CHAPTER 14

Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

Across the age spectrum, trauma- and stressor-related disorders represent long-lasting suffering and functional impairment for many but also offer opportunity for helpful diagnosis, early intervention, and therapeutic benefit. These disorders, and the individuals and families affected by them, have been the subject of intensive research at every level—from epidemiological and clinical to translational, neurobiological, and neuropsychological. In this chapter we address the rapidly expanding, complex body of knowledge accumulated from this research and present several different models for understanding trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

Although some of the historic impetus for understanding and treating the effects of psychological trauma—such as the timing in 1980 of the first inclusion of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association 1980)—derives from military psychiatry, much impetus came from recognition of the traumatic impacts of genocide, child abuse, and the rape of women, and of the psychological effects of other injury or violence in the general population.

Several seminal writings set the stage for understanding child and adult PTSD and developing treatments. Following the Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston in 1942, Stanley Cobb, Erich Lindemann, and Alexandra Adler described symptoms, syndromes, and treatments after burn trauma and effects on grieving loved ones that are now embedded in the understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of PTSD, as well as in psychiatric responses to disasters (Adler 1943; Cobb and Lindemann 1943; Lindemann 1944). In his study of survivors of Hiroshima, Robert Lifton (1967) describes the horror of atomic weapons and the lasting trauma on survivors. Lenore Terr's (1979) clinical observations and study of the children of Chowchilla who were kidnapped on a school bus has provided lasting insights into the impact of trauma on development and informed the understanding of PTSD in children. In Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence: From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, Judith Herman (1992) provided direction in the psychotherapy of victims of violence and trauma, especially women. Jonathan Shay's Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character (Shay 1994) and Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming (Shay 2002) stand out as elegant literary works, informed by Homer's The Iliad and The Odyssey, that place into a historical context the traumas endured by U.S. soldiers in Vietnam and after their return home.

The chapter on trauma- and stressor-related disorders is one of the new chapters in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013). This is a timely, evidence-based revision that reflects both the enormous growth in basic and clinical research on trauma- and stressor-related disorders and these disorders' broad prevalence across the age span and across cultures. The new chapter includes disorders in which exposure to a traumatic or stressful event is listed explicitly as a diagnostic criterion (PTSD, acute stress disorder, and adjustment disorders) as well as disorders that are etiologically linked to early social neglect (reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder). Finally, attention is given to other trauma- and stressor-related conditions that did not meet full criteria for inclusion as a disorder in this diagnostic class, such as persistent complex bereavement disorder (also included in DSM-5 Section III as a condition for further study).

The DSM-5 authors made the decision to create a new chapter for the trauma-and stressor-related disorders after careful scientific review to differentiate those disorders related to a trauma or stressful event from anxiety disorders, which do not require such exposure (although some types of anxiety disorders and depressive disorders may be triggered by trauma or stressors). The specific placement of the trauma- and stressor-related disorders chapter within the DSM-5 metastructure reflects the close relationship between these disorders and the anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, which are addressed in the two preceding DSM-5 chapters, and the dissociative disorders, which are addressed in the following chapter.

In examining the epidemiological data on trauma- and stressor-related disorders, it must be recognized that incidence and prevalence vary depending on the criteria used. We include available data on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, earlier DSM criteria, and other criteria, such as those in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The World Health Organization (2002) is a primary source of epidemiological data.

Psychological trauma and stress may occur in individuals who have experienced events resulting in emotional or psychological impact (e.g., witnessing abuse), events causing both psychological and physical trauma (e.g., fires), and physical trauma with delayed psychological impact (e.g., traumatic brain injury). The trauma and stress may be simple, resulting from a single episode (e.g., a single rape, a motor vehicle accident), or may be continuous or complex, occurring over time (e.g., refugee trauma, a severe burn and extended hospital treatment, chronic child or elder abuse).

Estimates of the lifetime prevalence of trauma exposure in North America have ranged from 39% to 74% (Grinker and Spiegel 1945; Kessler et al. 1995; Resnick et al. 1993); these prevalence rates have reportedly been higher than those in Western European countries (e.g., see Hepp et al. 2006). These differences might be explained by real differences in trauma exposure across countries and cultures but might also be attributable to differences in the demographics of the studied populations (Breslau 2001) and in the methods of measuring or defining traumatic events (Solomon and Davidson 1997). Finally, there can be cultural variations in the expression of trauma-related stress disorders, although PTSD has generally been found to be valid as a diagnosis across cultures (e.g., see Hinton and Lewis-Fernandez 2011). Certain populations are especially at risk following traumatic events, as discussed in the following subsections.

Children and adolescents are at major risk following traumatic events. Preschool children are wholly dependent on parents and guardians for their wellbeing and therefore are especially vulnerable. Common traumas affecting young children and adolescents include emotional and physical abuse, accidents, and the effects of war and disasters. In DSM-5, their developmental vulnerability is reflected in six trauma- and stressor-related conditions applying to children: reactive attachment disorder, disinhibited social engagement disorder, acute stress disorder, adjustment disorder, and PTSD (including the new subtype PTSD in children ages 6 years and younger).

As in adults, the prevalence of psychological trauma and stress in children and adolescents may be underreported (J.A. Cohen and Scheeringa 2009). In studies of PTSD incidence among child survivors of specific disasters, rates of 30%-60% have been reported; and community studies in the United States consistently indicate that about 40% of high school students have witnessed or experienced trauma or violence, with about 3%-6% of those meeting PTSD criteria (Kaminer et al. 2005). Complex PTSD due to child maltreatment remains an area of active research but is not categorized as a distinct condition in DSM-5 (Resick et al. 2012).

Compared with men, women have a twofold greater overall risk of developing PTSD; the lifetime prevalence is estimated to be 8%-10% in women, versus 4%-5% in men (Kessler et al. 1995; Pietrzak et al. 2011). Potential explanations for this discrepancy include differences in trauma exposure prevalence and types of trauma, such as greater exposure to assaultive violence and rape (Breslau and Anthony 2007). The traumas that impair women's functioning also undermine their capacity to care for their dependent children, compounding the impact of PTSD in mothers. Some research suggests that gender plays less of a role when exposure levels are high, such as in military combat, but those individuals exposed to combat have predominantly been men (Woodhead et al. 2012). Recent research examining potential differences in gender-based biological risk factors (e.g., estrogen) is ongoing (e.g., Glover et al. 2012; Ressler et al. 2011).

DSM-5 Criterion A for PTSD requires exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. Although the presence of a life-threatening medical condition may not always be a Criterion A-qualifying event, many acute medical experiences qualify, such as those involving sudden or catastrophic events. Nonetheless, increasing data suggest that PTSD symptoms affect many medical and surgical patients, including those with cancer or stroke (Letamendia et al. 2012), as well as children and adults with injuries, burns, or life-threatening illnesses (Davydow et al. 2008; Stoddard and Saxe 2001). PTSD has been reported to affect seriously injured soldiers at a rate of 12% (Grieger et al. 2006), and rates of PTSD are higher among service members with penetrating trauma (13%), blunt trauma (29%), or combination injuries (33%) (McLay et al. 2012).

Elderly persons are at major risk of trauma- and stress-related disorders and are a relatively neglected, highly vulnerable, and growing population. Epidemiological studies of trauma in the elderly are at a relatively early stage. Frailty and impaired cognition may subject elderly persons to both psychological and physical neglect and abuse, a situation made more severe and life-threatening in crises such as poverty, disaster, and war (Sakauye et al. 2009).

The military populations of the United States and its allies may be the most systematically studied regarding traumatic stressors, including combat-related stress, combat injury stress, and military sexual trauma. Epidemiological studies of soldiers have documented the importance of genetic factors, childhood trauma, proximity to event(s), and multiple deployments. Studies of PTSD in the U.S. military include studies of the neurobiology, epidemiology, and treatment of PTSD. Internationally, the epidemiology of PTSD and other disorders in military populations informs the need for resources dedicated to care of those in the armed services, veterans, and their families.

