CHAPTER 12

Anxiety Disorders1

Fear is a response to external threat. Fear or fearlike behaviors are seen in most mammals and are often used as animal models for anxiety. Anxiety, a common human emotion, is an affect; it is an internal state, focused, very much on anticipation of danger. It resembles fear but occurs in the absence of an identifiable external threat, or it occurs in response to an internal threatening stimulus. Anxiety that is disabling or that results in extreme distress is only "normal" when it occurs under tremendous stress and is short-lived. In such instances, a diagnosis of an adjustment disorder (with anxiety) may be appropriate. When anxiety occurs in the absence of substantial stress, or when it fails to dissipate when the stressor abates, an anxiety disorder is likely.

Anxiety disorders are commonly encountered in clinical practice. In most studies of primary care settings (e.g., Lowe et al. 2008), anxiety disorders (10%-15% of patients) are more common than depressive disorders (7%-10% of patients). In a general psychiatric outpatient practice, anxiety disorders will comprise up to 40% of new referrals.

Much of the treatment of anxiety disorders can be successfully carried out by the primary care treatment provider (e.g., family doctor or internist). The psychiatrist usually plays a consultative role or manages the patients who are most difficult to treat.

In this chapter we briefly review the epidemiology of anxiety disorders, risk factors for these disorders, and comorbidity. This review is followed by a detailed discussion of specific anxiety disorders and their treatment.

Among the mental disorders, anxiety disorders are the most prevalent conditions in any age category. They are associated with substantial cost to society due to disability and loss of work productivity. Emerging evidence shows that anxiety disorders are associated with increased risk of suicidal behavior (Sareen 2011). Table 12-1 summarizes the prevalence rates, median ages at onset, and gender ratios of anxiety disorders in the U.S. general population (Kessler et al. 2012). Among the anxiety disorders, the phobias—particularly specific phobia and social anxiety disorder (SAD)—are the most common conditions, with lifetime prevalence rates greater than 10%. Panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), agoraphobia, and separation anxiety disorder (SepAD) each have lifetime prevalence rates between 2% and 7%. SAD and specific phobia have a lower median age at onset than the other anxiety disorders. It is important to emphasize that the majority of epidemiological studies on mental disorders are from the United States, and cross-national studies have shown that there are differences in the prevalence rates of these and other mental disorders across nations (Kessler and Ustün 2004).

Studies have shown that there is a constellation of risk factors that, for the most part, are common to all of the anxiety disorders (Kessler et al. 2010). Female sex, younger age, single or divorced marital status, low socioeconomic status, poor social supports, and low education are associated with an increased likelihood of anxiety disorders. Whites are more likely to have anxiety disorders than ethnic minorities. Stressful life events and childhood maltreatment are also strong risk factors for anxiety disorders. Among genetic and family factors, there is increasing evidence for the familial transmission of anxiety disorders through both genetic transmission and modeling.

Anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with other mental disorders, personality disorders, and physical health conditions, with over 90% of persons with an anxiety disorder having lifetime comorbidity with one or more of these disorders (El-Gabalawy et al. 2013). Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with other conditions often leads to poorer outcomes and affects treatment. The most common comorbidity is the presence of another anxiety disorder. Mood and substance use (including nicotine and alcohol) disorders also commonly co-occur with anxiety disorders. Because anxiety disorders often precede the onset of mood disorders and substance use, early interventions to treat anxiety disorders may prevent mood and substance use disorders. Anxiety disorders are also commonly comorbid with personality disorders, such as borderline, antisocial, and avoidant personality disorders (El-Gabalawy et al. 2013).

Physical health conditions are also common among patients with anxiety disorders (Sareen et al. 2006). Among the comorbid physical health conditions, the most prevalent are cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness (e.g., asthma), arthritis, and migraines. The onset of a serious physical illness might trigger the onset of an anxiety disorder, or conversely, anxiety and avoidance might lead to physical health problems.

|

Table 12-1. Approximate lifetime and 12-month prevalence, gender ratio, and median age at onset for anxiety disorders in the U.S. general population |

||||

| Disorder | Lifetime prevalence (%) | 12-month prevalence (%) | Gender ratio (F:M) | Median age at onset (years) |

|

Panic disordera |

3.8 |

2.4 |

1.8:1 |

23 |

|

Agoraphobiab |

2.5 |

1.7 |

1.8:1 |

18 |

|

Social anxiety disorder/social phobia |

10.7 |

7.4 |

1.4:1 |

15 |

|

Generalized anxiety disorder |

4.3 |

2.0 |

1.8:1 |

30 |

|

Specific phobia |

15.6 |

12.1 |

1.5:1 |

15 |

|

Separation anxiety disorder |

6.7 |

1.2 |

1.6:1 |

16 |

aRegardless of presence or absence of agoraphobia.

bRegardless of presence or absence of panic disorder.

Source. Adapted from Kessler et al. 2012.

Case Example

A 21-year-old single woman comes to the visit with her psychiatrist accompanied by her mother. The young woman has never had a driver's license, and she states that her mother drives her everywhere. She has come in because of recurrent physical complaints (including abdominal pain and headaches) that have baffled her primary care physician and so far defied diagnosis. Diagnostic interview reveals a long-standing history of dependence on the parents, which has worsened since the father's death by cancer several years prior. Childhood history is noteworthy for a lifelong history of fear and discomfort when separated from her parents. She never attended day camp or sleep-away camp as a child, and the parents never traveled without their daughter. Elementary school was marked by numerous absences due to a combination of physical complaints and outright school refusal.

Since DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association 1980), separation anxiety disorder has been included as a diagnosis in the section "Disorders Usually First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence." In DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013), the decision was made to move some disorders with typical childhood onset into the respective adult sections, hence the move of Sep AD into the "Anxiety Disorders" section. Interestingly, it was possible to diagnose Sep AD in adults even prior to DSM-5—there was nothing in the criteria to prohibit it—but its placement in the "Disorders Usually First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence" section may have left the impression that Sep AD was a "childhood only" disorder. It has been hypothesized by some that the move of Sep AD into the "Anxiety Disorders" section in DSM-5 will result in an increased application of the diagnosis in adults. The new diagnostic criteria implicitly permit the diagnosis of Sep AD to be made even if onset is in adulthood; this is a controversial element of the criteria that will require further research.

SepAD would be diagnosed when there is evidence of developmentally inappropriate and excessive anxiety occurring upon separation (or threat of separation) from significant attachment figures (see DSM-5 criteria for separation anxiety disorder in Box 12-1). In children, this is best exemplified by excessive crying, tantrums, physical complaints, and other manifestations of fear and avoidance of separation. Young children may have difficulty expressing the reason for their discomfort, but older children can usually explain their fearfulness that something bad will happen to the individual(s)—typically the parent(s)—if they are separated. In adults, the concerns about separation from significant others and the worry about harm befalling them are usually much more readily expressed, though the pattern of behavior can be so long-standing and ingrained—extending longitudinally since childhood—that both the patient and the significant other may rationalize the behaviors. The presentation in adulthood is one of extreme dependence, and in fact, a diagnosis of dependent personality disorder may well apply; in such instances, both diagnoses can be made. SepAD is the appropriate diagnosis in many cases of "school phobia"; the other common explanatory diagnosis is SAD.

|

Box 12-1. DSM-5 Criteria for Separation Anxiety Disorder |

|

309.21 (F93.0) |

|

The course of Sep AD has not been well studied, but periods of exacerbation and remission are often noted. Onset may be as early as preschool age and may occur at any time during childhood, though more rarely in adolescence. Persistence into adulthood can occur (Manicavasagar et al. 2010), although most cases of childhood Sep AD resolve prior to adulthood.

Because the diagnosis of Sep AD has not been widely considered prior to DSM-5 in the differential diagnosis of anxiety in adults, it is difficult to determine what kinds of diagnostic dilemmas might present. Agoraphobia is a likely source of diagnostic confusion, since both Sep AD and agoraphobia may present with pervasive situational anxiety and avoidance, and both may be associated with excessive dependence and concerns about inability to function in certain situations if left alone. What should differentiate them is the content of the cognitions, with Sep AD patients emphasizing the separation worries. Panic disorder will also enter the differential diagnosis and, in fact, patients with Sep AD may have panic attacks when faced with an unwanted separation from a significant attachment figure. What should distinguish panic disorder is the unexpected nature of the panic attacks. Symptomatic overlap with GAD, wherein sufferers have multiple worries that often involve the health and welfare of significant others, is expected to be substantial; but in Sep AD, the worries should be limited to separation from significant others and the feared consequences thereof.

