Chapter 2

Delirium and Dementia

Introduction

Having considered the three major areas of cognition with a distributed neural basis—attention, memory, and executive function—it is now appropriate to describe briefly delirium and dementia, which almost invariably affect one or more of these cognitive domains. Patients with one, or both, of these conditions constitute the commonest presentation in behavioural neurology and in geriatric psychiatry.

Delirium

Delirium may be defined as a transient organic mental syndrome of acute onset, characterized by marked attentional abnormalities, impairment in global cognitive functions, perceptual disturbances, increased and/or decreased psychomotor activity, a disordered sleep–wake cycle, and a tendency to marked fluctuations (see Box 2.1).

Several components of this definition deserve further comment. Although delirium is a syndrome with certain core characteristics, the clinical manifestations may vary widely. The features vary between patients and often in a single patient over the course of 24 hours. The onset is always acute or subacute, occurring over hours or days and often at night. The total duration rarely exceeds weeks. The prognosis clearly depends upon the aetiology but if the underlying cause is cured then a complete recovery can be expected. The aspects of cognition principally involved are those with a distributed cerebral basis—attention, memory, and higher-order executive functions (for example, planning, problem-solving, abstraction, sequencing, etc.). Deficits of the more localized cognitive functions, such as language and praxis, may also be seen; but the distributed-function deficits always dominate. Clouding of consciousness is no longer included in contemporary definitions of delirium, for the reasons discussed later in this chapter.

Attention and memory

A disturbance in attention is the most striking and consistent abnormality: patients are unable to generate and sustain attention to external stimuli, and have problems with shifting attention appropriately. They appear distractible, and easily lose the thread of conversations. Accordingly, there is severe impairment on tests requiring sustained concentration and the manipulation of material, such as serial subtraction of 7s, recitation of the months of the year or days of the week in reverse order, and digit span. Another good test for sustained attention is the ability to generate words beginning with certain letters (for example, F, A, and S) or from specific semantic categories (for example, animals, fruit, etc.). Patients with impaired attention produce few exemplars, tend to perseverate, and revert to a previous category.

| Box 2.1 Features of delirium (acute confusional state) |

|

Disorientation in time is almost always present at some time during the illness. Disturbed appreciation of the passage of time is universal. Disorientation for place, and still later for person, may follow with worsening of perceptual and cognitive organization.

The disturbance in memory is largely secondary to diminished attention. Incoming sensory material is poorly attended to and registered. Immediate repetition of a name and address is characteristically defective, and patients need multiple presentations before simple material is repeated correctly. Confabulatory responses may be seen. Retrograde memory is reasonably intact if the patient’s attention can be focused and sustained. On recovery from delirium there is typically a dense amnesic gap for the period of the illness, although where fluctuation has been marked, islands of memory may remain.

Thinking

The organization and content of thought processes are invariably affected in delirium. Even in mild cases there is difficulty in formulating complex ideas and sustaining a logical train of thought. Attempts at history taking reveal the muddled, illogical, and disjointed nature of the patient’s thinking. The capacity to select thoughts and maintain their organization and sequence for the purpose of problem-solving and planning is drastically reduced. Concept formation is impaired, with a tendency to concrete thinking. These deficits are apparent on bedside testing of proverb interpretation, similarity judgement, generation of word definitions, and category fluency.

The content of thought may be dominated by the patient’s concerns, wishes, and fantasies. There is often a dream-like quality to the patient’s thinking. Delusions (i.e. false beliefs incongruent with the patient’s cultural and educational background) are often present. These are usually fleeting, poorly elaborated, and inconsistent. A paranoid persecutory content is most common. For instance, patients may believe that they are about to be killed by the nurse or doctors, or that close family members have been murdered. Delusions, illusions, and hallucinations frequently occur together.

