidious |

Insidious |

Insidious to sudden |

Sudden |

|

Initial symptom |

Recent memory impairment |

Poor judgment or language impairment |

Well-formed visual hallucinations |

Related to stroke site |

|

Progression |

Insidious |

Insidious |

Fluctuating |

Stair-step |

|

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder |

No |

No |

Often precedes cognitive symptoms |

No |

|

Insight |

Variable |

None |

Good |

Good |

|

Neuropsychiatric testing |

General cortical impairment |

Executive dysfunction |

Marked visuospatial impairment |

Lateralized |

|

Computed tomography / magnetic resonance imaging findings |

Normal to global and/or hippocampal atrophy |

Frontotemporal atrophy |

Normal to global and/or hippocampal atrophy |

Cortical stroke (s) or subcortical lacunes |

|

Positron emission tomography findings |

Reduced temporoparietal and posterior cingulate metabolism |

Reduced frontotemporal metabolism |

Reduced temporoparietal and occipital metabolism |

Reduced metabolism in area of stroke(s) |

|

Cerebrospinal fluid |

Low β-amyloid42, high tau and phosphorylated tau |

Normal |

Normal, unless coincident with Alzheimer's disease |

Depends on recency of stroke |

|

Extrapyramidal signs |

Late |

In corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, multisystem degeneration |

Early unilateral resting tremor and arm rigidity |

Related to site of stroke(s) |

|

Motor/sensory signs |

None |

None |

Unilateral resting tremor |

Related to site of stroke(s) |

|

Box 24-4. DSM-5 Criteria for Major or Mild Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Alzheimer's Disease |

For major neurocognitive disorder: Probable Alzheimer's disease is diagnosed if either of the following is present; otherwise, possible Alzheimer's disease should be diagnosed. For mild neurocognitive disorder: Probable Alzheimer's disease is diagnosed if there is evidence of a causative Alzheimer's disease genetic mutation from either genetic testing or family history. Possible Alzheimer's disease is diagnosed if there is no evidence of a causative Alzheimer's disease genetic mutation from either genetic testing or family history, and all three of the following are present: |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

In addition to impaired recent memory, common additional findings on mental status examination are reduced attention, verbal fluency (naming fewer than 12 animals in a minute for persons with 12 years of education), word (noun) finding, ideational dyspraxia (e.g., when asked to "show me how you turn a key in a lock"), constructional dyspraxia (e.g., when copying a drawing of intersecting pentagons), impaired clock drawing, and impaired abstract reasoning. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in early disease tend to be apathy and depression; psychotic symptoms may occur in midstage disease. The most common symptoms are delusions of theft, but these are rarely systematized. The visual hallucinations often reported in midstage Alzheimer's disease may point to the coexistence of Lewy body pathology.

Neurological examination is initially normal in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Later in the course of the illness, myoclonus and mild extrapyramidal signs may appear, the latter due to Alzheimer's pathology in the substantia nigra. Seizures may occur late in the course of the disease. They are usually not frequent and respond well to antiepileptic drugs. Computed tomography (CT) and MRI scans of the brain in early disease are frequently normal, as are electroencephalograms, although reduced hippocampal volume and slightly enlarged ventricular temporal horns may be present. SPECT scans frequently show reduced temporoparietal blood flow; PET scans may show reduced uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose in the same regions. The finding of combined low cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 and high phosphorylated tau protein is confirmatory. Recently it has become feasible in research settings to quantify amyloid deposition in the brain with several radioligands, as seen in Figure 24-1.

FTLD is the leading cause of dementia in adults younger than age 60 years. The term frontotemporal lobar degeneration is applied to a number of disease states—including Pick's disease, corticobasal degeneration, and progressive supranuclear palsy—in which the first symptoms are behavior or language impairments. (DSM-5 criteria for major or minor neuro-cognitive disorder associated with probable or possible FTLD are presented in Box 24-5.) Some individuals have mutations in the genes for tau (leading to the term tauopathies) and progranulin proteins. Of these disorders, the most likely to come to psychiatric attention are those with predominant behavioral symptoms, the so-called behavioral variant of FTLD.

|

Box 24-5. DSM-5 Criteria for Major or Mild Frontotemporal Neurocognitive Disorder |