Very little is known about the etiology of Sep AD. It is believed to share a genetic basis, through traits such as neuroticism, with many of the other anxiety disorders. Genetic links with panic disorder are believed to be especially strong (Roberson-Nay et al. 2012).

Case Example

A 6-year-old boy is brought to the mental health clinic by his mother. He has been referred by his pediatrician for failure to speak in situations outside of the home. Extensive speech and hearing assessment and psychoeducational testing prior to referral have failed to indicate any evidence of a communication or other developmental disorder. The boy performs above grade level on tests of comprehension and, according to parental report, language expression. But he had entered first grade 3 months prior to the referral and had not spoken to any teacher or teacher's aide or, as far as anyone could tell, any of the other children in the class. On evaluation by the psychiatrist, the boy smiles appropriately when greeted but looks downward or at his mother during most of the assessment. He occasionally nods or shakes his head in response to questions that require yes/no answers, but sometimes does not respond at all. When pressed (gently) to respond verbally, he eventually whimpers and begins to cry, at which point the interview is terminated by the examiner. The mother indicates that her son speaks well—and frequently—when at home but that no one has ever witnessed him speaking to anyone other than her or his father. The boy does have play dates with other children his age, and he plays board games, participates in some sports (swimming), and enjoys watching TV. He recently started passing short written notes to teachers and other children in his class, in lieu of speaking.

Selective mutism was present in DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) and its precursors (where it had been referred to as "elective mutism") but resided in the "Disorders Usually First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence" section. In DSM-5 the decision was made to move some disorders with typical childhood onset into the respective adult sections, and after some deliberation about where to put selective mutism, it was decided that it belonged in the Anxiety Disorders section, even though it had not previously been classified as an Anxiety Disorder.

Selective mutism is characterized by the failure of the individual (almost invariably a child) to speak in nearly all social situations, despite apparently normal language development and abilities, as evidenced by speech with familiar people (typically the parents). (DSM-5 criteria for selective mutism are presented in Box 12-2.) Onset is in early childhood; however, precise age-at-onset data are not available, nor are good epidemiological data on the prevalence of selective mutism (although it is considered to be relatively uncommon, affecting approximately 1 in 1,000 children according to some estimates) (Bergman et al. 2002).

|

Box 12-2. DSM-5 Criteria for Selective Mutism |

|

312.23 (F94.0) |

|

For children with selective mutism, failure to speak is not limited to the presence of adults or other unfamiliar people; these children do not speak even among their peers. The failure to speak is also consistent, in that it occurs reliably across social situations and across time (see DSM-5 criteria for selective mutism [Box 12-2]). DSM-5 specifically reminds clinicians not to diagnose selective mutism until the first month of the school year has passed, to ensure that the mutism is not merely a transient phenomenon related to initial discomfort with starting school. Selective mutism is frequently diagnosed either in kindergarten or in first grade—where parents may be surprised by reports from the teacher that their child, who speaks well and often at home, has not said a word to anyone. The mutism must also be seen (usually in the eyes of the parents and/or teachers) to interfere with either the academic or social aspects of school or other activities.

Although selective mutism may be more common among immigrant families owing to difficulties with the new culture and language (Elizur and Perednik 2003), DSM-5 specifically states that the disorder should not be diagnosed if failure to speak is due to a lack of knowledge of, or comfort with, the spoken language required in the social situation. Application of this criterion in clinical practice can require a nuanced interpretation of the criteria: Compared to other immigrants from that culture, is the failure to speak clearly aberrant? If so, a diagnosis of selective mutism could be applied. A similar rule of thumb may be applied to selective mutism in bilingual families.

Children with selective mutism may not be entirely mute in situations where they would be expected to speak. Sometimes a child with selective mutism may have one peer with whom speech is engaged—though often as a whisper or other shorthand form of verbal communication. The passing of notes (or, increasingly, electronic texts) is common among slightly older children who are able to write/text.

An area of difficulty in differential diagnosis pertains to the criterion that the mutism not be better accounted for by a communication disorder or a neurodevelopmental disorder. Whereas extreme stuttering, for example, would contraindicate the application of a selective mutism diagnosis, studies show that children with selective mutism are, as a group, more likely than children without selective mutism to have various subtle receptive and expressive language problems (Cohan et al. 2008; Manassis et al. 2007; Mclnnes et al. 2004). In such instances, the diagnosis of selective mutism may be applied, but attention to potentially remediable communication or other neuro-developmental disorders should not be neglected in treatment planning.

Most children with selective mutism are socially anxious and, in fact, meet diagnostic criteria for SAD. This has led most clinical investigators to consider selective mutism as an early-onset, severe subtype of SAD (Bögels et al. 2010; Carbone et al. 2010; Cohan et al. 2006), and in fact, at one point in the development of DSM-5, there was discussion about classifying selective mutism as such (i.e., a sub-type of SAD). But it was ultimately decided to classify selective mutism as an anxiety disorder separate from SAD, and await additional research before concluding that selective mutism is a subtype of SAD. Accordingly, it is expected that the vast majority of children with selective mutism will also be diagnosable with SAD and that both disorders will be coded.

Little is known about the etiology of selective mutism. As noted above, the vast majority of children with selective mutism are also diagnosable with SAD, and it is also the case that they have very strong family (parental) histories of SAD (Chavira et al. 2007). A single yet-to-be-replicated study found an association between selective mutism and variation in a gene, CNTNAP2 (Stein et al. 2011b); however, the implications of this finding are as yet unknown.

Case Example

A 25-year-old white woman presents with a fear of needles. She describes repeated avoidance of medically recommended blood tests because of the fear of fainting. She understands that her fear is "irrational," but she is unable to overcome it. She has avoided getting blood tests recommended by her doctor, and she has had dental procedures without anesthetics due to her fear of needles. She describes a 10-year history of this fear. At the age of 15, she received an immunization in school and fainted as soon as she got up after getting the needle. She would like to start a family, and her doctor has recommended that she get some psychological help for her fears.

A key feature of specific phobia is that the fear or anxiety is limited to the phobic stimulus, which is a specific situation or object. DSM-5 has codes for specifying the various types of situations or objects that may be involved: animal, natural environment, blood-injection-injury, situational, and other (see DSM-5 criteria for specific phobia in Box 12-3).

|

Box 12-3. DSM-5 Criteria for Specific Phobia |

Note: In children, the fear or anxiety may be expressed by crying, tantrums, freezing, or clinging. Specify if: Code based on the phobic stimulus: 300.29 (F40.218) Animal 300.29 (F40.228) Natural environment 300.29 (F40.23x) Blood-injection-injury 300.29 (F40.248) Situational 300.29 (F40.298) Other |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

In order to differentiate specific phobias from normal fears that are so common in the general population, specific phobias must be persistent (though this characteristic, of course, depends on the opportunity for exposure to the situation or object), the fear or anxiety must be intense or severe (sometimes taking the form of a panic attack), and the individual must either be routinely taking steps to actively avoid the situation or object or be intensely distressed in its presence. As is the case for all phobias, the fear and/or avoidance in specific phobias must be disproportionate to the actual danger posed by the situation (Craske et al. 2009). This criterion may not be all that easy to judge. Most people recoil when they see a snake. Does that mean that nearly everyone has a snake phobia? Certainly not. People with snake phobias are so frightened by the prospect of encountering a snake that they may refuse to ever go hiking, to go for walks in the park, and even to look at pictures of snakes. If such an individual actually moved to a region with no snakes so that they could be avoided completely, does this individual no longer have a snake phobia? This is a gray area in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, but, practically speaking, it is only an issue for epidemiologists seeking to determine the prevalence of specific phobias. For clinicians, if they encounter a patient seeking help because of his or her fear of snakes (or dogs, or heights, or flying, etc.), the diagnosis is rarely in doubt, though several differential diagnostic criteria still need to be considered.