A study of 2,530 U.S. soldiers from Iraq and 3,671 U.S. soldiers from Afghanistan revealed PTSD rates of 6.2%-12.2% (Hoge et al. 2004). A survey from 2004 to 2007 of 18,305 U.S. Army soldiers, from both "Active Component" and National Guard teams, following combat exposure found rates of PTSD, based on DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria and assessed with the PTSD Checklist, of 5.6%-11.3% with a high-specificity cutoff score and 20.7%-30.5% with a broad definition. Rates of depression, based on DSM-IV criteria and assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire, were 11.5%-16.0% with no functional impairment and 5.0%-8.5% with serious functional impairment. When prevalence of either PTSD or depression was assessed, the rates were even higher (Thomas et al. 2010). In the Millennium Cohort Study of 17,481 women in the U.S. military, those who were deployed had an increased risk of mental health conditions, including PTSD (Seelig et al. 2012).

Disaster survivors, including civilian war survivors of all ages, are at increased risk of traumatic stress and grief, depending on the event's duration, proximity to, and impact on the community. Despite the many thousands of civilians affected by the Asian tsunami, the earthquake in Haiti, and wars in Africa, Iraq, and Afghanistan, these survivors have been little studied. Nevertheless, the available epidemiological studies indicate increased vulnerability as a result of having limited predisaster resources and devastating and lasting psychological effects as a result of experiencing separation from loved ones; witnessing death or injury; being abused, injured, or disabled; or becoming a refugee (de Jong 2011; Stoddard et al. 2011a).

The effects of genocide on Holocaust survivors in Europe and their families led the United Nations in 1948 to adopt the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, seeking to prevent genocide and other violations of human rights (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights 1948). Although the United Nations has since been unsuccessful in preventing genocide in Cambodia, South Africa, Rwanda, Bosnia, Darfur, and elsewhere, international efforts continue. In the hope of preventing and reducing the devastating psychological impact of genocide, there is ongoing research on the long-term effects on survivors of the traumas of genocide (M.H. Cohen et al. 2009; Marshall et al. 2005; Sagi-Schwartz et al. 2003).

Greater attention to the identification and treatment of PTSD among individuals with severe mental illnesses is needed (Grubaugh et al. 2011). One study of a racially and ethnically diverse population with severe mental illnesses reported trauma exposure rates as high as 89%, with 41% of subjects meeting criteria for PTSD, which contributed to substantially poorer functioning (Subica et al. 2012). Patients with intellectual or developmental disabilities, schizophrenia, affective disorders, or other mental illnesses are vulnerable to a range of stressors, made worse in disasters if they lose access to their medications or mental health services. Traumatic stress is an important factor in the etiology of mental illnesses other than PTSD, such as borderline personality disorder. Individuals who abuse substances are also at high risk of PTSD, because substances, particularly alcohol, are involved in over half of serious physical traumas (especially serious injuries from motor vehicle accidents, sports injuries, and adult burns) and psychological traumas (e.g., from psychological abuse and rape).

The symptoms and sequelae of traumatic stress vary across the life span, with the effects being more long lasting the younger the person. Different stages of psychological and neurobiological development render an individual subject to differing impacts of stress on emotion, cognitive processing, memory, motor and sensory function, neural and synaptic growth, gene expression, and more or less healthy or pathological outcomes. While seeking to capture some of this complexity, DSM-5 is but one step in the ongoing quest to improve categorization of the complex effects of trauma and stress on the human organism.

The psychological theories applied to trauma and PTSD have derived primarily from learning theory-based treatment and research with rape victims and Vietnam veterans. According to Resick and Calhoun (2001), Mowrer's (1947) two-factor theory of classical and operant conditioning was proposed to explain posttraumatic symptoms. The first factor, classical conditioning, was applied to explain the fear and distress in survivors of trauma and led to behavior therapy techniques such as systematic desensitization and stress inoculation training. The second factor, operant conditioning, was applied to explain the development and persistence of PTSD-related avoidance symptoms and fear.

Foa et al. (1989), utilizing Lang's (1977) emotional processing theory of anxiety development, suggested that a "fear network" forms in memory that elicits escape and avoidance behavior. Based on this theory, Foa et al. (1991) reported their classic controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for rape survivors. In contrast, Horowitz (1986) proposed social-cognitive theories that moved from psychodynamic to cognitive processing perspectives. He applied these theories to treatment aimed at resolving the conflict between the need to integrate the experience and the wish to avoid intrusive reexperiencing. Developmental psychology utilizes some of these perspectives and describes the development after trauma in cognitive, affective, interpersonal, and behavioral domains from infancy through adulthood. Neuropsychology is elucidating PTSD in relation to neurocircuits, behavior, and genetics, making an effort to define relationships between the brain and posttraumatic behavior.

Ultimately, the impact of an environmental event, even a psychological one, must be understood at organic, cellular, and molecular levels. Over the past three decades, the growth of the biological PTSD literature has been explosive (Pitman et al. 2012). Discoveries of biological abnormalities in PTSD have helped to counteract skepticism regarding a disorder that is largely based on self-report and to promote its now widespread acceptance.

One of the earliest and best replicated PTSD findings is heightened autonomic (heart rate, skin conductance) and facial electromyographic reactivity to external trauma-related stimuli, such as combat sounds and film clips, as well as to internal mental imagery of the traumatic event. These findings have been interpreted within a framework of Pavlovian conditioning, in which the traumatic event serves as the unconditioned stimulus, the emotional response to it serves as the unconditioned response, trauma-related cues serve as conditioned stimuli, and the physiological reactions serve as conditioned responses. Subjects with PTSD have also been found to show heightened electromyographic responses and more consistently elevated autonomic responses to startling stimuli (Pole 2007). Elevated startle responses suggest sensitization of the nervous system.

Structural neuroimaging studies have revealed diminished volumes of the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex in persons with PTSD (Karl et al. 2006). Debate continues over whether these differences represent preexisting vulnerability factors, are the result of traumatic neurotoxicity, or both. Identical twin research has informed this debate (Gilbertson et al. 2002). Although psychological trauma no doubt changes the brain, it is premature to conclude that the brain becomes damaged. Results of functional neuroimaging studies suggest that the amygdala and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex are hyperresponsive in PTSD; this hyperresponsivity may underlie the increased fearfulness found in this disorder. The most replicated functional neuroimaging abnormality in PTSD has been hyporesponsivity of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). A current neurocircuitry model of PTSD posits that the vmPFC fails to inhibit the amygdala. Diminished vmPFC activity may also underlie the impaired extinction of conditioned fear found in PTSD, which may make it difficult to recover from the effects of trauma (Hughes and Shin 2011; Pitman et al. 2012).

The mobilization of stress hormones, including epinephrine, cortisol, and neuroactive peptides, by strong emotion enhances memory consolidation (McIntyre et al. 2012). This provides a pathogenic link between the acute response to the traumatic event and the formation of intense, durable traumatic memories, which are a cardinal feature of PTSD. Substantial research has supported sympathetic over(re)activity in PTSD (South-wick et al. 1999). A surprising finding has been that cortisol is not consistently elevated in PTSD, as might be expected according to a classical stress model. This appears to be due to hypersensitivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to negative feedback (Yehuda 2002). Levels of the neuroactive steroids allopregnanolone and pregnanolone, which confer anxiolytic and neuroprotective effects, have been found to be negatively related to PTSD reexperiencing and depressive symptoms (Rasmusson et al. 2006). Neuropeptide Y, which is co-released with norepinephrine during sympathetic activation, has been found to confer resilience.