Probable frontotemporal neurocognitive disorder is diagnosed if either of the following is present; otherwise, possible frontotemporal neurocognitive disorder should be diagnosed:

Possible frontotemporal neurocognitive disorder is diagnosed if there is no evidence of a genetic mutation, and neuroimaging has not been performed. |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

The prototypical behavioral variant of FTLD is caused by Pick's disease and presents as personality change with progressive impairment of judgment, loss of social graces, disinhibition, stimulus boundedness, and a craving for sweets. Patients' impairment of judgment, irritability, impulsiveness, and total lack of self-awareness often leads to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

A diagnosis of language variant requires that the most prominent feature is difficulty with language, that the language impairment is the principal cause of impaired daily activities, and that aphasia is the most prominent deficit at symptom onset and for the initial stage of the disease. The language variant includes the semantic dementia variant and progressive nonfluent aphasia. Semantic dementia usually begins as a fluent dysphasia with such great difficulty in naming and in understanding that these patients at first may appear to be malingering. Their language symptoms are unrelated to the frequency of word use. In addition, patients will often be unable to describe or demonstrate the use of common objects such as door keys. Progressive nonfluent aphasia involves expressive aphasia with wordfinding difficulty, agrammatism, and phonemic paraphasias (e.g., "cluck" or "click" for clock). Often, functional or behavioral symptoms do not occur until late in the disease. A third language variant, not contained in DSM-5, has been proposed and named the logopenic/phonological variant. It is characterized by impaired single word retrieval in spontaneous speech and writing and impaired repetition of sentences and phrases.

The clinical presentation of these variants relates to the loci of brain pathology. Patients with the semantic variety have prominent anterior temporal atrophy, patients with the progressive nonfluent variety have left posterior frontoinsular atrophy, and those with the logopenic variety have left posterior perisylvian or parietal atrophy. SPECT and PET studies show corresponding areas of decreased blood flow and glucose uptake (Gorno-Tempini et al. 2011).

Criteria for the DSM-5 diagnosis of major or mild neurocognitive disorder associated with probable or possible Lewy body disease are presented in Box 24-6. Lewy bodies are round, often haloed cytoplasmic inclusions composed largely of alpha synuclein, leading to the designation of Lewy body disease as a synucleinopathy. Up to 20% of persons with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease also have numerous cortical Lewy bodies (Weiner et al. 1996). These cases were previously called the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease. Diffuse cortical Lewy body pathology without concomitant Alzheimer's pathology is rare. Often indistinguishable from Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body disease has certain key features that aid in the diagnosis. They include the sudden onset of visual hallucinations, which frequently remit and reoccur. There are marked fluctuations in sensorium, with episodes of confusion lasting days or weeks followed by relative clarity for equal periods of time. Mild parkinsonism occurs early on. REM sleep behavior disorder is a frequent concomitant and often precedes the cognitive symptoms. Functional brain imaging frequently shows low blood flow or low metabolic activity in the occipital lobes. Further confirmation of Lewy body disease is low levels of dopamine transporter in the basal ganglia as shown with SPECT or PET imaging.

|

Box 24-6. DSM-5 Criteria for Major or Mild Neurocognitive Disorder With Lewy Bodies |

For probable major or mild neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies, the individual has two core features, or one suggestive feature with one or more core features. For possible major or mild neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies, the individual has only one core feature, or one or more suggestive features. |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

There seems to be no major difference in the longevity of persons with Lewy body disease with or without concomitant Alzheimer's pathology. From a clinical standpoint, there are two important differences between Lewy body disease and Alzheimer's disease: the responsiveness of psychotic symptoms in Lewy body disease to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and the propensity for severe extrapyramidal side effects in patients with Lewy body disease taking antipsychotic agents. If disturbing psychotic symptoms are not ameliorated by cholinesterase inhibitors, quetiapine is the drug of choice, beginning with 25 mg po bid or tid; dosage is limited by quetiapine's principal side effect, which is sedation. In general, the extrapyramidal symptoms of Lewy body disease (largely, resting tremor of one or both upper extremities) do not respond to treatment with antiparkinson drugs.

DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) amnestic disorder has been subsumed in DSM-5 under major and minor neurocognitive disorder. The amnestic confabulatory disorder known as Korsakoff's syndrome is diagnosed in DSM-5 as major or mild neurocognitive disorder associated with substance abuse and results from thiamine deficiency, which is typically associated with malnutrition accompanying long-term alcohol abuse. It is often preceded by the delirium, ophthalmoplegia, and ataxia of Wernicke's encephalopathy. Persistent amnesia may result from many types of brain injury, the best known being the effects of bilateral hippocampal lesions, which impair recent memory and prevent additional storage while not impairing memories that were stored before the injury (Zola-Morgan et al. 1986).

The transient amnestic episodes that occur with short-acting benzodiazepines may confound diagnosis of other disorders. The importance of considering amnestic disorders in differential diagnosis is that they are reversible when due to drugs and partly reversible in Wernicke's encephalopathy.

Neurocognitive disorder associated with vascular disease is diagnosed when the patient has cognitive impairment with evidence on imaging, history, or clinical examination of cerebrovascular disease that is judged to be responsible for the cognitive impairment. Memory impairment, if present, is characteristically of the nonamnestic type, with impaired initial registration and recall and often with impaired remote memory. There may be focal neurological signs consistent with stroke (with or without history of stroke) and brain imaging evidence of cerebrovascular disease including multiple large vessel infarcts or a single strategically placed infarct (angular gyrus, thalamus, basal forebrain, or anterior or posterior communicating territories), as well as multiple basal ganglia and white matter lacunes, extensive periventricular white matter lesions, or combinations of these. DSM-5 criteria for major or mild neurocognitive disorder associated with probable or possible vascular disease are presented in Box 24-7.

|

Box 24-7. DSM-5 Criteria for Major or Mild Vascular Neurocognitive Disorder |

Probable vascular neurocognitive disorder is diagnosed if one of the following is present; otherwise possible vascular neurocognitive disorder should be diagnosed:

Possible vascular neurocognitive disorder is diagnosed if the clinical criteria are met but neuroimaging is not available and the temporal relationship of the neurocognitive syndrome with one or more cerebrovascular events is not established. |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

Other DSM-5 categories of neurocognitive disorders include those due to traumatic brain injury, substance or medication use, HIV infection, prion disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, another medical condition, or multiple etiologies, as well as unspecified neurocognitive disorder (see Table 24-1).

A diagnosis that is on the increase in young and middle-aged adults is neurocognitive disorder associated with traumatic brain injury (TBI), with neurocognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms dependent on the location and severity of trauma. Advances in the treatment of head wounds have led to a substantial increase in TBI survivors after both closed and open head injuries, with outcomes ranging from complete recovery to major neurocognitive disorder (Bigler 2009).

A common cause of mild neurocognitive disorder is postoperative cognitive dysfunction, which usually clears by 3 months after surgery, but many persons still report cognitive deficits after 6 months (Dijkstra et al. 1999). It appears that the length and type of anesthesia (e.g., local vs. general) maybe less important than factors such as intraoperative embolization (Purandare et al. 2011).

Still another major neurocognitive disorder, the senile squalor syndrome, consists of self-neglect or neglect of one's surroundings accompanied by hoarding and social isolation (Snowdon et al. 2007). The place of residence is disorganized, dirty, and filled with useless objects or materials. The exterior of the residence is usually dilapidated as well. At times, numerous animals described as "pets" are also in the dwelling and not well cared for. Attempts have been made to understand this phenomenon in terms of psychiatric disorders such as obsessive-compulsive personality disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder, but most older individuals with this set of behaviors functioned well earlier in life. It seems likely that these individuals have significant deficits in frontal brain circuitry that are variable in origin, but this has not been well studied because these individuals characteristically see themselves as having no problem and refuse examination.

In an evaluation of a person with a cognitive complaint, depression must be considered as the cause or as an aggravating factor. Many depressed persons experience cognitive impairment, although the severity of their impairment does not correlate with the severity of their depressive symptoms. Persistent deficits in cognitive function often follow remission of depressive symptoms (Nebes et al. 2003), including deficits in working memory, speed of information processing, episodic memory, and attention. The symptoms may also indicate only partial resolution of the depressive episode and may call for more aggressive antidepressant treatment. The response of both depressive and cognitive symptoms to antidepressant treatment does not firmly establish patients' sole diagnosis as depression; many older adults will develop a dementing illness (Alexopoulos et al. 1993).