Specific phobias are most common in childhood, though they are also surprisingly prevalent among older adults (LeBeau et al. 2010). It is common for individuals with specific phobia, especially children, to have multiple specific phobias. Whereas individuals with situational, natural environment, and animal specific phobias are likely to describe a typical fear response with autonomic hyperarousal (heart racing, tremor, shortness of breath) in the presence or the anticipation of the phobic stimulus, individuals with blood-injection-injury specific phobia often demonstrate a vasovagal fainting or near-fainting response; this is one of those rare instances where patients with anxiety disorders can actually "pass out," rather than just worry about passing out. On first occurrence, a thorough neurological and cardiac evaluation is recommended to rule out another explanation for the loss of consciousness.

Differential diagnosis with agoraphobia can also be challenging. When the situation^) involve the typical agoraphobic cluster with concerns of being incapacitated in the situation(s), that diagnosis should be applied. Public speaking anxiety is another area where confusion with specific phobia can occur. By definition, public speaking anxiety is considered to be a form of SAD, and in fact, it is mentioned as a specific example of the "performance only" specifier in DSM-5. What unites public speaking anxiety—which otherwise would fit the criteria for specific phobia—with SAD is the content of cognitions: individuals with public speaking anxiety, like other individuals with SAD, are uncomfortable and/or avoid situations involving scrutiny by others, fearing that they will do or say something to embarrass themselves, look stupid, or otherwise be negatively evaluated—all core concerns in SAD.

Some specific phobias develop following a traumatic event (e.g., being bitten by a dog), but most patients with specific phobia do not recall any experiential precursor (e.g., most snake phobics have never been bitten by a snake and most flying phobics have never been in a plane crash). Temperamental factors that are a risk factor for specific phobia, such as neuroticism or behavioral inhibition, are shared with other anxiety disorders (Craske et al. 2009). Although much is known about the brain circuitry and genes involved in fear (Craske et al. 2009), little is known about the specific function of these biological systems in specific phobia.

Case Example

A 36-year-old man was referred to a psychiatrist by his primary care physician after a failed attempt at treating his depression. His family physician had treated him with sertraline up to 100 mg/day with no effect on his depressive symptoms. The patient had reported depressive symptoms on and off since adolescence, but had never sought treatment previously. The current episode was precipitated by a job layoff and the subsequent protracted search for a new job, which was ongoing. The patient, in addition to a history consistent with current major depression without suicidal ideation, reported a history of past alcohol dependence and recent increase in his alcohol use. He also reported, on systematic questioning, having a lifelong history of discomfort in social situations, marked by fear of saying something foolish or being judged as stupid. He further reported that he had been having tremendous difficulty making phone calls as part of his job search and that he had been avoiding setting up job interviews and other networking appointments.

Social anxiety disorder, also known as social phobia, is characterized by a marked fear of social and performance situations that often results in avoidance. The concern in such situations is that the individual will say or do something that will result in embarrassment or humiliation. The core fear in SAD is fear of negative evaluation—that is, the belief that when in situations where evaluation is possible, the individual will not measure up and will be judged negatively (Hofmann et al. 2009).

Median onset of SAD is in the late teens, but there are really two modes of onset: one with onset in the teenage years and the other with onset very early in life. SAD is frequently comorbid with major depression and, in fact, seems to be an antecedent risk factor for its onset among young adults. The course of SAD is typically continuous and lifelong.

Like many other anxiety disorders, SAD is associated with several physical health conditions (Sareen et al. 2006). This comorbidity carries with it a high burden of functional disability that includes decreased workplace productivity, increased financial costs, and reduced health-related quality of life (Sareen et al. 2006; Stein et al. 2011a). Despite the extent of suffering and impairment associated with social phobia, few individuals with the disorder seek treatment, and often only after decades of suffering.

DSM-5 uses the term social anxiety disorder as the preferred diagnostic moniker (rather than social phobia) to emphasize that this is, for the majority of patients, more than just a circumscribed phobia (Bögels et al. 2010). DSM-IV had led with social phobia but had emphasized the existence of a substantial subgroup of patients with pervasive social fears and avoidance, which was termed "generalized" social phobia. Framers of the DSM-5 version elected to delete the "generalized" subtype, instead noting the existence of a newly defined "performance only" sub-type (see DSM-5 criteria for social anxiety disorder [social phobia] in Box 12-4). The effect of this change is (implicitly if not explicitly) to acknowledge that many patients with SAD have extensive social fears that span multiple social situations that are not limited to performance situations (i.e., they would have fallen into the DSM-IV "generalized" subtype), and to identify a subtype ("performance only") where the fears are much more circumscribed in this regard. The rationale for this change was that it was psychometrically difficult to define how many social fears an individual needed to have or how extensive social fears needed to be to apply the "generalized" subtype (which was codified by "most social situations") in DSM-IV. The intent, in part, in making this change in DSM-5 was to increase recognition of the usual pervasiveness of SAD as the norm and to permit the use of the "performance only" subtype to denote a more limited, usually less severe variant, when warranted. The wisdom of this change—which will make it difficult to draw upon 15 years of research focused on the "generalized" form of SAD—remains to be seen.

|

Box 12-4. DSM-5 Criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia) |

|

300.23 (F40.10) |

Note: In children, the anxiety must occur in peer settings and not just during interactions with adults. Note: In children, the fear or anxiety may be expressed by crying, tantrums, freezing, clinging, shrinking, or failing to speak in social situations. Specify if: Performance only |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

Revisions to the SAD criteria also evaluated the comorbidity between SAD and avoidant personality disorder, thought by many researchers to be a severe variant of SAD rather than a qualitatively distinct disorder. However, there are also some indications that avoidant personality disorder shares links with the schizophrenia spectrum (Bögels et al. 2010). Based in part on these findings, it was concluded that although there is a high degree of overlap between persons with severe SAD and avoidant personality disorder, it was premature to collapse these disorders in DSM-5.

Another important refinement to the diagnostic criteria for SAD in DSM-5 is that the criteria no longer require the individual to recognize that his or her fear is excessive. This criterion had apparently been in place in prior versions of DSM to distinguish SAD fears from paranoid fears. But clinicians pointed out that some patients—particularly those who have had lifelong SAD—do not see their fear as excessive but rather as rational and realistic. This was always acknowledged to be the case in DSM-IV as it applied to children (who were thought to lack insight to label their fears as "excessive")/but it has now been extended to acknowledge that many individuals may not appreciate that their ingrained fears and beliefs about the dangerousness of social situations are excessive. This assessment now falls into the hands of diagnosing clinicians, who should judge this criterion on the basis of their understanding of the nature and extent of the individual's beliefs about social anxiety in the context of their developmental stage and culturally appropriate norms.

Another change to the DSM-5 SAD criteria pertains to a DSM-IV clause that had precluded the diagnosis of SAD if the symptoms were related to a physical condition (e.g., Parkinson's disease, obesity, stuttering) that might be expected to be a nidus for social evaluative fears. Numerous studies subsequent to the implementation of DSM-IV have demonstrated that whereas such physical conditions can, indeed, be the basis for social fears and avoidance that result in distress and/or impairment, they are not universally so (Stein and Stein 2008). So, for example, some individuals with stuttering have clinically significant social anxiety symptoms, but many do not. Moreover, paying attention to the social anxiety symptoms in such individuals and, if warranted, providing specific treatment for SAD can be beneficial. Thus, this important change in DSM-5 is anticipated to help clinicians recognize SAD in individuals with various forms of physical illness, and to facilitate the provision of treatment if indicated.

SAD is not especially difficult to diagnose in a clinical context, once an index of suspicion is high enough and appropriate queries are made. A patient who endorses fear and avoidance of social situations because of concerns about embarrassment or humiliation, and who experiences functional impairment and/or considerable distress in relation to these concerns, almost certainly meets diagnostic criteria and may well benefit from treatment. Still, there are several areas in which the differential diagnosis can be somewhat more challenging.

Shyness (i.e., social reticence) spans a range from normative to extreme, and is not in and of itself an indicator of psychopathology. Many persons with SAD do consider themselves to be shy, and many report that their SAD evolved from a background of childhood shyness. When shyness causes extreme distress or is associated with functional disability, then it is likely that appropriate questioning will reveal a diagnosis of SAD.

As noted earlier in this chapter, panic attacks are not unique to panic disorder. They can and do occur in individuals with SAD when faced with situations where they feel scrutinized, or even in anticipation of such situations. Directly asking about the cognitions the individual experiences during or in anticipation of his or her anxiety symptoms (e.g., "What were you thinking about when you felt anxious and uncomfortable?") is essential in differential diagnosis. Patients with SAD attribute their anxiety symptoms to the evaluative situation, whereas patients with panic disorder experience their anxiety symptoms as unexpected or inexplicable.