Genetic factors account for one-third or more of the vulnerability to PTSD (Stein et al. 2002). The risk of exposure to traumatic events also has substantial genetic determination, probably mediated through inherited personality traits. The genes that increase PTSD risk are not selective, in that they typically also confer risk for other mental disorders such as anxiety disorders and depression. As with other mental disorders, genetic liability to PTSD likely involves the contributions of numerous alleles of small effect, complicating identification of selected target genes for potential preventive or therapeutic intervention. Further complicating matters, the same gene may confer either risk or resilience depending on such factors as prevalent community crime and unemployment rates (Koenen et al. 2009), illustrating that genes do not act in isolation but rather interact with the environment to produce their effects. PTSD itself represents an epitome of this interaction. An exciting frontier of PTSD research is epigenesis, which is the ability of the environment to turn the genome on or off by modifying not the DNA sequence itself but rather its transcription (expression) through the macromolecular mechanisms of DNA methylation and histone deacetylation. Epigenetic effects of traumatic exposure may lie at the heart of PTSD's pathogenesis and may account for trauma's durable effects.

PTSD is a broad-brush diagnosis that, while identifying a certain group of impaired individuals, may not address comorbidities of traumatic stress that affect human development, including depression, learning disabilities, oppositional and conduct disorders, traumatic bereavement, substance abuse, and adult conditions that are strongly associated with prior traumatization, the effects of which often do not meet criteria for PTSD. For instance, growing evidence supports childhood trauma as a risk factor for poorer stress tolerance, difficulties with emotion regulation, and elevated incidence and severity of a range of psychiatric conditions.

The DSM-IV childhood diagnosis reactive attachment disorder (RAD) was characterized by pervasive aberrant social behaviors that resulted from "pathogenic care." RAD was included in the category "Disorders Usually First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood or Adolescence," with two subtypes: the emotionally withdrawn/inhibited subtype, in which the child showed little responsiveness to others and no discriminated attachments, and the indiscriminately social/disinhibited subtype, in which the child showed indiscriminate sociability or lack of selectivity in the choice of attachment figures, including attachment to unfamiliar adults and a pattern of social boundary violations. In DSM-5, RAD was recategorized as two distinct disorders within the trauma- and stressor-related disorders: RAD and disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED).

RAD or DSED can occur due to prolonged separation from a parent or caregiver at an early age, as described by Bowlby (1951) and Spitz (1946) and documented on film by Robertson (1952). Both disorders result from the absence of expectable caregiving—that is, they are the result of social neglect or other situations that limit a young child's opportunity to form selective attachments. Other than sharing this type of stressor impacting early development, the two disorders are phenomenologically distinct. Because of dampened positive affect, RAD (formerly known as the emotionally withdrawn/inhibited subtype of RAD) resembles internalizing disorders and converges modestly with depression. In contrast, DSED (formerly known as the indiscriminately social/disinhibited subtype of RAD) more closely resembles attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and converges modestly with it. RAD and DSED have different relationships to attachment behaviors. RAD is essentially equivalent to lack of or incompletely formed preferred attachments to caregiving adults. DSED, in contrast, can occur in children who lack attachments, who have established attachments, or who have secure attachments. The two disorders differ in correlates, course, and response to intervention, and for these reasons are differentiated in DSM-5.

The diagnosis of RAD requires evidence of pervasively disturbed social relatedness before age 5 years. Several sources of information are required, including history, clinical evaluation, and confirmatory observations over time. The history usually includes prolonged separation, severe neglect and/or abuse, or living in institutional settings from an early age. Other observations clarify whether abnormal behaviors observed by a clinician are consistently present and observed by others as well. Observations of the child with the parent or guardian can be made in clinical, family, or other social settings to assess the child's play behavior, acceptance of nurturance, and response to separation and other potential stressors. Videotaping and neuropsychological evaluation may be helpful as well.

DSM-5 describes the essential feature of RAD as absent or grossly underdeveloped attachment between the child and putative caregiving adults (see DSM-5 criteria for reactive attachment disorder in Box 14-1). Children with RAD are believed to have the capacity to form selective attachments, but because of their early development, they fail to show selective attachments. The disorder is associated with the absence of expected comfort-seeking and response to comforting behaviors. These children show diminished or absent expression of positive emotions during routine interactions with caregivers. Their capacity to regulate emotion is compromised, and they display episodes of negative emotions of fear, sadness, or irritability that are not readily explained. This diagnosis should not be made in children who are develop-mentally unable to form selective attachments; therefore, the child must be cognitively at least 9 months old.

|

Box 14-1. DSM-5 Criteria for Reactive Attachment Disorder |

|

313.89 (F94.1) |

Specify if: Persistent Specify current severity: Reactive attachment disorder is specified as severe when a child exhibits all symptoms of the disorder, with each symptom manifesting at relatively high levels. |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

Due to the shared etiological association with social neglect, RAD often cooccurs with developmental delays, especially in cognition and language. Other associated features include stereotypies and other signs of severe neglect (e.g., malnutrition or signs of poor care [Smyke et al. 2002; Zeanah et al. 2005]). RAD is specified as severe when a child exhibits all symptoms of the disorder, with each symptom manifesting at relatively high levels. RAD is considered chronic when it has been present for more than 12 months.

The prevalence of RAD is unknown, but the disorder is seen relatively rarely in clinical settings. Although cases of RAD in young children in the community have not been identified, RAD has been found in young children exposed to severe neglect before either being placed in foster care or being raised in institutions. However, even in populations of severely neglected children, the disorder is uncommon, occurring in less than 10% of such children (Gleason et al. 2011).

Conditions of social neglect are often present in the first months of life, even before RAD is diagnosed. The clinical features of the disorder manifest in a similar fashion for individuals between the ages of 9 months and 5 years (Gleason et al. 2011; Oosterman and Schuengel 2007; Tizard and Rees 1975; Zeanah et al. 2005). Differing cognitive and motor abilities may affect how the symptoms are expressed. Without remediation and recovery through normative caregiving environments, the disorder may persist, at least for several years (Gleason et al. 2011).

Serious social neglect is a diagnostic requirement for the disorder and is the only known risk factor, but the majority of severely neglected children do not develop RAD. The prognosis appears to be dependent on quality of the caregiving environment following serious neglect (Gleason et al. 2011; Smyke et al. 2012). It is unclear whether RAD occurs in older children, and if so, how it differs in presentation. Because of this, the diagnosis should be made with caution in children older than age 5 years.

Attachment behaviors similar to those observed in RAD have been described in young children in many different cultures around the world. However, caution should be exercised in diagnosing RAD in cultures in which attachment has not been studied. RAD significantly impairs young children's ability to relate interpersonally to adults or peers and is associated with functional impairment across many domains of early childhood (Gleason et al. 2011).

The clinician should rule out autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder), and depressive disorders. Conditions associated with neglect, including cognitive delays, language delays, and stereotypies, as well as depressive symptoms, may co-occur with RAD. Medical conditions (e.g., severe malnutrition) also may accompany the disorder.

There are several core elements of treatment of children with RAD. Critical components include facilitating the child's normal development with responsive, consistent parents or other caretakers; encouraging formation of selective attachments; and providing a positively stimulating environment. Forensic involvement and foster placement may be necessary. Other elements include ensuring the child's safety, with adequate housing, as well as providing pediatric care and treatment of medical illnesses; providing an appropriately nurturant caregiver to reverse the pervasive neglect and/or abuse; and, as children grow older, providing psychoeducation about the condition and psychotherapy, including varying types of caregiver or parent-child dyadic therapy directed at the disturbed emotions and relationships (Lieberman 2000).

Despite the pervasiveness and severity of RAD, there have been very few studies of outcome with or without treatment. In accord with initial observations of early emotional deprivation, the symptoms and prognosis appear to depend on the age at which the deprivation begins, its severity, the child's temperament, and the duration of the deprivation situation. In studies of Romanian adoptees, early and long deprivation appeared important in the emergence of attachment disturbances (O'Connor and Rutter 2000; Rutter and O'Connor 2004). Earlier interventions appear to have a greater likelihood of improving outcomes than later interventions. Cognitive and language development, motor development, and self-care are more likely to improve than are problems with social development (O'Connor and Rutter 2000; Rutter and O'Connor 2004; Zeanah 2000).