Disorders of perception

Perception in this context refers to the ability to extract information from the environment and one’s own body and to integrate it in a meaningful way. Attentional processes play a crucial role in the perception of sensory information, and the ubiquitous attentional disorder seen in delirium probably underlies many of the perceptual disturbances seen. Vision and hearing are most commonly affected. Disturbance of vision may lead to micropsia, macropsia, or distortions of shape and position, fragmentation, apparent movement, or autoscopy (the perception of seeing oneself from outside the body). Sounds may be accentuated or distorted. Body image may be affected, causing a perceived alteration of size, shape, or position. Bizarre reduplicative phenomena may be reported—for example, when the patient believes that there are two identical hospital wards and they are being moved from one to the other. Feelings of depersonalization and unreality are very common.

Illusions—the misperception of external stimuli—are frequent, and most often involve the visual modality. Patients may mistake spots on the wall for insects, or patterns on the bed-cover for snakes. Illusions may be interwoven with delusions, so that ward sounds are incorporated into persecutory plots. Family members and staff may be misidentified.

Hallucinations are also common. Visual hallucinations are most characteristic, and range in complexity from simple shapes and patterns to fully formed objects, animals, mythological or ghostlike apparitions, and panoramic scenes. They are often brightly coloured, with elements that change in position, size, and number. The hallucinated material may be grossly distorted, as for example in Lilliputian hallucinations, where minute people or objects appear. Combined auditory and visual hallucinations are also frequent. Tactile hallucinations take the form of crawling, creeping, or burning sensations. Delusions of infestation or sexual interference may accompany such sensations. Olfactory hallucinations are also described. In general, hallucinations occur in patients with the hyperalert (see ‘Psychomotor behaviour, emotion, and mood’) variant of delirium. Withdrawal from alcohol and sedative-hypnotics seems particularly prone to produce frank hallucinations.

The sleep–wake cycle

A disruption of the normal circadian sleep–wake cycle is a consistent feature of delirium, and is considered by some authors to be central to the pathogenesis of the syndrome. Insomnia, with a worsening of confusion at night, is common. Other features include daytime sleepiness, dreamlike states with vivid imagery, and a breakdown in the ability to distinguish between dreams and reality.

Electroencephalogram (EEG) tracings taken during the day show fluctuations, and transition from wakefulness, light, rapid eye movement (REM), and deep sleep. Night-time recordings show a loss of the normal orderly progression of the stages of sleep. Maintenance of the normal sleep–wake cycle depends upon the complex interaction of neurotransmitter systems that constitute the reticular activating system (see ‘Applied anatomy’ in the ‘Arousal and Attention’ section in Chapter 1).

Psychomotor behaviour, emotion, and mood

A disturbance of general psychomotor activity is virtually always present in delirium. Two contrasting patterns may be distinguished, but not infrequently patients alternate between the two.

In the hyperalert variant, the patient is restless, excitable, and vigilant. He or she responds promptly, and often excessively, to any stimulus. Speech is voluble and pressured. Shouting, laughing, and crying are common. There is increased physical activity often with repetitive purposeless behaviour, such as groping or picking. Often the patient tries to get out of bed, and attempts at restraint may produce violent outbursts. Autonomic signs of hyperarousal, such as tachycardia, sweating, and pupillary dilatation can be observed. Vivid hallucinations tend to be seen most often in patients with this variant.

Patients with the hypoalert variant are, by contrast, quiet and motionless; they drift off to sleep if stimulated, and display reduced psychomotor activity. Speech is typically sparse and slow; answers to questions are stereotypic, and often incoherent. Despite outward appearances the patient may be experiencing delusions and hallucinations, although they are less frequent than in the hyperalert variant.

Emotional disturbances are very frequent, and may vary from euphoria to depression. A state of perplexity, with apathy and indifference, is perhaps most often seen. Lability is common, and the patient may suddenly become fearful, angry, and aggressive.

Clouding of consciousness

This term was traditionally included in descriptions of delirium, but has been dropped from current definitions. There is no generally accepted definition of consciousness, and ‘clouding’ is an even vaguer term. Consciousness may be considered in a narrow sense to mean a level of wakefulness and response to gross external stimuli. Although patients with delirium may be drowsy and show reduced responses when stimulated, often they are fully awake, and may even be hyperalert. In a broader sense, consciousness has been used to describe the capacity to engage in complex and appropriate thought, to fix, sustain, and shift attention, and to judge the passage of time. Impairment or clouding of consciousness, used in this sense, is thus no more than a metaphor referring to the set of cognitive and attentional deficits that constitute the core of the syndrome of delirium.