Social anxiety disorder is frequently comorbid with major depression but should not be diagnosed if social avoidance is confined to depressive episodes. Social fears and discomfort are often part of the schizophrenia syndrome and can, at times—especially in the prodromal stages—be difficult to distinguish from SAD, but other evidence of psychotic symptoms will eventually surface. Eating disorders or obsessive-compulsive disorder may be associated with social evaluative anxiety (e.g., the person is concerned that others will observe and judge them based on their abnormal eating or checking behaviors), but a diagnosis of SAD should only be made if independent social anxiety symptoms co-occur.

Body dysmorphic disorder, which in DSM-5 is classified with the Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, is interesting in that it commonly involves concerns about how the individual will be judged by others. But in the case of body dysmorphic disorder, the concern is that others will negatively evaluate perceived defects or flaws in the individual's physical appearance, whereas in SAD the concern is that others will negatively evaluate the individual's internal self (personality, intelligence, etc.). Not surprisingly, there is considerable comorbidity between SAD and body dysmorphic disorder.

As noted above, avoidant personality disorder will be diagnosable as a comorbid disorder in many patients with SAD, particularly those with diagnoses that do not have the "performance only" specifier (i.e., diagnoses that would have been considered "generalized" in DSM-IV). Therefore, avoidant personality disorder would not be considered an alternative diagnosis, but rather an additional diagnosis that may represent a marker of increased SAD severity (Stein and Stein 2008).

The etiology of SAD is not well understood. But there is emerging an increasing understanding of the disorder as being multifactorially influenced by a variety of biopsychosocial risk factors. SAD shares with the other anxiety disorders the common risk factors of childhood maltreatment and familial risk. Studies of children who are behaviorally inhibited, meaning that they are hesitant to interact with and approach strangers in a variety of laboratory-based experimental paradigms, are at increased risk for developing SAD by adolescence (Hirshfeld-Becker et al. 2008). Observational laboratory studies suggest that parent-to-child transmission of social fears and avoidance can occur as a result of parental modeling, though interactions with innate temperament also are in evidence. Twin studies comparing risk of SAD in monozygotic compared with dizygotic twin pairs demonstrate modest heritability, and family studies suggest that much of the familiality is carried by what was referred to in DSM-IV as the generalized type of SAD (Gelernter and Stein 2009). Genetic studies are still in their infancy, with no well-replicated genes yet detected (Gelernter and Stein 2009).

SAD seems to involve abnormal responding in anxiety circuitry that includes the amygdala and insular cortex, findings that are shared with several other anxiety and trauma-related disorders (Etkin and Wager 2007). Adults with SAD demonstrate a variety of attentional, interpretative, and other cognitive biases (Ouimet et al. 2009), the origins of which are poorly understood but which nonetheless may be a focus for therapeutic interventions, such as those discussed later in this chapter.

Case Example

A 35-year-old Asian American woman was referred to a psychiatrist for assessment of anxiety and avoidance. At this assessment she described an incident 2 years prior to the referral when she woke up one night with chest pains and thought that she was having a heart attack. Accompanying symptoms were shortness of breath, heart racing, sweating, and dizziness. Her family took her to the emergency room, where she received a thorough medical workup. There was no evidence of any cardiac problems. After that day, she stopped driving because of the fear of having chest pains. She was unable to attend her children's sports events, go on buses, or go to church because of her fear. Although the patient was unable to define a specific stressor prior to the onset, a number of stressful life events had occurred before the incident 2 years earlier when she woke up with chest pains; these events included the death of a close friend from cancer and the loss of her husband's job. There was no prior history of emotional problems. There was a past history of asthma. When the patient was 12 years old, her father had died suddenly of a heart attack.

Although panic disorder as a diagnostic entity emerged only in 1980 with the publication of DSM-III, accounts of a clinically similar syndrome appeared much earlier (e.g., soldier's heart; neurocirculatory asthenia) (Wheeler et al. 1950). Along with paroxysmal autonomic nervous system arousal and catastrophic cognitions, these descriptions highlighted symptoms of profound fatigue, not part of current diagnostic criteria (though patients with panic disorder often report extreme fatigue after experiencing an attack). The military contexts in which these syndromes developed implicated a prominent role for stress and trauma, suggesting a possible area of etiological overlap with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), another disorder that often features panic attacks. Panic disorder is the anxiety disorder that has been the most intensively studied over the past three decades; it has led the way in enlarging our understanding of the psychology and neurobiology of anxiety and has helped the medical community and the general public appreciate the extent to which anxiety disorders can be considered a serious public health concern (Roy-Byrne et al. 2006).

Descriptions of panic disorder have changed only slightly between DSM-III and DSM-5, with the essential elements of the syndrome remaining unchanged. The DSM-5 diagnosis of panic disorder (Box 12-5) requires the presence of recurrent panic attacks along with either 1) worry about the possibility of future attacks or 2) development of phobic avoidance—staying away from places or situations the individual fears may elicit a panic attack or where escape or obtaining help in the event of an attack would be unlikely or difficult (e.g., driving on a bridge or sitting in a crowded movie theater)—or other change in behavior due to the attacks (e.g., frequent visits to the doctor because of concerns about undiagnosed medical illness). Panic attacks are sudden, at least sometimes unexpected episodes of severe anxiety (they may become more context specific and less unexpected over time), accompanied by an array of physical (e.g., cardiorespiratory, otoneurological, gastrointestinal, and/or autonomic) symptoms (see DSM-5 specifier for panic attack in Box 12-6). These attacks are extremely frightening, particularly because they seem to occur out of the blue and without explanation. The attacks are so aversive that the individual may avoid places or situations where prior attacks occurred (e.g., a shopping mall or supermarket), or where escape would be difficult (e.g., driving a car on a freeway) or embarrassing (e.g., sitting in a movie) in the event of an attack. At times, the individual may fear that a panic attack is a heart attack, and may make recurrent visits to the emergency room seeking medical care. The individual may also become especially focused on his or her own physiology, being alert to changes in heart or respiratory rate that he or she believes—from experience of prior attacks—might herald a panic attack and avoiding activities (e.g., exercise) that might reproduce these feelings.

|

Box 12-5. DSM-5 Criteria for Panic Disorder |

|

300.01 (F41.0) |

Note: The abrupt surge can occur from a calm state or an anxious state. Note: Culture-specific symptoms (e.g., tinnitus, neck soreness, headache, uncontrollable screaming or crying) may be seen. Such symptoms should not count as one of the four required symptoms. |

|

Box 12-6. DSM-5 Panic Attack Specifier |

|

Note: Symptoms are presented for the purpose of identifying a panic attack; however, panic attack is not a mental disorder and cannot be coded. Panic attacks can occur in the context of any anxiety disorder as well as other mental disorders (e.g., depressive disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders) and some medical conditions (e.g., cardiac, respiratory, vestibular, gastrointestinal). When the presence of a panic attack is identified, it should be noted as a specifier (e.g., "posttraumatic stress disorder with panic attacks"). For panic disorder, the presence of panic attack is contained within the criteria for the disorder and panic attack is not used as a specifier. An abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that reaches a peak within minutes, and during which time four (or more) of the following symptoms occur: Note: The abrupt surge can occur from a calm state or an anxious state.

Note: Culture-specific symptoms (e.g., tinnitus, neck soreness, headache, uncontrollable screaming or crying) may be seen. Such symptoms should not count as one of the four required symptoms. |

Over time—and the time period may be from days to months to years—the experience of recurrent panic attacks in multiple situations may lead the individual to curtail many activities in an effort to prevent panic attacks from occurring in such situations. It is this pervasive phobic avoidance—which carries the diagnostic label agoraphobia (discussed in more detail later in this chapter)—that often leads to the extensive disability seen with panic disorder. Interestingly, however, the extent of phobic avoidance can vary widely between individuals, and the factors that influence this variation are largely unclear (Hofmann et al. 2009).