Although not extensively studied, DSED has been described from age 1 through adolescence. As discussed in the introduction to these disorders of attachment, DSED was one of two subtypes of RAD in DSM-IV, but it is differentiated as a distinct disorder in DSM-5 (see DSM-5 criteria for disinhibited social engagement disorder in Box 14-2).

|

Box 14-2. DSM-5 Criteria for Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder |

|

313.89 (F94.2) |

Specify if: Persistent Specify current severity: Disinhibited social engagement disorder is specified as severe when the child exhibits all symptoms of the disorder, with each symptom manifesting at relatively high levels. |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

Manifestations of DSED differ from early childhood through adolescence. At the youngest ages, across many cultures, children normally are reticent when interacting with strangers and often manifest stranger anxiety (van Ijzendoorn and Sagi-Schwartz 2009). In contrast, young children with DSED fail to show reticence to approach, engage with, and even go off with unfamiliar adults. In preschool children, verbal and social intrusiveness appears prominent and is often accompanied by attention-seeking behavior (Tizard and Rees 1975; Zeanah et al. 2002, 2005). Verbal and physical overfamiliarity continue throughout middle childhood, accompanied by inauthentic expressions of emotion. In adolescence, indiscriminate behavior extends to peers, with more "superficial" peer relationships and conflicts. Adult manifestations of the disorder are unknown.

The prevalence of DSED is unknown, but its occurrence in children in foster care or shared residential facilities appears to be as high as 20% (Gleason et al. 2011).

The principal diagnostic differentiations for DSED are RAD and ADHD. In contrast with RAD, DSED occurs in children who lack attachments, who have established attachments, and who have secure attachments.

Treatments are directed at improving relatedness and interpersonal functioning. There are severe functional outcomes of DSED, which significantly impairs young children's interpersonal relationships with adults and peers (Gleason et al. 2011; Hodges and Tizard 1989).

Box 14-3A presents the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD in adults, adolescents, and children older than age 6 years. Criterion A describes the requisite exposure to the traumatic event. The following criteria consist of two types: 1) those that are specifically related to the traumatic event (Criteria B and C, as well as Criteria D1 and D3) and 2) those that are not (the rest of Criterion D and all of Criterion E). The traumatic event-specific criteria are the more important. When a patient has experienced more than one traumatic event, how can one know that a specific alleged event was causative? The answer lies in the criteria that are specific to the traumatic event. Moreover, most of the criteria that are not specific to the traumatic event are shared by one or more other mental disorders, especially affective and anxiety disorders. In DSM-5, as in previous editions, PTSD is treated solely as categorical (i.e., either PTSD is present or it is not); however, research evidence suggests that posttraumatic psychopathology is dimensional (Forbes et al. 2005).

|

Box 14-3A. DSM-5 Criteria for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

|

309.81 (F43.10) |

|

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Note: The following criteria apply to adults, adolescents, and children older than 6 years. For children 6 years and younger, see corresponding criteria below.

Note: Criterion A4 does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies, or pictures, unless this exposure is work related. Note: In children older than 6 years, repetitive play may occur in which themes or aspects of the traumatic event(s) are expressed. Note: In children, there may be frightening dreams without recognizable content. Note: In children, trauma-specific reenactment may occur in play. . 4. Intense or prolonged psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s). Specify whether: With dissociative symptoms 1. Depersonalization 2. Derealization Specify if: With delayed expression |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

Because the evidence does not support use of adult criteria for PTSD in preschool children, criteria for a new diagnostic subtype (PTSD for children 6 years and younger) have been added in DSM-5 (Box 14-3B). This is an advance from the special developmental considerations in DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000) for specific diagnosis of PTSD in preschool children. Research with traumatized preschool children indicates that they require fewer criteria based on functional impairment from PTSD symptoms and that they have somewhat different responses to stress. The criteria for PTSD in children younger than age 6 years highlight symptom differences in this age group, such as demonstrating trauma reenactment through play and experiencing frightening dreams not clearly related to the traumatic event (Scheeringa et al. 2011).

|

Box 14-3B. DSM-5 Criteria for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

|

309.81 (F43.10) |

|

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder for Children 6 Years and Younger

Note: Witnessing does not include events that are witnessed only in electronic media, television, movies, or pictures. Note: Spontaneous and intrusive memories may not necessarily appear distressing and may be expressed as play reenactment. Note: It may not be possible to ascertain that the frightening content is related to the traumatic event. Persistent Avoidance of Stimuli Negative Alterations in Cognitions Specify whether: With dissociative symptoms 1. Depersonalization 2. Derealization Specify if: With delayed expression |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

PTSD in preschool children requires one intrusion symptom, one avoidance or negative cognition or mood symptom, and two altered arousal and reactivity symptoms or behaviors. These diagnostic requirements reflect increasing data on behavioral signs as well as psychological symptoms in preschool children exposed to severe trauma such as sexual abuse and injuries including burns with significant impairment in function (Scheeringa et al. 2011; Stoddard et al. 2011b). Significantly, most of these children do not meet adult criteria. Continued research is needed to ensure optimal identification and intervention.

The formidable evidence base for the PTSD diagnosis is archived in the medical and psychological literature. A PubMed search of the medical subject heading term "stress disorders, posttraumatic" produced more than 19,000 references. Perhaps the best evidence supporting the reliability and validity of PTSD has come from the rigorously conducted DSM-IV PTSD field trials (Kilpatrick et al. 1998). Supporting the validity of the DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis was the finding that it rarely applied without a major stressor event. There was little variation in PTSD prevalence rates across various proposed Criterion A definitions, indicating that few people developed PTSD unless they had experienced extremely stressful life events. Most people who developed PTSD also experienced substantial subjective emotional and physiological reactions to those events, often characterized as panic reactions. The PTSD criteria changes from DSM-IH-R (American Psychiatric Association 1987) to DSM-IV had only a modest impact on PTSD prevalence rates, suggesting consistency and validity of the diagnostic criteria. Only 11% of cases had symptom onset more than 6 months following the traumatic event. Also, 71% of cases involved a symptom duration of 3 months or more.

Results of the DSM-5 field trials published to date have focused on the reliability of mental disorders as diagnosed in ordinary clinical settings by two independent clinicians using their usual clinical interviews. PTSD was found to be one of the most reliable of all mental disorder diagnoses, with a test-retest reliability kappa value of 0.67 (Narrow et al. 2012; Regier et al. 2013).

Psychophysiological evidence supports the validity of the PTSD diagnosis (Orr et al. 2004), and studies unequivocally demonstrate "marked physiological reactions to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s)" (DSM-5 Criterion B5) in response to trauma-related audiovisual cues and during personal traumatic mental imagery. Abnormalities in regional brain activation in response to traumatic cues and during other tasks have also been shown. Diminished P300 event-related potential (ERP) response to neutral target stimuli in subjects with PTSD supports DSM-5 Criterion E5, problems with concentration. Increased orienting responses and diminished reduction in the P50 ERP found in PTSD subjects support DSM-5 Criterion E3, hypervigilance. DSM-5 Criterion E4, exaggerated startle response, has also been supported in the laboratory. Support for DSM-5 Criterion E6, sleep disturbance, has not been straightforward, but more Stage 1 sleep and less slow-wave sleep, indicative of shallower sleeping, have been demonstrated in patients with PTSD (Kobayashi et al. 2007). DSM-5 Criterion D7, persistent inability to experience positive emotions, is supported by the finding that PTSD subjects show less self-reported expectancy of receiving, and satisfaction with, a monetary reward, accompanied by decreased activation of the brain's reward system (Elman et al. 2009).

There are many cross-sectional studies of PTSD among special populations, including those who have undergone traumatic experiences such as exposure to combat, disasters, rape, or burns, but few large epidemiological studies in the general population. Most representative are those studies in the general population that set an expected baseline rate for the disorder. Studies in the United States are the most common and are cited here. The DSM versions used for diagnosis vary among the studies. The Epidemiological Catchment Area study, an early study using DSM-EH criteria, found low lifetime prevalence rates of PTSD: 1.0% among 2,493 subjects in St. Louis, Missouri, and 1.3% among 2,985 subjects in North Carolina (Davidson et al. 1991; Helzer et al. 1987). A U.S. telephone survey of 4,008 women using the National Women's Study PTSD module found that 12.3% of respondents (17.9% of those exposed to a traumatic event) had a lifetime history of PTSD (Resnick et al. 1993). The National Comorbidity Survey, using DSM-III-R criteria, found lifetime prevalence rates of 5% for males and 10.4% for females (Kessler et al. 1995). The subsequent National Comorbidity Replication Survey, using DSM-TV criteria, found a 12-month prevalence rate of 3.5% (Kessler et al. 2005). PTSD risk factors consistently identified in community studies have been physical assault, rape, female gender, and low socioeconomic and educational levels.