Causes of delirium

A variety of factors can cause delirium (see Box 2.2).

Epidemiology and predisposing factors

Delirium is very common in medical inpatients, particularly in a geriatric setting, with an estimated prevalence of 10–20%. In surgical patients it might be even higher. There are a number of well-recognized predisposing factors:

Pathogenesis

The diverse aetiologies of delirium converge on a final common pathway, namely disruption of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) or attentional core as described in Chapter 1.

| Box 2.2 Causes of delirium (acute confusional states) |

|

Dementia

The term ‘dementia’ has traditionally been applied to a syndrome of acquired global impairment of intellectual function which is usually progressive, and occurs in a setting of clear consciousness. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, clouding of consciousness was considered a hallmark of delirium, but because of definition problems this term has been removed from more recent criteria. The defining characteristics of delirium are now the disturbed attentional abilities and disordered thinking that are not seen in dementia. The adjective ‘acquired’ is included to distinguish dementia from congenital or early-life intellectual impairment (mental handicap). The main conceptual development in recent years, however, has been to refine the meaning of ‘global impairment of intellectual function’, so that dementing disorders can now be diagnosed earlier, and with greater accuracy. Although a global or diffuse loss of higher cerebral function is the eventual fate of patients with dementia, the majority (if not all) of cases begin with more circumscribed cognitive impairment. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) definition of dementia (which it now refers to as major neurocognitive disorder) requires:

Causes of dementia

Box 2.3 lists the common causes of dementia, including potentially reversible causes.

Cortical versus subcortical dementia

A division of primary degenerative diseases, which has proved theoretically and practically useful, is between those which affect primarily the cerebral cortex and those in which the major pathological impact is on subcortical structures. The reason for the cognitive impairment in the former is obvious. In the subcortical dementias, the major impact is thought to result from a loss of the normal regulatory effect of subcortical structures on the cortex, particularly the prefrontal area. The term subcortical dementia was initially applied to the cognitive syndrome seen in progressive supranuclear palsy and Huntington’s disease, but has been subsequently applied to a range of basal ganglia and white matter diseases (see Table 2.1).

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the prototypical example of a cortical dementia in which disturbances of memory, language, and visuospatial abilities predominate (see Table 2.2). Attention and frontal executive functions are relatively well preserved in the early stages. The slowing of cognitive processes (bradyphrenia), change in personality, and mood disturbances which characterize subcortical dementias are less prominent until late in the disease. Marked impairment in episodic memory is practically always the earliest feature in AD. The amnesia reflects a failure of encoding and a very rapid forgetting of any new material. Recall and recognition are both severely affected. Remote memory is also affected, with a temporal gradient, in that early-life memories are relatively spared. Within the domain of language, aphasia occurs fairly early in the course: reflecting a breakdown in the semantic components of language, with relative sparing of phonology and syntax; word-finding difficulty in spontaneous conversation, impaired naming on formal tests, and impaired generation of exemplars on category fluency testing (for example, on animals, or fruit) are consistent early findings; the picture in more advanced AD has been likened to transcortical sensory aphasia (see ‘Transcortical sensory aphasia’ in the ‘Language’ section in Chapter 3).

Table 2.1 Cortical and subcortical dementias

| Cortical dementias | Subcortical dementias |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | Progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele–Richardson–Olszewski syndrome) |

| Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease | Huntington’s disease |

| Parkinson’s disease | Wilson’s disease |

| Frontotemporal dementia | Normal pressure hydrocephalus |

| White matter diseases (leucodystrophies and multiple sclerosis | |

| AiDs encephalopathy |

Table 2.2 Summary of features of cortical and subcortical dementias

| Function | Cortical dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease) | Subcortical dementia (e.g. Huntington’s disease) |

|---|---|---|

| Alertness | Normal | Marked ‘slowing up’ (bradyphrenia) |

| Attention | Intact in early stages | Impaired |

| Episodic memory | Severe amnesia | Forgetfulness due to poor encoding; recognition better than recall |