Whereas in DSM-IV the co-occurrence of panic disorder and agoraphobia was labeled with a single diagnosis (i.e., panic disorder with agoraphobia), DSM-5 has diagnostically decoupled these two entities (i.e., there are separate diagnoses for panic disorder and for agoraphobia). Although it is to be expected that panic disorder and agoraphobia will co-occur frequently (about two-thirds of the time), the diagnoses were decoupled to draw attention to the fact that agoraphobia not infrequently occurs without a history of panic disorder.

Not all panic attacks, even when recurrent, are indicative of panic disorder. Panic attacks can occur in individuals with specific phobias when exposed to the feared object (common examples are heights, snakes, and spiders) or in individuals with SAD when faced with (or in anticipation of) situations where they may be scrutinized. The difference in such situations is that the individual is keenly aware of the source of their fearful sensations, whereas in panic disorder these same types of sensations are experienced as unprovoked, unexplained, and often occurring "out of the blue." Panic attacks can also occur in individuals with PTSD, where exposure to reminders of a traumatic event can trigger such attacks and can be especially difficult to discern as such, unless a careful history of prior traumatic experiences is taken.

Because panic disorder mimics numerous medical conditions, patients often have increased utilization of health care, including physician visits, procedures, and laboratory tests (Kroenke et al. 2007). New to DSM-5 is the diagnostic entity illness anxiety disorder, which retains elements of its predecessor, DSM-IV hypochondriasis, applying to individuals who are preoccupied with having or acquiring a serious illness. Persons with panic disorder frequently have the belief that their intense somatic symptoms are indicative of a serious physical illness (e.g., cardiac or neurological). This is particularly true early on in the course of their illness and in situations where they fail to get good care that includes appropriate diagnosis and education about their condition. In illness anxiety disorder, however, there is the belief that an illness is present without the experience of strong somatic symptoms.

Panic disorder is often associated with comorbid medical problems (Sareen et al. 2006). Conditions such as mitral valve prolapse, asthma, Meniere's disease, migraine, and sleep apnea can accentuate panic symptoms—or be accentuated by them—but these co-occurring conditions would rarely, if ever, be considered the "cause" of an individual's panic attacks. In contrast, panic attacks (and, when recurrent, panic disorder) can occur as a direct result of common conditions such as hyperthyroidism and caffeine and other stimulant (e.g., cocaine, methamphet-amine) use/abuse, and more rarely with disorders such as pheochromocytoma or partial complex seizures. In most instances, a thorough medical history, physical examination, routine electrocardiogram, thyroid-stimulating hormone blood level, and urine or blood drug screen are sufficient as a first-pass "rule out" for such conditions. But when history dictates, additional tests may be indicated (e.g., frequent palpitations indicating the need for a Holter monitor, echocardiogram, and/or cardiology consultation; profound confusion during or after attacks indicating the need for an electroencephalogram and/or neurology consultation). Importantly, although a diagnosis of panic disorder can be considered definitive without needing to rule out every rare medical condition with which it can be confused or comorbid, it is incumbent on the physician to revisit the medical differential diagnosis if the course of illness changes, if symptoms become atypical, or, critically, if the patient does not respond well to standard treatments.

Data from a prospective population-based survey in the Netherlands show a strong association between panic disorder (and anxiety disorders in general) and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, even after adjusting for affective comorbidity and other suicide risk factors (Sareen et al. 2005). Given these observations, clinicians should be vigilant to the likelihood that their patients with panic disorder are at increased risk for suicide. Panic attacks are increasingly being so well recognized in certain medical settings, such as the emergency room, that it is now common practice to identify them appropriately as such, provide reassurance, and send the patient home. It is incumbent on clinicians in these settings to inquire about comorbid depression, in general, and suicidal ideation and plans, in particular. It is the "anxious depressed" patient who is at very high risk for suicide, compared with the patient who is melancholic and has psychomotor retardation, and it is the patient with panic disorder who should not be overlooked in this regard.

Without treatment, panic disorder tends to follow a relapsing and remitting course. Only a minority of patients remit without subsequent relapse within a few years, although a similar number experience notable improvement (albeit with a waxing and waning course).

The etiology of panic disorder is not well understood. But research over the past several decades continues to inform our understanding of the biological and psychological contributors to the development and maintenance of panic disorder. A substantial body of epidemiological evidence has investigated risk factors for panic disorder. As with most psychiatric disorders, a "stress-diathesis" model is commonly used to explain the genesis and maintenance of panic disorder. Studies have suggested that early life trauma or maltreatment (Stein et al. 1996) is an important risk factor, although this risk is not unique to panic disorder, extending to other anxiety and depressive disorders as well as to dissociative and certain personality disorders. Stressful life events likely contribute to the timing of onset as well as the maintenance of the disorder. Studies have implicated cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence as a risk factor for later onset of panic disorder (Cosci et al. 2010).

Genetics. Twin studies suggest that panic disorder is moderately heritable (~ 40%) (Gelernter and Stein 2009). From a genetic perspective, it is believed that panic disorder, like other psychiatric disorders, is a complex disorder with multiple genes conferring vulnerability through as-yet largely undetermined pathways (Manolio et al. 2009; Smoller et al. 2009).

Although a number of family-based (e.g., linkage) and other genetic (e.g., association) studies have been conducted in panic disorder, robust and replicated findings have been few to date (Schumacher et al. 2011). However, some promising leads have emerged (Logue et al. 2012). For example, several studies have implicated the adenosine 2A receptor gene (ADORA2A) as having a possible role in panic disorder, consistent with the anxiogenic effects of caffeine, a known antagonist at this receptor (Hohoff et al. 2010). Association studies examining genes involved in other neurotransmitter systems thought to be associated with fear and anxiety (e.g., norepinephrine and serotonin) have produced inconsistent, often nonreplicated results. The most consistent results have involved the 22qll catechol O-methyl-transferase gene (COMT) that codes for the enzyme responsible for norepinephrine metabolism.

Although these investigations have been limited by our lack of understanding of the pathophysiology of panic disorder and our inability to identify the most heritable phenotype(s) of the illness, the failure to replicate some genetic associations is a problem that is by no means unique to panic disorder. Instead, this failure reflects inherent limitations in the extant genetic approaches to studying complex genetic diseases (Manolio et al. 2009).

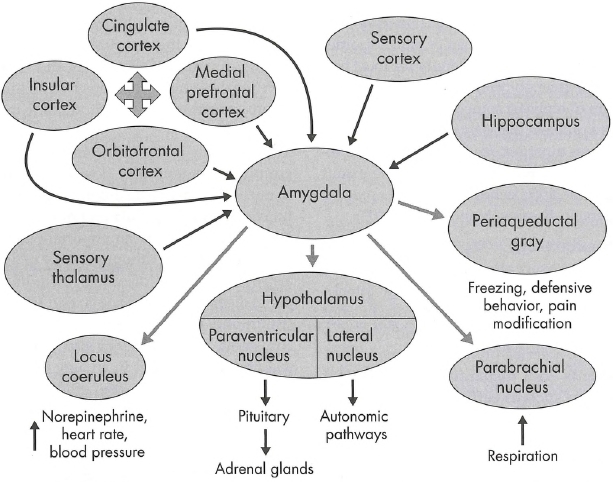

Neurobiology. Beginning in 1967 with Pitt's observation that hyperosmolar sodium lactate provoked panic attacks in patients with panic disorder but not in control subjects (Pitts and McClure 1967), a series of studies showed that agents with disparate mechanisms of action such as caffeine, isoproterenol, yohimbine, carbon dioxide, and cholecystokinin (CCK) had similar abilities to provoke panic in patients with panic disorder but not in control subjects (Roy-Byrne et al. 2006). Many of these neuro-biological "challenge" agents have been thought to have specific effects on the brain's fear circuits, which are believed to function aberrantly in patients with panic disorder. Figure 12-1 depicts the proposed systems and their role in panic disorder. The studies of these challenge agents were originally proposed to indicate specific biochemical abnormalities in panic disorder. However, many investigators now agree that most of the effects elicited by these compounds can be explained on the basis of learning theories of panic disorder (see the next section, "Psychology"), which emphasize that patients with panic disorder misinterpret and are frightened by perceived perturbations in their physiological state. As a case in point, whereas heightened brain sensitivity to elevated carbon dioxide has been a long-standing prominent theory for the etiology of panic disorder, a recent study showed that patients could be taught to chronically raise or lower their partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PC02) levels and that either of these manipulations resulted in improvement in panic symptoms (Kim et al. 2012).