Because of the well-recognized tendency of PTSD patients to avoid painful recollections of psychologically traumatic events, superficial questioning may fail to elicit legitimate symptoms. Conversely, premature direct inquiries into the specific PTSD diagnostic criteria may be treated by some patients, who for whatever reason are motivated to obtain a PTSD diagnosis, as a series of leading questions evoking answers that too readily lead to precisely that.

The interviewer should begin by asking the patient to describe the problems he or she has been experiencing, providing only as much direction as necessary to keep the information flowing and to prevent tangents. The evaluator should carefully consider the report of a patient who talks for 15 or 30 minutes without mentioning a symptom consistent with PTSD, yet answers positively to all PTSD symptoms during subsequent direct questioning. The interviewer should ask the patient who reports nightmares or intrusive recollections to describe several of these in as much detail as possible. Convincing personal details of symptoms support the diagnosis more than do recitations from a textbook.

While eliciting the history, the evaluator should pay close attention to the patient's behavior as part of the mental status examination. Some PTSD symptoms, such as irritability, difficulty concentrating, and an exaggerated startle reflex, may be directly observed. Of special relevance is the degree to which the patient displays consistent emotion while describing the traumatic event and its consequences.

Following the nondirective portion of the interview, the evaluator should conduct a directive interview. Because of potential avoidance on the patient's part, it may not be sufficient for the interviewer merely to ask the patient whether he or she has ever experienced a psychologically traumatic event. Rather, the evaluator may need to ask whether the patient has ever experienced any of various kinds of traumatic events that potentially cause PTSD. Lists and questionnaires, such as the Trauma History Questionnaire (Hooper et al. 2011), are available. A comprehensive evaluation requires that the evaluator, after identifying one or more traumatic events in the patient's history, inquire into each PTSD diagnostic criterion for each event in question, as well as into the criteria for other mental disorders that potentially enter the differential diagnosis. To assist in this task, structured interview instruments for clinician use (originally designed for research use) are available specifically for PTSD (e.g., Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale [Blake et al. 2000], Posttraumatic Symptom Scale—Interview Version [Foa et al. 1993]) as well as for most other mental disorders (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR [First et al. 2002]). Although these instruments currently address DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, updated DSM-5 instruments will soon become available. In addition to instruments offering a categorical determination of the presence or absence of the PTSD diagnosis, several instruments have been developed that provide a continuous measure of PTSD symptom severity in the form of a total score, as well as a subscore for each PTSD symptom cluster, consistent with a dimensional approach to PTSD. Importantly, instruments administered by the clinician (as opposed to a technician) do not require the interviewer to score an item positive just because the interviewee answers affirmatively. Rather, it is the clinician's responsibility to determine through probing whether the detailed historical data satisfy the symptomatic criterion in question.

A number of self-rated psychological questionnaires and psychometric tests for PTSD are available. In contrast to clinician-administered, structured interview instruments, which filter the patient's answers through the clinician's judgment, these paper-and-pencil or computer-administered tests generate a score for each item from the patient's response to that item. As such, these tests are highly vulnerable to either symptom exaggeration or symptom underreporting by patients. Some of these tests incorporate specific scales designed to detect under- or overreporting, which are useful to some extent in forensic settings. Some questionnaires, such as the Detailed Assessment of Posttraumatic Stress (Briere 2001) and the PTSD Checklist (Weathers 2003), have high face validity, in that they inquire directly into the PTSD symptom criteria. Others, such as the Mississippi PTSD Scale (Lauterbach et al. 1997), go beyond the PTSD criteria to inquire into other symptoms and problems thought to be associated with PTSD (although such scales have been criticized as having too general a focus in their assessment of psychopathology). Some personality tests incorporate empirically or theoretically derived PTSD scales (e.g., the Minnesota Multi-phasic Personality Inventory—2 [Butcher et al. 2001] and the Personality Assessment Inventory [Morey 2007]). Perhaps the bottom line for all self-report tests is that they may be useful for screening and for providing ancillary information to confirm or call into question the evaluator's opinion, but they should not be treated as stand-alone tests for the PTSD diagnosis. The current dearth of diagnostically useful biomarkers for PTSD (Pitman and Orr 2003) poses a challenge for future research.

Every practice guideline cites the central place of psychotherapeutic interventions, summarized below, for both prevention and treatment of PTSD (Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense 2010; Institute of Medicine 2012).

Supportive care, including communication and contact with social supports, and medical assistance (Zohar et al. 2009) are recommended as first-line interventions for trauma survivors. Psychological critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), although initially found useful, more recently was shown in group settings either to have no effect or to increase stress and PTSD symptoms, potentially altering the course of or undermining naturally occurring coping mechanisms (Rose et al. 2002; van Emmerik et al. 2002). It is thus not recommended that trauma-exposed individuals who are not seeking help for symptoms be required to debrief their experiences in group or individual session formats, although psychoeducation about typical trauma responses may be helpful.

In contrast to CISD, CBT has been reported to be effective for acute trauma symptoms in trauma survivors in a metaanalysis and a systematic review of the literature (Roberts et al. 2009, 2010). A recent randomized controlled trial of three sessions of a modified prolonged exposure intervention initiated within hours of presentation to an emergency room after a trauma found significantly lower posttraumatic stress reactions 4 and 12 weeks posttrauma, suggesting that individually targeted CBT-based interventions may help prevent the development of PTSD (Rothbaum et al. 2012). It is worth noting, however, that implementing this technique in an emergency setting requires the availability of well-trained and experienced therapists.

At present, the most strongly supported and evidence-based psychotherapies are structured trauma-focused CBT approaches, and these have been recommended as the first-line intervention in PTSD treatment guidelines, with support also for stress inoculation training (Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense 2010; Institute of Medicine 2012). CBT approaches generally target emotion processing of the trauma to enhance extinction, focusing on decreasing avoidance behaviors and reducing negative emotional reactivity. CBT approaches may also include cognitive work focused on distorted beliefs about the self and safety that may arise as a result of the trauma (e.g., see Schmertz et al. 2014). These treatments build on the notion that PTSD is a condition of impeded recovery from an acute reaction to trauma and that much of the psychopathology centers on failure of extinction of fear responses and development of maladaptive cognitions and avoidance behaviors that interfere with recovery. Psychoeducation about PTSD is an important initial component of all CBT approaches, and some approaches also teach stress management techniques such as breathing and relaxation skills (Schmertz et al. 2014).

The CBT approaches with the greatest amount of evidence supporting efficacy include prolonged exposure therapy (PE; Foa et al. 2005) and cognitive processing therapy (CPT; Resick et al. 2008b); both have shown excellent treatment results across a range of populations with PTSD, including PTSD following sexual assault or combat trauma. PE focuses most prominently on 1) repeated imaginal exposure to the primary trauma memories to enhance extinction generally over the course of weekly 90-minute sessions and 2) in vivo exposures to decrease cue reactivity and avoidance. Although not every aspect of a single trauma or every traumatic experience following multiple experiences is necessarily included in exposure work in session, the positive effects on decreased cue reactivity and overall reduction in PTSD symptoms often generalize. In some cases, however, a clinician may select more than one trauma as a target of exposure within a treatment, sequentially starting with the most disturbing one. Variations of PE include virtual reality-enhanced exposure, such as that involving scenes from combat situations in Iraq, which has also demonstrated efficacy (e.g., see Difede et al. 2007); virtual reality may serve to enhance the generalization of extinction outside the therapist's office. PE may be associated early in treatment with heightened anxiety as patients begin to expose themselves to feared and avoided memories. Extinction of reactivity to trauma cues occurs over time, as patients learn that they do not need to fear the memories or their emotional responses to them.