| Frontal ‘executive’ | Normal until late function | Typically impaired from onset |

| Personality | Preserved | Apathetic, inert |

| Language | Aphasic features | Normal, except for reduced output and dysarthria |

| Praxis | Impaired | Normal |

| Visuospatial and perceptual abilities | Impaired | Impaired |

In subcortical dementia, as exemplified by Huntington’s disease or progressive supranuclear palsy, impairment in attentional control and frontal ‘executive’ functions predominates (see Table 2.2). Patients appear characteristically ‘slowed up’ (bradyphrenic), with a marked deficit in the retrieval of information. Spontaneous speech is reduced, and answers to questions are slow and laconic. Changes in mood, personality, and social conduct are very common. Patients are often inert, indifferent, and uninterested. Memory is impaired, mainly as a result of reduced attention leading to poor encoding of new material, but the severe amnesia which typifies AD is not seen in the early stages. Recognition is typically much better than spontaneous recall. It is easy to overestimate the degree of cognitive impairment in patients with subcortical dementia, and performance usually improves with persistence and encouragement. Features of focal cortical dysfunction, such as aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia, are characteristically absent, at least in the earlier stages. But visuospatial and perceptual abnormalities can be demonstrated fairly consistently.

It should be pointed out that not all dementias can be fitted neatly into this dichotomy. In vascular dementia, for example, subcortical features predominate, owing to multiple lacunar lesions in the basal ganglia or diffuse white matter pathology, but there is often evidence of focal cortical damage.

Another recently identified disease in which a mixture of cortical and subcortical features occurs is dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). The pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease is the presence of Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra. In DLB, these inclusion bodies are found throughout the cortex. Patients display a variety of symptoms with characteristic subcortical deficits (particularly poor executive ability and attention), and features of cortical dysfunction, the latter implicating parieto-occipital regions.

Frontotemporal dementia also presents a problem as patients with the behavioural form present with changes in personality and social conduct and classic cortical features.

Alzheimer’s disease

In 1906, Alois Alzheimer reported the case of a woman aged 51 years, Auguste D, with severe amnesia, aphasia, and hallucinations who, at postmortem, showed silver-staining plaques and tangles. For the next 50 years it was considered to be a rare cause of presenile dementia but it gradually became clear that identical pathology was responsible for the majority of cases of late-onset dementia as well. The prevalence rises considerably with advancing age, doubling every 5 years. The distinction between presenile and senile dementia is, in general, no longer valid except that a proportion of young-onset patients have genetic mutations: most commonly involving the presenilin 1 (PSEN1) gene but occasionally the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene. Some PSEN1 mutations are associated with spastic paraparesis. Controversy exists on whether there are other clinical hallmarks of familial AD. It is generally held that young-onset cases have a more rapid progression and may more often present in an atypical fashion with prominent language or frontal features. It should be noted, in passing, that even in early-onset cases only a minority are found to have a gene mutation although the proportion increases considerably in patients with a strong family history of early-onset dementia.

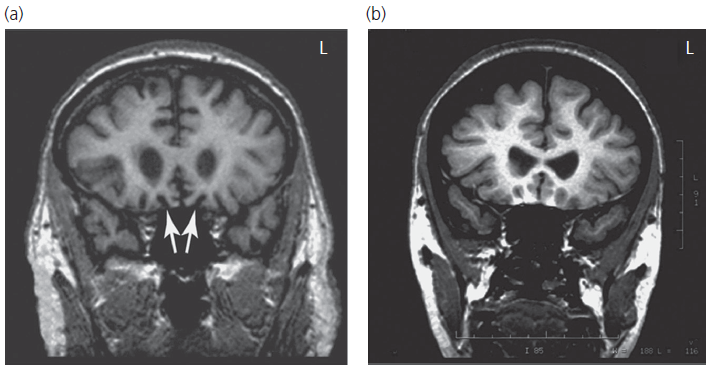

The defining characteristic of AD remains the neuropathology, which consists of intraneuronal tangles of paired helical filaments (PHFs) and extraneuronal plaques containing an amyloid core. PHFs are regarded as more important for the genesis of symptoms and arise initially in the parahippocampal region (specifically the entorhinal cortex) before spreading to the hippocampus proper and the posterior association cortices. The retrosplenial cortex is another site of predilection for early-stage pathology. The staging of pathological changes proposed by Braak and Braak (see Fig. 2.1) has formed the basis of our understanding of the evolution of the cognitive deficits seen in AD.