The level and frequency of depressive comorbidity with Alzheimer's disease is highly controversial, partly due to the similarity between the symptoms of each illness. There is, however, an approximately 20% prevalence of major depression in the first 2 years after stroke (Robinson 2003), and depression is also frequent in Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease.

Cognitive impairment of depression has the following characteristics that differentiate it from cognitive impairment due to degenerative or metabolic brain disorder (see also Table 24-4):

CT or MRI scans are not usually helpful in differentiating depression from a neurocognitive disorder without neurological signs, but functional techniques such as PET and SPECT are useful when there are signs characteristic of a disorder such as Alzheimer's or Pick's disease. Neuropsychological testing can help in distinguishing between mood and neurocognitive disorders and in detecting comorbid mood or neurocognitive disorder, in addition to characterizing and quantifying cognitive deficits such as memory and executive function.

General medical conditions may exaggerate preexisting personality traits or cause a change in personality. There are many patterns, but emotional instability, recurrent outbursts of aggression or rage, impaired social judgment, apathy, suspiciousness, and paranoid ideation are frequent. Encephalitis, brain tumors, head trauma, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal degenerative diseases, and strokes are common causes of personality changes, which also may occur as interictal phenomena in temporal lobe epilepsy. Persons with Down syndrome who live more than 35 years demonstrate the microscopic pathology of Alzheimer's disease, but not all develop dementia (Oliver et al. 1998). It is important in this population, as in all others, to seek remediable causes of functional decline.

Speech and language are affected in many neurocognitive disorders. Speech tends to be slow in diseases of the basal ganglia, Parkinson's disease, and cerebrovascular disease; explosive or slurred in progressive supranuclear palsy; and poorly articulated in multiple sclerosis or following stroke. Disorders of language (aphasias) often result from regional brain damage and are often confused with more generalized neurocognitive disorder. Patients with aphasia usually have had a brain insult, most often stroke or head trauma. There are usually neurological deficits such as hemiparesis (especially in the Broca's type of aphasia), unilateral hyperreflexia, and visual field defects. In general, anomia that progresses to aphasia suggests neurodegenerative disease; aphasia that resolves over time to anomia generally results from acute brain injury.

The categorization of aphasias is based on the language functions they impair. Global aphasia impairs all language functions and occurs in large left-hemisphere strokes. Anomic aphasia, by contrast, primarily affects word finding, may be related to lesions of the left angular or left posterior middle temporal gyrus, and is common in Alzheimer's disease. Broca's (anterior, nonfluent) aphasia impairs verbal fluency, repetition, and naming and results from lesions of the posterior inferior portion of the left (or dominant) frontal lobe. In Broca's aphasia, speech requires great effort and is agrammatical, with omission of word modifiers such as articles, prepositions, and conjunctions. For example, a person who wants to go to a particular place, such as a restaurant, might say, "Want ... go ... you know ... eat ... " with great effort and great relief after having expressed himself or herself. These patients generally understand what is said to them and can obey commands but have difficulty with repetition, reading aloud, and writing. Although they have difficulty with naming, they are helped by prompts.

Patients with Wernicke's (posterior, fluent) aphasia have fluent (e.g., good flow of speech), paraphasic, and neologistic speech with poor comprehension, repetition, and naming. The naming difficulty is not usually aided by prompting. Reading and writing are also impaired. Speech tends to convey little information and consists of indefinite words and phrases. Word approximations (paraphasias) may be based on similar sounds, such as "meek" for "meat," or on similar meanings, such as "writer" for "pencil." The brain damage in this syndrome is to the posterior superior portion of the first temporal gyrus of the dominant hemisphere.