In contrast to PE, CPT utilizes a written account of the traumatic experience but also focuses on reshaping dysfunctional cognitive beliefs that often interfere with recovery; some data suggest that the cognitive component of CPT alone may be effective (Resick et al. 2008a). Typical maladaptive thoughts targeted in CPT include self-blame and guilt, as well as exaggerated beliefs about safety, self-worth, and control. A recent adaptation of CPT designed to be delivered in the context of a couple—with treatment addressing PTSD in the affected individual as well as related interpersonal issues—has been shown to be acceptable and efficacious. Cognitive-behavioral conjoint therapy for PTSD may be helpful for individuals who are resistant to seeking care alone or for whom relationship concerns are central or adaptations of the partner to the PTSD symptoms (e.g., supporting avoidance behaviors) are interfering with recovery (Monson et al. 2012).

Some evidence also suggests that eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) can be beneficial as a PTSD treatment, with efficacy similar to but possibly less consistent than that of PE (Rothbaum et al. 2005; Shapiro 1995). EMDR aims to offer patients additional coping strategies to process and handle traumatic memories, while creating awareness of the safety of their present state. However, some studies have suggested that EMDR's efficacy is driven solely by its exposure component, and it remains unclear whether the eye movement component is required (Davidson and Parker 2001).

Other psychotherapeutic options include group CBT, family therapy, couples therapy, and interpersonal or psychodynamic therapy, however, individual therapy has been demonstrated to be the most effective (Bisson et al. 2007). There has also been growing interest in mindfulness- and acceptance-based approaches (Schmertz et al. 2014). Additional research has focused on ways to improve the retention of extinction learning in CBT with targeted pharmacotherapy prior to exposure sessions, but no such approaches have yet accumulated sufficient evidence to become standard in clinical practice. Finally, when present, comorbid conditions such as alcohol abuse need to be addressed in the context of treatment. Available data supporting the different psychotherapy treatment approaches to PTSD, as well as a number of other treatment approaches, are summarized in the "VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress" (Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense 2010) and in the Cochrane and Institute of Medicine reports (Bisson and Andrew 2007; Institute of Medicine 2012).

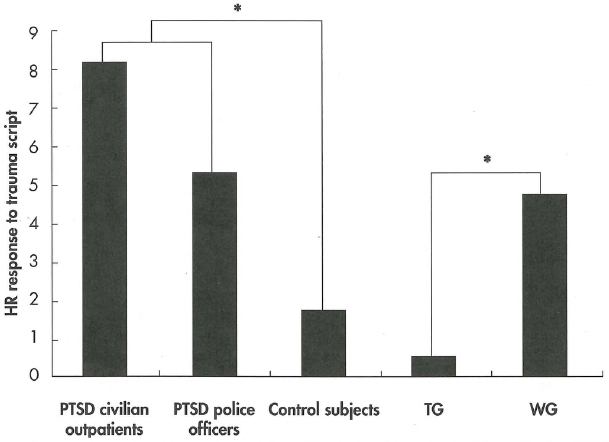

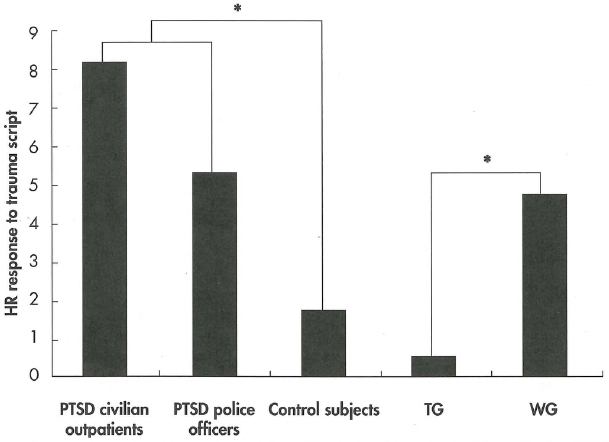

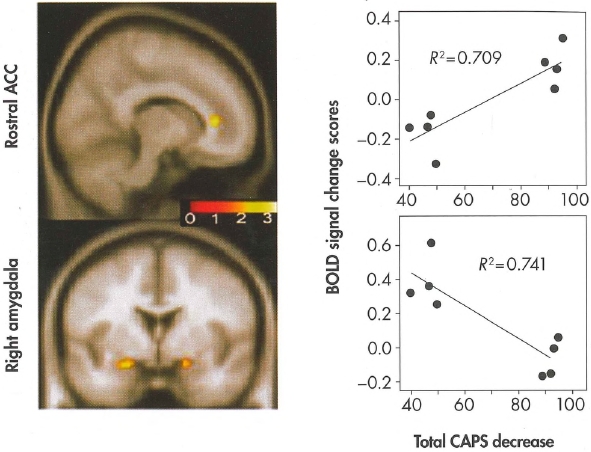

Preliminary evidence suggests that psychotherapy is capable of at least partially reversing biological abnormalities in PTSD, including increased physiological responses during traumatic mental imagery (Lindauer et al. 2006; Figure 14-1) and reduced inhibition of the amygdala by the vmPFC (Felmingham et al. 2007; Figure 14-2).

Psychopharmacotherapies for PTSD are integral to the treatment of patients with severe symptoms and significant impairment in most settings. More research is needed to guide clinicians as to which patients are more likely to respond to medication or to psychotherapy and which may achieve optimal benefit from starting with a combination of these strategies or combining them sequentially only when needed. Furthermore, additional research is needed to better understand whether there may be differences in response to pharmacotherapy for combat-related PTSD compared with other types. With pharmacotherapy, it is important to monitor for both treatment-emergent and long-term side effects and toxicity, as well as to elicit patients' beliefs about medication, all of which may impact compliance with treatment and long-term treatment efficacy.

Figure 14-1. Heart rate responses to trauma scripts in two posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) populations and a control group, and the effects of psychotherapy in a randomized controlled trial.

HR=heart rate; TG=treatment group posttreatment; WG=waitlist group posttreatment.

*P<0.05.

Source. Courtesy of Dr. Ramon Lindauer, from Lindauer RT, van Meijel EP, Jalink M, et al: "Heart Rate Responsivity to Script-Driven Imagery in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Specificity of Response and Effects of Psychotherapy." Psychosomatic Medicine 68:33-40, 2006. Copyright 2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Used with permission.

Figure 14-2. Correlation between changes in blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) activity and changes in total severity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—i.e., changes in total score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)—following exposure-based treatment.

To view this figure in color, see Plate 7 in Color Gallery in middle of hook.

The functional maps display the areas where changes in BOLD activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and amygdala correlated with changes in total CAPS score; the color scale represents the strength of the correlation. The scatter plots display the direction of these correlations (improvement on total CAPS on the horizontal axis; extent of BOLD activity on the vertical axis).

Source. Courtesy of Dr. Kim Felmingham. Image prepared by Dr. Felmingham and used with her permission.

The evidence base for pharmacotherapeutic treatment of adults is large and includes research on a wide range of drugs, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants, among others. SSRIs are the standard of care in many treatment guidelines because of their efficacy and safety, as demonstrated in many positive trials, often with pharmaceutical company funding (Brady et al. 2000, 2005; Connor et al. 1999; Davidson and Parker 2001; Marshall et al. 2001; Martenyi et al. 2002, 2007; Tucker et al. 2001). The endorsement of SSRIs is not universal, however. Signs of controversy include the conclusion by the Institute of Medicine (2008) that the evidence for efficacy of SSRIs and other medications is not sufficient, as well as the conclusion, with which most do not agree, by the U.K.'s National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2005), that mirtazapine is an agent of choice.