Fig. 2.1 (a) Braak and Braak stages: cartoon of tangle spread. (b) Brain slice: thin slice of brain through the temporal lobes showing staining with silver, indicating the density of Alzheimer pathology in the medial temporal lobe.

Since there is no definitive way of establishing the diagnosis in life, it has become common practice to apply the term ‘dementia of Alzheimer type’ (DAT). However, with the use of strict research criteria (such as the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS)– Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA) criteria), an accurate diagnosis can be made in at least 80% of cases. AD does not begin with a ‘global’ loss of intellectual function, but generally progresses in a predictable fashion through the following stages.

Stage 1: mild cognitive impairment

From the onset, there is typically severe episodic memory impairment, with features similar to those resulting from other causes of the amnesic syndrome (see ‘The amnesic syndrome: defining characteristics’ in the ‘Memory’ section in Chapter 1). Anterograde amnesia results from poor encoding and rapid forgetting of new material. Retrieval may also be poor with some improvement on cueing or on recognition-based tests. The amnesia is typically global, affecting verbal and non-verbal (faces and shapes etc.) material, but patients with more selective deficits are seen. Tests of associative learning, such as the Paired Associate Learning (PAL) test from the CANTAB battery, appear particularly sensitive. The retrograde memory loss has a temporally graded pattern, with sparing of more distant memories. Short-term (working) memory as judged by digit span is generally normal. Patients are often well oriented at this stage. Language is typically normal on informal assessment, but poor generation of exemplars on category fluency (for example, in naming animals, fruit, etc.) may be found: a dissociation between category fluency (impaired) and letter fluency (preserved) is highly suggestive of AD or semantic dementia. Visuospatial functioning is good. Patients perform normally on simple executive tests but more complex tasks may reveal deficits. Slowing on timed tasks (such as Trails B or digit–symbol substitution) is present in a proportion of cases from an early stage. Social rapport and personality are well preserved, thus often masking the severity of the amnestic problem. Apathy and irritability are the commonest neurobehavioural symptoms and can be found in a fairly high proportion of cases. Many patients suffer from low mood which can be interpreted either in terms of a psychological reaction or a disturbance of neurochemical systems.

Patients typically score above the accepted cut-off on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and continue to perform basic activities of daily living normally. They cannot, therefore, be regarded as ‘demented’ in the classic sense. A number of different labels have been applied to patients in this amnestic prodrome of dementia proper, the accepted one now is mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with recognition of several variants of MCI including amnestic and multi-domain MCI, both of which are strongly associated with subsequent dementia of Alzheimer’s type, as well as a non-amnestic form of MCI, the aetiology of which is much more variable. The prognosis for patients with MCI varies depending on the criteria used in different studies, but a generally agreed figure for conversion to frank dementia is in the order of 10–20% per year. Whether all such patients eventually convert remains a contentious issue but certainly the majority will do so within 5 years of follow-up. We have followed patients for 8 years before conversion to dementia. Current research criteria for amnestic MCI are as shown in Box 2.4.

Stage 2: mild-to-moderate dementia

Worsening memory abilities and impaired attention result in marked temporal disorientation and patients retain very little new information. Remote memory is impaired and deficits in short-term (working) memory are found. Distractibility, poor attention, and problems with frontal executive function are ubiquitous. Breakdown of semantic memory results in diminished vocabulary, word-finding difficulty, and semantic paraphasic errors in spontaneous conversation, very poor naming ability, reduced generation of exemplars on category fluency testing, and a loss of general knowledge. Difficulties with comprehension of syntactically complex sentences and in performing phonological tasks also occur. Visuospatial deficits are readily apparent. Relatives report a general slowing or ageing with difficulty performing everyday activities. Neuropsychiatric symptoms are increasingly prominent with apathy, mood disturbance, irritability and agitation, delusions, and sometimes hallucinations. Social rapport is still partly preserved, thus patients appear (superficially) to be reasonably intact; but beneath the social veneer they are empty shells.

| Box 2.4 Criteria for amnestic mild cognitive impairment |

|

Stage 3: advanced dementia

There is marked global loss in all areas of intellectual function—amnesia, aphasia, agnosia, and so on—and also progressive disintegration of personality. Incontinence, disorders of social conduct, and aggressive behaviour are common. Increasing dependence leads to death.