Neurocognitive disorders can be classified by their molecular pathology, with Alzheimer's disease classified as an amyloidopathy; Pick's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration as abnormalities of the protein tau (tauopathies); and dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease, and multisystem atrophy as abnormalities of the protein synuclein (synucleinopathies). Recently, many cases of frontotemporal dementia have been identified as progranulinopathies caused by mutations in the progranulin gene (Ward and Miller 2011). All of these molecular characterizations are limited in utility because many of these disorders have abnormalities in multiple proteins, and some proteins are affected in more than one disorder. For example, Alzheimer's disease is a mixed amyloidopathy and tauopathy.

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al. 1975), the most widely used brief screening tool for cognitive impairment, requires 10-15 minutes to administer. A perfect score is 30 points. The MMSE is confounded by premorbid intelligence and education. The originators indicate that a score of 23 or below by a person with a high school education is suggestive of a major neurocognitive disorder, whereas the cutoff score is 18 or below for a person with an eighth-grade education or less. Crum et al. (1993) published a table with suggested normal values in relation to age and education. The MMSE is protected by copyright and must be ordered from Psychological Assessment Resources (www4.parinc.com).

The Clock-Drawing Task is a simple means to detect executive dysfunction because it involves planning, sequencing, and abstract reasoning (Nolan and Mohs 1994). The subject is presented with a blank page and asked to draw the face of a clock and to place the numbers in the correct positions. After drawing a circle and placing the numbers, the subject is asked to draw in the hands indicating the time as 20 minutes after 8 o'clock. Scoring is 1 point for drawing a closed circle, 1 point for placing numbers correctly, 1 point for including all correct numbers, and 1 point for placing the hands in the correct positions. A score of less than 4 raises the suspicion of executive impairment.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Nasreddine et al. 2005) was designed to detect mild cognitive impairment (e.g., mild neurocognitive disorder). It requires about 15 minutes to administer. It samples executive function in addition to other cognitive domains. The score range is 0-30 (with a suggested cutoff of <27 points for detection of mild neurocognitive disorder). Population-based norms developed for this instrument suggest that a more appropriate cutoff score in the United States is 23 points (Rossetti et al. 2011). The instrument is available at no cost from the author at www.mocatest.org.

The most commonly used measure of psychiatric symptoms in persons with major neurocognitive disorder is the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (Cummings et al. 1994), a brief instrument that is administered to a person who knows the patient well. Other scales for quantifying noncognitive aspects of dementia may be found in Burns et al. (2004).

Treatment of Alzheimer's disease with selegiline, estrogen, prednisone, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, statins, rosiglitazone, chelating agents, and the naturally occurring substances huperzine and Ginkgo biloba has not been successful in slowing cognitive deterioration. Treatments addressing the amyloid-related pathology have been successful in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease but have proved too toxic or ineffective in humans; these treatments include active and passive immunization against Aβ42(the toxic product of abnormal amyloid precursor protein processing) and inhibitors of γ secretase, the enzyme co-responsible with β secretase for abnormal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. These and a number of other strategies are currently being pursued, including use of the naturally occurring antioxidants cur-cumin and resveratrol and of intranasal insulin. Several treatments directed at tau protein are now in progress.

A number of palliative/symptomatic drug treatments are used to enhance cognition in neurocognitive disorders. They include cholinesterase inhibitors, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, vitamin E, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and stimulants. There is little evidence of a salutary drug treatment effect on cognition after TBI.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have been used with some success in patients with Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body disease, and cognitive impairment associated with vascular disease. Results in the treatment of TBI are not clear. Patients with Alzheimer's disease have deficient cholinergic input to the neocortex; persons with Lewy body disease have even greater cholinergic deficits. Individuals with vascular dementia often have a component of Alzheimer's disease. Cholinesterase inhibitors have modest effects on cognition in these disorders but may reduce or eliminate visual hallucinations in Lewy body disease. Most commonly, patients and caregivers report increased attention and comprehension. This class of drugs, which also enhances cognition in persons without brain disease, raises baseline cognitive performance but does not slow the rate of decline. All cholinesterase inhibitors are available in once-a-day preparations. Donepezil and galantamine are administered orally; rivastigmine is characteristically used as a patch. Both donepezil and rivastigmine have been marketed as high-dose preparations for moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Dosing is presented in Table 24-8. Side effects of these drugs are dose related and include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps (from nicotinic effects), and postural hypotension and syncope due to bradycardia. A resting pulse below 50 and severe bronchopulmonary disease are relative contraindications, but the treatment decision should be made on a case-by-case basis. Many athletic individuals with a resting pulse in the 40s tolerate cholinesterase inhibitors well.