Currently, use of an SSRI, such as sertraline, fluoxetine, or paroxetine, or the SNRI venlafaxine is recommended as a first-line treatment by most organizations, including the British Association of Psychopharmacology (Baldwin et al. 2005), American Psychiatric Association (2004, 2009), Canadian Psychiatric Association (2006), World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (Bandelow et al. 2008), and International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (Foa et al. 2009), as well as the guidelines of the International Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project (Davidson et al. 2005), the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (2010), and the Institute of Medicine (2012). SSRIs are the only medications shown to be effective in reducing the full range of PTSD symptoms (Brady et al. 2000; Davidson et al. 1996; van der Kolk et al. 1994). The evidence for SSRIs has been reported in Cochrane Reviews as being strong for both short-term and maintenance treatments in chronic PTSD (Stein et al. 2006) and for reducing symptom severity (Ipser and Stein 2012).

It should be noted, however, that 1) antidepressants now have a class warning for potential increased risk of suicidality in individuals ages 24 years and younger, and 2) citalopram in particular has been reported to be associated with QTc prolongation; therefore, recommended doses are now limited by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to 40 mg/day for adults who have no other risk factors and 20 mg/day for adults who are older than 60 years, adults who have hepatic impairment, or adults who are poor metabolizers of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 or who are taking CYP2C19-inhibiting medications. A recent large study using Veterans Health Administration data, however, found no evidence of elevated ventricular arrhythmia or all-cause cardiac or noncardiac mortality associated with citalopram dosages greater than 40 mg/day (and lower risks for 21-40 mg/day than for 1-20 mg/day), and questioned the merit of the dose warning (Zivin et al. 2013). Although optimal dosing of antidepressants in treating PTSD remains unclear, many patients do benefit from gradual dosage escalation to optimize response.

Although many clinicians employ benzodiazepines for acute stress disorder and PTSD, with increased use from 2003 to 2010 (Hawkins 2012), some, including the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (2010), caution against using them for PTSD due to theoretical risks of interference with extinction learning, based on animal and very limited human research. Benzodiazepines might increase PTSD development with early use or interfere with extinction-based psychotherapies.

There is a lack of evidence for benzodiazepine efficacy as monotherapy, as well as a risk of abuse in a population already at elevated risk for alcohol and substance use disorders. However, sleep disturbances, including nightmares, are among the most common and highly distressing PTSD symptoms often targeted with pharmacotherapy, and efforts are being made to find alternatives to benzodiazepines. Prazosin, an α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, has been investigated in the treatment of posttraumatic nightmares, and a systematic review found that three of four randomized controlled trials and several other studies demonstrated its benefit for this indication (Kung et al. 2012). Limited data are emerging for other sleep agents, such as eszopiclone (Pollack et al. 2011), but more research on the short- and long-term efficacy and risks with this class of medications is needed.

A range of anticonvulsants have been studied for PTSD but have not shown strong evidence of efficacy, and none are first line. It is worth noting as well the FDA class warning from 2009 for elevated risk of suicidal ideation and behavior associated with anticonvulsants (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009).

Finally, antipsychotic agents such as olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone have been studied as monotherapy and/or augmentation therapy for PTSD (with mixed results) as well as for specific symptoms such as sleep disturbance. The most recent large randomized controlled study of risperidone in chronic military-related PTSD failed to show efficacy (Krystal et al. 2011). Although these newer antipsychotics may differ within class regarding efficacy and tolerability and do not carry the risk of abuse of benzodiazepines, they also are associated with short- and long-term side effects that must be carefully monitored longitudinally. It is worth noting that in a naturalistic study of 237 veterans with PTSD, prazosin had efficacy similar to that of quetiapine but was better tolerated and more likely to be continued (Byers et al. 2010). Other novel agents and approaches, such as employing D-cycloserine prior to exposure as a strategy to enhance extinction learning in psychotherapy (de Kleine et al. 2012), have begun to be studied based on translational research findings. Such approaches offer hope for a new direction for combined treatment, but to date they lack significant support in initial PTSD-specific research.

For the treatment of children and adolescents with PTSD, the "Practice Parameter of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry" (AACAP; Cohen et al. 2010) endorses consideration of SS-RIs but indicates that these agents have some risks. The AACAP cautions that due to possible hyperarousal with irritability, poor sleep, or inattention, SSRIs may not be an optimal treatment when used alone in the absence of psychotherapy. Therefore, the AACAP advises beginning with trauma-focused CBT and adding an SSRI if severity of symptoms indicates a need for more interventions (Cohen et al. 2007). A large double-blind study of sertraline compared with placebo found no benefit of sertraline in children (Robb et al. 2010), and a small double-blind study of sertraline to prevent PTSD in burned children indicated a marginal benefit based on parent but not child report (Stoddard et al. 2011c).

In addition to SSRIs, alternative medications for consideration, based on open trials, include α- and β-adrenergic blocking agents, antipsychotic agents, imipramine, and anticonvulsants. Despite wide clinical use, no evidence-based study has established the benefit of benzodiazepines, propranolol, or clonidine for PTSD in children, and no evidence-based study supports antipsychotics for child PTSD. A small open study of risperidone showed remission of severe PTSD symptoms (Horrigan and Barnhill 1999); however, weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and other adverse effects are of growing concern with atypical antipsychotics in children (Almandil et al. 2013; Bobo et al. 2013; Cohen et al. 2012). Although clonidine may have benefit in reducing arousal and anxiety, it carries significant cardiovascular risk.

Despite interest, little research has been done on complementary and alternative medicine therapies, and research to date has had flawed methodologies. Findings from a comprehensive review suggest that meditation techniques may produce moderate improvements in PTSD severity and quality of life, and that acupuncture may be comparable to group CBT (Strauss et al. 2011).

Longitudinal studies of PTSD have found that complete recovery occurs in up to 50% of cases within 3 months, while many individuals have symptoms lasting for more than 1 year (Blanco 2011). The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma indicated that the median time for PTSD to remit was 24.9 months (Breslau et al. 1998). A study of the U.S. general population showed that PTSD persisted over 60 months in over one-third of individuals (Kessler et al. 1995).

Acute stress disorder (ASD) was added in DSM-IV to identify clinically significant posttraumatic symptomatology that developed within 1 month of a traumatic event. The diagnosis was introduced in 1994 because of the observation that certain symptoms appeared to predict the development of PTSD.

In DSM-IV-TR, ASD criteria were similar to those for PTSD; the diagnosis required the presence of at least three of five dissociative symptoms, one of six reexperiencing symptoms, marked avoidance, and marked anxiety or increased arousal. In DSM-5 (see Box 14-4), the ASD diagnosis requires the presence of at least 9 of 14 symptoms in any of five categories—intrusion symptoms, negative mood, dissociative symptoms, avoidance symptoms, and arousal symptoms—beginning or worsening after the traumatic events and persisting for 3 days (instead of the 2 days required in DSM-IV) to 1 month after the trauma. (The threshold of 9 of 14 symptoms is based on analysis of data from Israel, the United Kingdom, and Australia [Bryant et al. 2011].) The diagnosis of ASD in DSM-5 still includes—but no longer requires—dissociative symptoms (Bryant et al. 2011).

|

Box 14-4. DSM-5 Criteria for Acute Stress Disorder |

|

308.3 (F43.0) |

Note: This does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies, or pictures, unless this exposure is work related. Intrusion Symptoms Negative Mood Dissociative Symptoms Avoidance Symptoms Arousal Symptoms Note: Symptoms typically begin immediately after the trauma, but persistence for at least 3 days and up to a month is needed to meet disorder criteria. |

To differentiate normal, adaptive reactions to acute stress within 48 hours of exposure to combat or disasters from acute stress disorder, the term "acute stress reaction" or "combat stress reaction" was used to describe symptoms of stress within that early period (Friedman et al. 2011). The rationale for diagnosis ASD beginning 2 days and for up to 1 month after a traumatic event was justified first by common clinical manifestation of significant acute stress symptomatology that resolves within 1 month, and second by the acute presence of dissociation, which has been associated with the development and chronicity of PTSD (Bryant et al. 2011). Dissociation has not, however, been demonstrated to be a necessary independent predictor of PTSD diagnosis, and the majority of people with PTSD did not meet criteria for ASD requiring dissociation (Bryant et al. 2011).