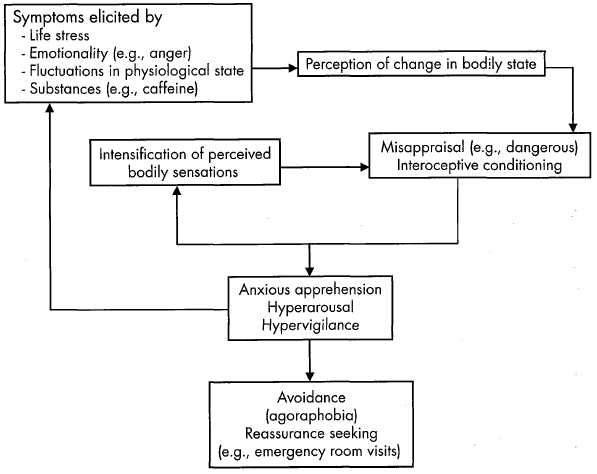

Alterations in the functioning of fear circuitry are generally posited across many of the anxiety disorders, with dysfunction in the amygdala and its connections believed to play an important etiological role in the pathophysiology of an array of fear-based disorders, including panic disorder, social phobia, and PTSD (Etkin and Wager 2007; Figure 12-2). Amygdala dysfunction may also be a critical underlying factor in anxiety proneness more generally (Stein et al. 2007). Functional neuroimaging data suggest that a particular brain structure, the insula, is involved in the intense awareness of somatic sensations experienced by patients with panic disorder and related disorders (Paulus and Stein 2010). The emergence of these data heralds much closer ties between "psychological" and "biological" theories of panic disorder in the years to come.

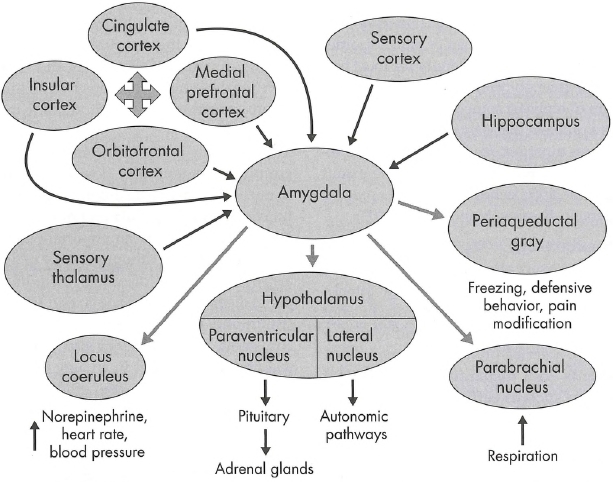

Psychology. Psychodynamic theories of panic disorder, which tend to emphasize underlying issues with anger and conflict, continue to hold some sway but have been relatively little studied empirically (Busch and Milrod 2009). Learning theory postulates that factors that increase the salience of bodily sensations are central to the onset and maintenance of panic disorder. One such factor is anxiety sensitivity, the belief that anxiety-related sensations are harmful. Individuals who score high on anxiety sensitivity are at increased risk for the experience of panic attacks and for the development of panic disorder.

Heightened anxiety sensitivity is probably multifactorial, with studies suggesting that it may be acquired from recurrent direct aversive experiences (e.g., childhood maltreatment, physical illness such as asthma), vicarious observations (e.g., significant illnesses or deaths among family members), or parental reinforcement or modeling of distressed reactions to bodily sensations. These factors may contribute to a heightened state of interoceptive attention (attention to internal sensations) that primes the individual to experience panic attacks and to be intensely frightened by them when they occur. "Fear of fear" develops after the initial panic attacks and is believed to be the result of interoceptive conditioning (conditioned fear of internal cues such as pounding heart) and the subsequent mis-appraisal of these internal cues as indicating something threatening or dangerous (e.g., loss of control; heart attack or stroke) (Bouton et al. 2001).

Figure 12-1. Proposed neural circuitry of panic.

The amygdala has a crucial role as an anxiety way-station that mediates incoming stimuli from the environment (thalamus and sensory cortex) and stored experience (frontal cortex and hippocampus; dark arrows), thereby affecting the anxiety and panic response by stimulating various brain areas responsible for key panic symptoms (.lighter arrows). The periaqeductal gray in the midbrain could be especially important for mediating panic-anxiety. Drug treatments can target all parts of this system, affecting amygdala and frontal-lobe interpretation of stimuli, or output effects. Cognitive-behavioral treatment affects the frontal-lobe areas, especially in the medial prefrontal cortex, which is known to inhibit input to the amygdala by using a braking action.

Source. Reprinted from Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB: "Panic Disorder." Lancet 368(9540):1023-1032, 2006. Copyright 2006, Elsevier Ltd. (available at: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014067360669418X). Used with permission.

Figure 12-3 illustrates the cycle of cognitive distortions and behavioral changes seen in panic disorder. It is this theoretical model that underlies the application of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to this disorder (Meuret et al. 2012).

Figure 12-2. Clusters in which significant hyperactivation or hypoactivation was found in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia relative to comparison subjects and in healthy subjects undergoing fear conditioning.

To view this figure in color, see Plate 6 in Color Gallery in middle of book.

Results are shown for the amygdalae (A) and insular cortices (B). Note that within the left amygdala there were two distinct clusters for PTSD, a ventral anterior hyperactivation cluster and a dorsal posterior hypoactivation cluster. The right side of the image corresponds to the right side of the brain.

Source. Reprinted from Etkin A, Wager TD: "Functional Neuroimaging of Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Processing in PTSD, Social Anxiety Disorder, and Specific Phobia." American Journal of Psychiatry 164(10):1476-1488, 2007. Copyright 2007, American Psychiatric Association. Used with permission.

Case Example

A 34-year-old man describes a 5-year history of avoidance of malls and movie theaters. He describes an episode where he became physically ill, with vomiting and dizziness at a restaurant. He was quite embarrassed and since then he has become anxious in many situations. He avoids crowds, buses, movie theaters, and malls. Due to anxiety, he will only go shopping with a family member present. He can't attend his son's sports activities because of his anxiety. His wife and his children are quite frustrated with him.

Agoraphobia literally, in Greek, means "fear of the marketplace." Whereas large shopping venues certainly can be among the situations avoided by persons with agoraphobia, Criterion A of the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for agoraphobia (Box 12-7) refers to marked fear or anxiety about two or more of the following five situations: 1) using public transportation, 2) being in open spaces, 3) being in enclosed places, 4) standing in line or being in a crowd, or 5) being outside of the home alone. What ties these types of situations together under the syndrome of agoraphobia is the person's fear of being incapacitated or unable to escape or obtain help should certain symptoms (e.g., dizziness, heart racing, trouble concentrating) occur in these situations. The agoraphobic situations are actively avoided, require the presence of a companion, or are endured with intense fear or anxiety.

Figure 12-3. Cognitive and behavioral factors in panic disorder.

Source. Adapted from Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB: "Panic Disorder." Lancet 368(9540):1023-1032, 2006. Used with permission.

|

Box 12-7. DSM-5 Criteria for Agoraphobia |

|

300.22 (F40.00) |

Note: Agoraphobia is diagnosed irrespective of the presence of panic disorder. If an individual's presentation meets criteria for panic disorder and agoraphobia, both diagnoses should be assigned. |

As noted earlier in the "Panic Disorder" section, agoraphobia is a common consequence of panic disorder. But agoraphobia can also occur without panic disorder, and although this has long been known to be the case, the decision to decouple agoraphobia from panic disorder in DSM-5 reflects, in part, the recognition that this is not an uncommon scenario (e.g., 12-month prevalence of agoraphobia without panic disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication is 0.8%; Kessler et al. 2012). Furthermore, the presumed causal evolution from panic disorder to agoraphobia—inherent in the DSM-IV conceptualization of the two disorders—has not been upheld. Whereas a baseline diagnosis of panic disorder is a strong predictor of subsequent agoraphobia, it is also true that a baseline diagnosis of agoraphobia without spontaneous panic attacks is a predictor of subsequent panic disorder (Bienvenu et al. 2006).