Atypical Alzheimer’s disease

Although the majority of patients present with episodic memory loss as their most prominent deficit, it is clear that there are two major variants: progressive aphasia and progressive visuospatial impairment. In patients with the former, the pattern is somewhat variable and occasional cases with both semantic dementia and with classic progressive non-fluent aphasia may turn out to have Alzheimer’s pathology, but in recent years it has been proposed that most patients with aphasia in the context of AD have what has been called logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA). Patients with LPA have speech hesitancy and pauses due to word-finding problems and may show phonological errors but, unlike patients with true non-fluent progressive aphasia due to non-AD pathology, they lack apraxia of speech and do not exhibit agrammatism. They are quite severely anomic but, unlike semantic dementia, knowledge of word meaning is intact and an additional characteristic feature is a marked reduction in span with difficulty repeating sentences or strings of words. Note that in aphasic patients it is very difficult to assess episodic memory, so reliance must be placed upon non-verbal tasks such as recall of abstract shapes, recognition of faces, and spatial learning.

Patients with the visual variant of AD, often referred to as posterior cortical atrophy, present with difficulty navigating in unfamiliar environments, problems reaching and grasping objects, various complex visual symptoms including neglect and, on examination, features of Balint’s syndrome are present (see ‘Balint’s syndrome’ in the ‘Achromatopsia, Colour Agnosia, and Colour Anomia’ section in Chapter 3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans in such patients reveal occipitoparietal atrophy. Memory, language, and insight are often very well preserved. As this disorder progresses, patients may become functionally blind. Apraxia is also common. The differentiation of posterior cortical atrophy from corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and DLB can be very difficult.

A third atypical presentation is with predominant frontal pathology. Such patients have dysexecutive and attentional problems, often accompanied by apathy, but in the absence of severe amnesia. Whether such cases ever mimic the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) with changes in social cognition, inhibitory control, empathy, and emotional regulation is more controversial. We have seen the occasional patient with typical bvFTD who has proven Alzheimer’s pathology but such cases are very rare.

Neuroimaging in Alzheimer’s disease

The most important role of imaging in patients with suspected AD is to exclude other potentially treatable disorders (see later in chapter). Computed tomography (CT) scanning is generally unremarkable in the early stages. Even standard clinical MRI scans may be passed as normal. Research MRI with coronal cuts will show hippocampal atrophy from an early stage although these changes are subtle and hard to detect unless volumetric analyses are used. Functional scans (single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET)) reveal more striking changes with posterior cingulate or bilateral parieto-temporal hypometabolism, or both. The most recent innovation in PET imaging is the use of amyloid labelling ligands, notably Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), which bind avidly to intracerebral amyloid even in those with MCI, although a proportion of apparently normal older controls also show positive uptake of the tracer.

Frontotemporal dementia

Arnold Pick, a contemporary of Alois Alzheimer, recognized in the early years of the twentieth century the existence of patients with both progressive fluent aphasia and personality deterioration associated with focal atrophy confined, at least initially, to either the frontal or temporal lobes. This is now referred to as frontotemporal dementia (FTD), or sometimes frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). Characteristic pathological changes, distinct from that seen in AD—silver-positive (argyrophilic) inclusions known as Pick bodies— were subsequently identified, although it was later found that these histological changes are present in a minority of cases.