Memantine theoretically blocks the action of NMDA-type glutamate receptors, improving synaptic transmission and/or preventing calcium release that may provide neuroprotection. Memantine is well absorbed and has a 70-hour or greater half-life but is given twice per day because that was the dosage scheme used in the studies establishing efficacy. Memantine has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Dosing starts at 5 mg qd and is titrated up 5 mg qd weekly to a final dosage of 10 mg bid. There may be transient confusion or sedation during the titration phase, but memantine generally has had few adverse effects. Although widely used in patients with early Alzheimer's disease, there are no convincing efficacy data.

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine have different mechanisms of action; thus, combination therapy could, in theory, confer additional benefits (Tariot et al. 2004). This combination has become the preferred treatment in clinical practice for patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease; however, recent evidence suggests that the addition of memantine to a cholinesterase inhibitor adds little to therapeutic efficacy (Howard et al. 2012).

Vitamin E dosages of 2,000 IU qd have been associated with a small but significant slowing of functional progression of Alzheimer's disease but no improvement in cognition. This treatment, once in wide use, is now less frequently used because of an association of increased cardiovascular events with the use of high-dose vitamin E. Easy bleeding is a common side effect at this dosage but occurs infrequently at 800-1,000 IU qd.

|

Table 24-8. Dosages of commonly used cholinesterase inhibitors |

||||

| Generic name | Trade name | Initial dosage | Final dosage | Instructions |

|

Donepezil |

Aricept |

5 mg |

10-23a mg |

Every morning |

|

Rivastigmine |

Exelon patch |

4.6 mg |

9.5-13.3b mg |

Every morning |

|

Galantamine |

Razadyne extended release |

8 mg |

24 mg |

Every morning with food |

Note. Four weeks should be allowed between dosage escalations.

a Use only if patient can tolerate donepezil 10 mg/day or equivalent.

b Use only if patient can tolerate rivastigmine 9.5 mg/day or equivalent.

Persons with any neurocognitive disorder may develop delirium, paranoid psychosis, or depression, all of which can be treated in the same manner as in persons without dementia. For example, electroconvulsive therapy can be used to treat severe depression. As expected, the cognitive side effects of such therapy are more severe for persons with dementia than for cognitively intact persons, but such effects do not represent an absolute contraindication.

An important part of treatment involves managing the behavioral and emotional symptoms of neurocognitive disorders, including psychosis, depression, apathy, aggression and violence, and inappropriate sexuality. Ideally, behavioral symptoms are addressed first by modifying the behavior of the caregiver or reducing environmental triggers. Caregivers, for example, can be trained to fill in for patients' defective memory rather than asking the patients to remember. They can be trained to answer repetitive questions directly rather than saying, "I already told you that." They can avoid violence by easing patients into frightening activities such as showering or bathing instead of trying to force them. The level of noise or interpersonal stimulation in the environment can be reduced. Caregivers can deal with apathy by initiating activities. Family caregivers can learn much from dementia support groups, the many publications, and the wealth of Internet-based information that is available, for example, from the Alzheimer's Association, the Lewy Body Dementia Association, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, and the Brain Injury Association of America. Many times, however, rather than increasing demands on exhausted caregivers, medication is the treatment of choice.

No drug treatment has received FDA approval for any of the behavioral and emotional symptoms (except major depression and mania) that may arise during the course of a neurocognitive disorder. Pharmacological treatments that have been employed include antipsychotic agents, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antimanic drugs, benzodiazepines, cholinesterase inhibitors, anticonvulsants, stimulants (for treatment of apathy), β-adrenergic blockers for severe physical violence, and testosterone antagonists for aggression and sexual disinhibition in men. Drug dosages presented in this chapter are those appropriate for elders. Because virtually all drugs used to treat behavioral disturbances in persons with neurocognitive disorders are administered off label, the general guideline for younger adults is to escalate dosage until the behavior is controlled or until untoward side effects occur. See Chapter 27 in this volume, "Psychopharmacology," for recommended adult dosages of psychotropic drugs.