Agoraphobia can be among the most disabling of the anxiety disorders. It can range in severity from avoidance of driving on busy freeways during rush hour to requiring a companion when venturing outside the home to being completely homebound. Dependence on others (e.g., to chauffeur children, to do shopping, to get to and from work) frequently results. The extent of these phobic limitations may fluctuate over time. Whereas agoraphobia can begin at any age, it typically has its onset many years later than other phobias and, unlike most other anxiety disorders, can surface in the elderly. In cases of onset in late adulthood, agoraphobia can often be understood as an anxiety-based complication of physical limitations. For example, an individual who has experienced several episodes of vertigo might develop a fear of driving or walking without assistance, even when the vertiginous bouts subside. When fear and avoidance exceed the actual dangers posed to an individual in performing certain activities, even if the fears have (or had) a basis in genuine physical limitations, a diagnosis of agoraphobia may be applicable.

Differential diagnosis of agoraphobia from specific phobia is not always easy. On their own, any of the situations within the typical agoraphobic clusters (see DSM-5 diagnostic criteria in Box 12-7) could be considered a specific phobia, if it were truly specific (i.e., isolated to that particular situation). But what ties them together under agoraphobia is the fact that the individual will have several fears from these clusters of situations, accompanied by the aforementioned prototypical fears of being incapacitated, unable to escape, or unable to obtain help if symptoms emerge. So-called driving phobia will often, upon more systematic questioning, prove to be merely one of several other transportation-related phobias that reveal a diagnosis of agoraphobia. Another difficult differential diagnosis can be with PTSD, where an individual may have multiple feared situations from the agoraphobia clusters, including leaving home; but in PTSD, the fears and avoidance are tied to memories of specific traumatic experiences, which are typically absent in agoraphobia. SAD and agoraphobia can both be associated with fear and avoidance of similar types of situations (e.g., crowds), but the nature of the cognitions differs. Individuals with social phobia will report that they avoid situations because of fear of embarrassment or humiliation, whereas individuals with agoraphobia will report that they avoid situations because of fear of incapacitation or difficulty in escaping should help not be available.

The etiology of agoraphobia, particularly as distinct from panic disorder, is not well understood. As already noted, many cases of agoraphobia are considered to be a complication of panic disorder, wherein repeated panic attacks—which are highly aversive—lead to fear and avoidance of situations in which the attacks have occurred or are considered likely to occur. But there are also many cases of agoraphobia where no antecedent history of spontaneous panic attacks can be elicited. Although some of these cases may stem from a history of physical illness (e.g., vertigo) or other physical limitations (e.g., postural instability in Parkinson disease) that serve to render the individuals fearful and concerned about their own ability to function in certain situations, such a history is absent in many—especially younger—individuals with agoraphobia.

Case Example

A 34-year-old woman works as a sous-chef at a restaurant. She is referred to a psychiatrist by her family physician for treatment of depression. When seen, she reports being chronically tense, nervous, and readily upset by a variety of life stressors. She worries that she will lose her job because of her inability to perform to the expected standard of her boss (though he has never expressed to her that he is dissatisfied with her work), and that she will spiral into penury and homelessness. She becomes tearful when relaying this information. On further questioning, she admits to many worries beyond her work and her finances, including her own health and that of her dog, and more nonspecific concerns (e.g., about the state of the world economy). She further describes a long history of initial insomnia, describing how she lies in bed and rehashes the day's events and the next day's anticipated tribulations. Although her mood has been worse in the past 3-4 months, the nervousness, worries, and insomnia have gone on "for years."

Generalized anxiety disorder is characterized by nervousness, somatic symptoms of anxiety, and worry. The name of the disorder has drawn criticism for its propensity to be referred to by some practitioners as general anxiety disorder, leading to the assumption that all forms of anxiety fall under the diagnostic label generalized anxiety disorder (referred to in this chapter as GAD; see DSM-5 criteria for GAD in Box 12-8). Whereas nervousness, physical symptoms, and focal worries are indeed seen in virtually all of the anxiety disorders, what distinguishes GAD is the multifocal and pervasive nature of the worries. Individuals with GAD have multiple domains of worry; these might include finances, health (their own and that of their loved ones), safety, and many others (Bienvenu et al. 2010). Consideration was given to changing the name of this disorder in DSM-5 to generalized worry disorder or generalized anxiety and worry disorder, but it was ultimately decided to leave the name as is.

|

Box 12-8. DSM-5 Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

|

300.02 (F41.1) |

Note: Only one item is required in children. |

GAD is encountered much more frequently by primary care physicians and other medical practitioners than by psychiatrists (Kroenke et al. 2007). This is because GAD typically presents with somatic symptoms (e.g., headache, back pain and other muscle aches, gastrointestinal distress) for which sufferers seek help in the primary care setting. Insomnia is another common complaint in GAD for which patients may seek help in primary care, and it is one of the symptoms that can first lead practitioners to apply a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). Whereas initial insomnia is somewhat more typical of GAD and later insomnia with early-morning awakening is more typical of MDD, either can occur and, in fact, GAD and MDD very frequently co-occur. GAD has a later modal age of onset than the other anxiety disorders and is fairly unique among the anxiety disorders in its relatively higher incidence in late life (Poren-sky et al. 2009).

The diagnosis of GAD is made when an individual reports characteristic chronic symptoms of nervousness, somatic symptoms, and worry. Although several studies had suggested that persistence of symptoms for 1-3 months was associated with a similar course, comorbidity, and functional impairment as persistence for 6 or more months (Andrews et al. 2010), DSM-5 retained the 6-month minimum duration for diagnosis.

Although GAD is not solely a diagnosis of exclusion, it is important to rule out other conditions that may present with GAD-like symptoms. Foremost among these is MDD, which is often associated with nervousness, physical symptoms, and ruminative worries (although the worries tend to be more self-blameful in MDD). GAD and MDD can co-occur, but both diagnoses should generally only be made when there is fairly clear evidence of independent evolution of symptoms. For example, an individual who has had several years of typical GAD symptoms may subsequently develop marked worsening of mood, loss of interest, and thoughts of suicide. That type of presentation would warrant the dual diagnoses of GAD and MDD. In contrast, the onset of worry, nervousness, tearfulness, and suicidal ideation in a previously healthy individual would usually be best explained by the single diagnosis of MDD (although the presence of prominent anxiety symptoms—making this an "anxious depression"—should be noted, as anxious depression and MDD may have differential prognostic and treatment significance) (Andreescu et al. 2007; Fava et al. 2008).

GAD may also co-occur with alcohol and other substance use disorders; when the chronology of symptom onset in relation to substance use is unclear, sometimes only a protracted course of abstinence can separate GAD from the effects of the substance use itself. GAD worries can usually be distinguished from obsessive ruminations that are part of obsessive-compulsive disorder by the more ego-dystonic and, at times, unusual concerns seen in the latter disorder. Health worries in GAD may completely overlap with those that can be attributed to illness anxiety disorder, but the latter is to be diagnosed only if the concerns are solely health related. If health-related concerns are only one of multiple domains of worry, the diagnosis of GAD should be applied. Like panic disorder, GAD-like symptoms can be caused by some physical ailments (e.g., hyperthyroidism) and substances (e.g., excess caffeine use; stimulants); these possibilities should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Twin studies suggest that GAD is influenced by genetic factors that overlap extensively with those for the personality trait neuroticism (Hettema et al. 2004). Interestingly, the high comorbidity between MDD and GAD is also believed to be attributable, at least in part, to similar genetic but different environmental risk factors. No specific genes have been reliably associated with GAD, but several candidates have been identified, including genes such as COMT, thought to contribute to genetic risk shared across a range of anxiety disorders and related phenotypes, such as neuroticism (Hettema et al. 2008).

There have been relatively few functional neuroimaging studies in GAD, but there is some evidence of failure of anterior cingulate activation and connectivity with the amygdala during implicit regulation of emotional processing in GAD (Etkin et al. 2009). It is unclear if these types of cross-sectional findings represent evidence of biological risk or correlates of the specific psychopathology.