The past decade has seen an explosion of knowledge concerning the pathology and genetics of FTD. Four major pathological subforms are now recognized:

A high proportion of younger-onset dementia cases, seen in specialist clinics, have FTD. Two recent UK-based epidemiological studies have shown that, under the age of 65 years, FTD is almost as common as AD. Up to a third of patients have a positive family history using the broad inclusion criteria of a relative with dementia, Parkinson’s disease, or MND. Patients from an established kindred with more than one first-degree relative affected are rarer. Most familial cases have a mutation of one of three genes: the MAPT gene or GRN gene, both of which are on chromosome 17, or the C9orf72 gene, which was the most recently identified gene mutation, a unique hexanucleotide repeat expansion on chromosome 9, associated with familial FTD or MND, or both, and also found in a small proportion of apparently sporadic bvFTD cases.

There is growing awareness of the overlap between FTD and both MND and corticobasal syndrome (CBS): around 10% of patients with FTD develop clinically overt MND, usually of the bulbar type. These patients typically have rapidly progressive FTD with prominent behavioural changes as well as aphasia and sometimes psychotic phenomena. Within 12 months they develop features of MND. Conversely, a similar proportion of patients with MND also develop overt FTD but a much higher proportion show more subtle behavioural changes, notably apathy and sometimes disinhibition and stereotypical behaviours.

Although CBS was initially characterized by asymmetric parkinsonism with severe limb apraxia, alien limb phenomena, falls, and myoclonus, it is now clear that many (if not all) patients develop cognitive deficits, usually characterized by a progressive non-fluent aphasia with marked word finding and phonological deficits together with frontal executive problems reflecting involvement of the parietal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices. Visuospatial impairment is also common in CBS, unlike the other FTD syndromes.

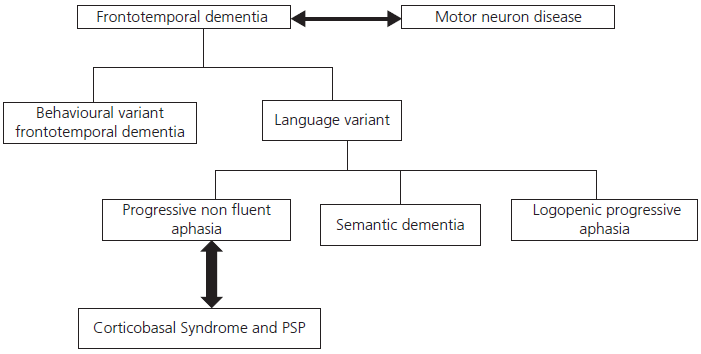

The relationship between FTD syndromes, MND, and CBD is illustrated in Fig. 2.2.

Behavioural (frontal) presentation

This is the commonest variant of FTD and presents with changes in personality and social conduct (see Box 2.5). Patients become unconcerned, lacking in initiative, motivation, judgement, and forethought, and neglect their personal responsibilities, leading to mismanagement of domestic and financial affairs. Medical referral may occur following demotion, dismissal from work, or increasing marital disharmony. Patients are typically unaware of these changes. A common early symptom is a lack of understanding of social conventions with reduced courtesy. Social faux pas become gradually more glaring. An indifference to the feelings of others with impaired empathy and sympathy is very common.

Increasing inflexibility and adoption of fixed daily routines is very common. Activities often acquire a marked stereotypic quality. Patients may clock-watch, carrying out a particular activity at precisely the same time every day. Wandering may involve completion of an identical route at exactly the same time every day. Some patients constantly repeat the same phrase or sentence.

Changes in eating are very common. Overeating and especially a craving for sweet foods may lead relatives to ration food. Food fads are common, involving sweet, and highly flavoured, foods. Excessive and indiscriminate eating leads to obesity. Altered sexual behaviour is common which may take the form of loss of libido. Conversely, some patients may make inappropriate sexual advances.

Fig. 2.2 Relationship between frontotemporal dementia, motor neuron disease, and corticobasal degeneration.

| Box 2.5 Key behavioural characteristics of frontotemporal dementia |

|

Problems with planning, organizing, and goal setting are typical and contribute to failure in complex situations such as the workplace. Patients may show apathy, inertia, and aspontaneity or alternatively can be overactive, restless, distractible, and disinhibited. Often patients alternate from one to the other, dependent on the environmental situation.