The prevalence of ASD after a severe traumatic event is highly variable across studies and types of traumatic exposures and populations (Bryant et al. 2011).

Clinical assessment of the acutely traumatized patient often requires behavioral observation, careful history taking, and listening to the patient's narrative story for symptomatology consistent with ASD. Therapeutic aspects of an assessment by an interested, listening clinician may contribute to the patient's feeling understood and better explaining the symptoms he or she is experiencing. After an acute traumatic event, patients may be unable for psychological or medical reasons to report their symptoms, and repeated evaluations are often necessary.

There are several instruments helpful in screening for ASD in children or adults, as well as more time-consuming full diagnostic measures. (Current instruments address DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, but updated DSM-5 instruments will soon be available.) One instrument used to screen for ASD in children is the Child Stress Reaction Checklist (Saxe et al. 2003), and two scales used to assess intrusive symptoms in adults are the Impact of Events Scale—Revised and the Acute Stress Disorder Scale (Bryant et al. 2000).

Differential diagnosis should include potentially treatable contributors to post-traumatic symptoms, such as preexisting illness (including PTSD), infection, metabolic disturbance, side effects of pharmacotherapies (e.g., morphine), neurological injury after head trauma, and psychoactive substance (e.g., alcohol) use disorders or withdrawal.

According to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria (Box 14-5), an adjustment disorder requires the development of clinically significant emotional or behavioral symptoms in response to an identifiable stressor. The symptoms must occur within 3 months of the onset of the stressor (Criterion A) and must resolve within 6 months after the stressor is removed (Criterion E). Adjustment disorders can be classified as one of six sub-types: 1) with depressed mood, 2) with anxiety, 3) with mixed anxiety and depressed mood, 4) with disturbance of conduct, 5) with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct, or 6) unspecified.

|

Box 14-5. DSM-5 Criteria for Adjustment Disorders |

Specify whether: With depressed mood With anxiety With mixed anxiety and depressed mood With disturbance of conduct With mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct Unspecified |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

For DSM-5, three major changes from the DSM-IV-TR adjustment disorder diagnosis were considered: 1) addition of an ASD/PTSD subtype, 2) addition of a bereavement-related subtype, and 3) removal of the bereavement exclusion (Criterion D). These changes would have required adjustments to symptom duration requirements to differentiate the ASD and PTSD subtypes and to accommodate the extended (>12 months) symptom persistence of the bereavement-related sub-type, which was meant to identify a syndrome of prolonged or complicated grief, a new condition that has a growing evidence base (Shear et al. 2011) but has not previously been included in DSM. The ASD/PTSD and bereavement-related subtypes were ultimately not added to the diagnostic criteria (Strain and Friedman 2011); instead, persistent complex bereavement disorder was placed under "Conditions for Further Study" in DSM-5 Section III and was also referenced as a subtype of other specified trauma- and stressor-related disorder (see section "Other Specified or Unspecified Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorder" later in this chapter). Criterion D was also clarified as an exclusion only when symptoms are explained by normal bereavement, based on what normally would be expected when cultural, religious, or age-appropriate norms for intensity, quality and persistence of grief reactions are taken into account. Depending on symptom duration, subsyndromal but chronic PTSD-like presentations could also potentially be assigned a diagnosis of adjustment disorder, unspecified type, or could be recorded under the other specified trauma-and stressor-related disorder category of "adjustment-like disorders with prolonged duration of more than 6 months without prolonged duration of stressor" (see Box 14-6 later in this chapter).

There has been debate over the diagnosis of adjustment disorders since their inclusion in DSM-III-R (Carta et al. 2009; Casey and Bailey 2011). Controversies have included the absence of a specific symptom profile, the differentiation of adjustment disorders from a normal response to stressors, symptom overlap with other psychiatric disorders, difficulty standardizing assessments or interventions when the condition is not clearly defined, and the lack of stability of the diagnosis over time. These issues have contributed to the current lack of an informative, empirical evidence base supporting this diagnosis.

Because an adjustment disorder, like PTSD and ASD, requires the presence of a stressful event that results in clinically significant symptoms, distress, or impairment, adjustment disorders are now classified in DSM-5 together with other trauma- and stressor-related conditions to clarify that these disorders are associated with negative outcomes such as suicide and may require acute intervention (Strain and Friedman 2011). The evidence base, however, is quite limited, and the range of possible stressors and symptom profiles is broad. Also, many people diagnosed with adjustment disorders have symptom profiles that overlap with but are subsyndromal for DSM mood and anxiety disorder diagnoses. The stressor itself can also range dramatically. Whereas bereavement-related depression could have been coded as an adjustment disorder in DSM-IV, the bereavement exclusion was dropped from major depressive disorder in DSM-5, in part because of data showing that major depressive disorder does not differ significantly on the basis of whether it is triggered by a loss or by other life stressors; such data examining potential differences in symptoms and associated impairment based on type of stressor are not yet available for adjustment disorders. The addition of a PTSD/ASD sub-type and a bereavement-related subtype to the diagnostic criteria was considered for DSM-5, but these subtypes were ultimately not included under adjustment disorder (Strain and Friedman 2011).

Although robust epidemiological studies are lacking, it is estimated that 9%-36% of patients seen in public-sector psychiatry settings are given an adjustment disorder diagnosis (Koran et al. 2002; Shear et al. 2000). Similarly, in emergency settings, almost one-third of those evaluated for self-harm are diagnosed with an adjustment disorder, whereas in consultation-liaison psychiatry settings, approximately 12% of referrals are diagnosed with an adjustment disorder (Strain et al. 1998), although the incidence may be even higher. Finally, although large epidemiological studies are needed, the overall population prevalence rate of adjustment disorders has been estimated at 1% (Ayuso-Mateos et al. 2001).

Because of the lack of specific symptom requirements for adjustment disorders, clinical judgment is required. Adjustment disorders provide a useful category to allow clinicians to treat clinically distressed individuals who do not meet other diagnostic criteria (Strain and Friedman 2011). Although depression scales are sometimes used, this limited specification has made standardized symptom severity assessments somewhat difficult to develop. Adjustment disorders are included in structured clinical interviews such as the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al. 1998) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (First et al. 2002). More recently, a self-report assessment of adjustment disorders has been developed that includes three factors: intrusion, avoidance, and failure to adapt (Einsle et al. 2010). This measure was found to be reliable and valid and has potential for use as a screening instrument.

Given that adjustment disorders have been associated with elevated risk for suicide, any patient with an adjustment disorder diagnosis should receive a careful safety assessment and treatment plan. Empirical support for the treatment of adjustment disorders is limited, however. Whereas some authors have argued that psychological interventions should be preferred over pharmacotherapy (Carta et al. 2009; Casey and Bailey 2011), others have advocated for antidepressant use (Stewart et al. 1992), especially if no improvement is seen from psychotherapy. Because some subsyndromal subtypes of conditions such as major depressive disorder and PTSD would meet DSM-5 criteria for adjustment disorders, subsyndromal treatment research as well as evidence supporting effective targeting of symptom clusters in adjustment disorder subtypes may provide guidance to clinicians treating adjustment disorders.

With the exclusion of ongoing supportive therapy for persistent stressors, brief therapies are considered the most appropriate psychological interventions for adjustment disorders (Casey and Bailey 2011), despite the scarcity of controlled data. Some controlled data on individuals with work-related stress suggest that cognitive therapy may be effective (van der Klink et al. 2003). However, clinicians have worked successfully with a range of individual or group approaches, including psychodynamic, cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal, couples and family, and mindfulness-based interventions; exercise; and problem-solving approaches (Casey and Bailey 2011). It may be that some treatments best target specific types of stressors; for example, a randomized controlled trial by Shear et al. (2005) supported the efficacy of complicated grief therapy, a targeted psychotherapy, for individuals with complicated grief (see discussion of persistent complex bereavement disorder in section "Other Specified or Unspecified Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorder"). Additional research is needed to study optimal psychological interventions for each adjustment disorder sub-type.