Four additional anxiety disorder diagnostic categories are provided in DSM-5. Substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder is characterized by prominent symptoms of panic or anxiety that are presumed to be due to the effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication, or a toxin) ([American Psychiatric Association 2013]; see Box 12-9 for DSM-5 diagnostic criteria).

|

Box 12-9. DSM-5 Criteria for Substance/Medication-Induced Anxiety Disorder |

The symptoms precede the onset of the substance/medication use; the symptoms persist for a substantial period of time (e.g., about 1 month) after the cessation of acute withdrawal or severe intoxication; or there is other evidence suggesting the existence of an independent non-substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder (e.g., a history of recurrent non-substance/medication-related episodes). Note: This diagnosis should be made instead of a diagnosis of substance intoxication or substance withdrawal only when the symptoms in Criterion A predominate in the clinical picture and they are sufficiently severe to warrant clinical attention. Specify if (see Table 1 [p. 482] in the DSM-5 chapter "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" for diagnoses associated with substance class): With onset during intoxication With onset during withdrawal With onset after medication use |

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

Anxiety disorder due to another medical condition is characterized by clinically significant anxiety that is judged—on the basis of evidence from the history, physical examination, and/or laboratory findings—to be best explained as the direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition, such as thyroid disease or temporal lobe epilepsy (American Psychiatric Association 2013; see Box 12-10 for DSM-5 diagnostic criteria).

|

Box 12-10. DSM-5 Criteria for Anxiety Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition |

|

293.84 (F06.4) |

|

NOTICE. Criteria set above contains only the diagnostic criteria and specifiers; refer to DSM-5 for the full criteria set, including specifier descriptions and coding and reporting procedures.

Finally, the categories other specified anxiety disorder and unspecified anxiety disorder may be applied to presentations in which symptoms characteristic of an anxiety disorder are present and cause clinically significant distress or impairment but do not meet full criteria for any specific anxiety disorder (American Psychiatric Association 2013). For an "other specified" diagnosis (Box 12-11), the clinician provides the specific reason that full criteria are not met; for an "unspecified" diagnosis (Box 12-12), no reason need be given.

|

Box 12-11. DSM-5 Other Specified Anxiety Disorder |

|

300.09 (F41.8) |

|

This category applies to presentations in which symptoms characteristic of an anxiety disorder that cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning predominate but do not meet the full criteria for any of the disorders in the anxiety disorders diagnostic class. The other specified anxiety disorder category is used in situations in which the clinician chooses to communicate the specific reason that the presentation does not meet the criteria for any specific anxiety disorder. This is done by recording "other specified anxiety disorder" followed by the specific reason (e.g., "generalized anxiety not occurring more days than not"). Examples of presentations that can be specified using the "other specified" designation include the following:

|

|

Box 12-12. DSM-5 Unspecified Anxiety Disorder |

|

300.00 (F41.9) |

|

This category applies to presentations in which symptoms characteristic of an anxiety disorder that cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning predominate but do not meet the full criteria for any of the disorders in the anxiety disorders diagnostic class. The unspecified anxiety disorder category is used in situations in which the clinician chooses not to specify the reason that the criteria are not met for a specific anxiety disorder, and includes presentations in which there is insufficient information to make a more specific diagnosis (e.g., in emergency room settings). |

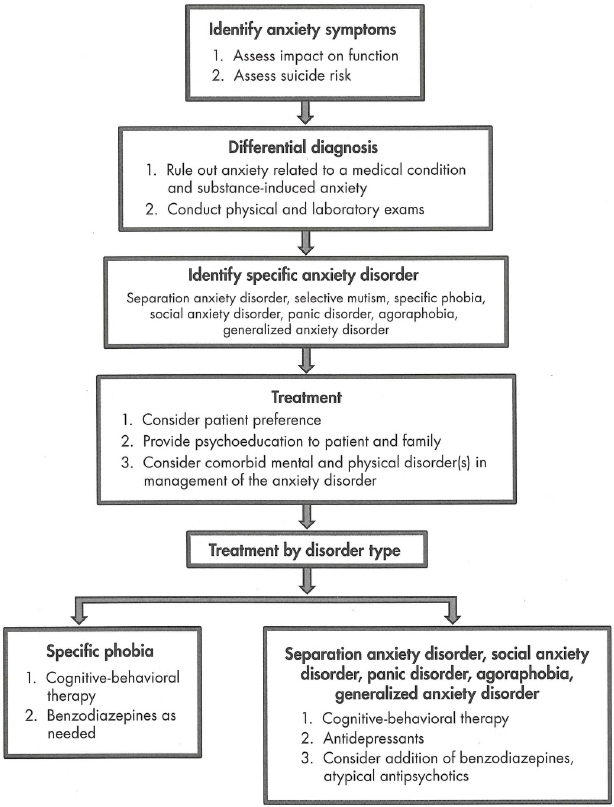

Treatment of anxiety disorders can be extremely gratifying for clinicians because anxiety disorders tend to respond well to psychological and pharmacological treatments. Most patients with anxiety disorders can be well managed in the primary care setting, with only the more difficult-to-treat cases necessitating care in the mental health specialty setting. Figure 12-4 illustrates a general approach. A careful, comprehensive assessment of the anxiety symptoms, disability, presence of any comorbid mental and physical conditions, patient preferences for treatment, and access to evidence-based psychotherapies is important. Detailed assessment of the troubling anxiety symptoms, the key catastrophic cognitions, and the avoidance strategies used by the particular patient is critical to comprehensive treatment planning. Measuring symptoms through panic diaries, worry diaries, or the use of self-report standardized scales (e.g., Overall Anxiety Severity and Interference Scale [OASIS]; Campbell-Sills et al. 2009) help both the patient and therapist track the course and severity of the anxiety problems and are indisputable aids to treatment.

Presence of current comorbidity with other mental disorders such as mood, substance use, and personality disorders (e.g., borderline) also affects the management of anxiety disorders. If the individual is severely depressed, it is important to prioritize treatment of the depression, usually with a combination of medications and therapy, at the same time as attending to the anxiety symptoms. If a bipolar disorder is comorbid with the anxiety disorders), this may affect the type of medications used (e.g., possible need for mood stabilizers) for the treatment of the anxiety disorder(s). Alcohol and substance use disorders are often comorbid with anxiety disorders. Self-medication with alcohol and drugs to reduce tension and anxiety is common among people with anxiety disorders. Understanding the vicious cycle of anxiety symptoms, in which self-medication with alcohol and drugs leads to a rebound of anxiety, is important for both the patient and the clinician. Whereas in the past recommendations were to insist on abstinence before treating comorbid anxiety and substance use disorders, current thinking favors the concurrent treatment of both disorders whenever feasible.

Most patients prefer treatment of anxiety with psychotherapy alone or in combination with medications (Roy-Byme et al. 2010). However, evidence-based psychotherapies administered by therapists well trained and experienced in those psychotherapies may not be readily accessible by all patients in all settings. Thus, medication treatment, which is more often available and covered by insurance, frequently becomes the de facto treatment of anxiety disorders. Even in such circumstances, however, it should be possible to optimize the care of patients receiving pharmacotherapy by the use of appropriate educational, motivational, and behavioral instructions and resources (see the section "Pharmacotherapy" later in this chapter).

Figure 12-4. Algorithm for the treatment and management of anxiety disorders.

Among the psychosocial interventions for anxiety disorders, CBT has the most robust, evidence for efficacy and has been delivered in a variety of formats (individual, group, bibliotherapy, telephone based, computerized). CBT strategies for the various anxiety disorders differ somewhat in their focus and content, but despite this disorder-specific tailoring they are similar in their underlying principles and approaches (Craske et al. 2011). All CBT strategies have the following core components: psychoeducation, relaxation training, cognitive restructuring, and exposure therapy.

Psychoeducation involves having the patient read material about the normal and abnormal nature of anxiety that enhances their understanding of the sources and meanings of anxiety. The cognitive model of anxiety disorders proposes that people with these disorders overestimate the danger in a particular situation and underestimate their own capacity to handle the situation. People with anxiety disorders often have catastrophic automatic thoughts in triggering situations. Patients are taught to become aware of these thoughts that precede or co-occur with their anxiety symptoms, and they learn to challenge these thoughts and change them (cognitive restructuring). The behavioral model of anxiety disorders suggests that individuals respond to external and internal triggers that lead to a sense of danger. The sense of danger leads to a fight-or-flight response and they avoid the triggering situation. Behavioral treatments of anxiety disorders aim to expose the individual to the anxiety-provoking situation and prevent the response of avoidance. Through systematic desensitization, patients gradually but in increasingly more challenging situations face the phobic stimuli that make them feel anxious. Other techniques in CBT include relaxation training through deep muscle relaxation and/or breathing management.