As the disease progresses, patients typically neglect personal hygiene and need to be encouraged to change their clothes and to wash.

Establishing a definitive diagnosis can be very difficult as patients can appear normal and perform well on standard screening cognitive instruments such as the MMSE. Even frontal executive tests may fail to reveal deficits, as such tests rely more upon dorsolateral prefrontal cortical regions whereas the pathology in FTD involves the orbitomesial frontal cortex. More recently devised tests of decision-making and complex planning may be more sensitive. Tasks designed to evaluate ‘theory of mind’ (see discussion in ‘Motivation, inhibitory control, and social cognition’ in the ‘Higher-Order Cognitive Function, Personality, and Behaviour’ section in Chapter 1) and emotion recognition reveal marked problems but remain research-based tools at present.

The realization that psychiatric disorders may mimic bvFTD and that not all cases with carer reports of symptoms of bvFTD progress over time has led to a revision of the criteria for bvFTD by an international group of experts with a proposal of three levels of diagnosis: possible, probable, and definite as shown in Box 2.6.

CT scans are frequently normal in such patients and standard MRIs may be reported as normal. On good-quality coronal MRI images, most patients show atrophy of the orbital or mesial frontal regions and volumetric methods of analysis show atrophy of these regions and the insular cortex in the early stages (see Fig. 2.3). Functional brain imaging, if available, using SPECT or PET is significantly more sensitive and will usually show frontal hypometabolism (Box 2.6).

Primary progressive aphasia

The term primary progressive aphasia (PPA) was introduced in the 1980s to describe patients presenting with a disorder of communication in the absence of other significant cognitive deficits which gradually worsens. Gradually it was realized that the pathological basis of this disorder was the same as that found in bvFTD and indeed many cases with PPA went on to develop the behavioural symptoms that typify bvFTD. Two forms of PPA were recognized. The fluent variant is more often called semantic dementia because of the underlying core breakdown in semantic memory that is associated with consistent neuroimaging changes and underlying pathology (see following ‘Semantic dementia’ section). The other non-fluent variant was recognized to be far more variable and with a range of underlying pathologies including AD. A major development has been a subdivision of non-fluent PPA into a true agrammatic form of non-fluent PPA (usually secondary to non-Alzheimer’s forms of tauopathy) and a so-called logopenic variant which is typically associated with Alzheimer’s pathology. An international group has now proposed criteria for the diagnosis of each of these three variants of PPA.

Fig. 2.3 Coronal magnetic resonance images showing selective atrophy of the orbital frontal cortex in a patient with early-stage behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia.

| Box 2.6 Criteria of possible, probable and definite behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia |

|

Possible bvFTD. Three of the flowing A–F must be present:

Probable bvFTD. All of the following must be present:

Definite bvFTD:

|

Semantic dementia

The commonest presentation of this variant of PPA is ‘loss of memory for words’ and a shrinking vocabulary. Anomia is a salient and very early feature both in spontaneous speech and on confrontational testing. The use of terms such as ‘thing’ is common and semantically related word substitutions or circumlocutions may occur. Patients often adopt a relatively complex word or phrase which is used repeatedly, such as ‘situation or special place’. The degree of comprehension impairment is often masked in conversation due to the clues from context, apparent in phrases such as ‘How did you get to the hospital today?’ Comprehension of single words, whether written or spoken, is, however, impaired. The feeling of familiarity may remain when the information associated with words has been lost. For instance, when asked the meaning of the word ‘hobby’, patients often say ‘Hobby, hobby, I’m sure, I should know what that means but I can’t remember’; this contrasts with their striking preservation of syntax and phonology. Their difficulty defining the meaning of words initially affects relatively low-familiarity items such as ‘harmony, theft, caterpillar, penguin, and accordion’. In contrast to AD, semantic dementia patients show good autobiographical memory for personally experienced events which occurred in the past few years and remain well orientated and attentive. Route-finding skills and topographical memory are also good.

Category fluency is a sensitive way of detecting semantic deficits with a reduction in the number of examples of animals that can be named. This is even more striking when subjects are asked to name birds or breeds of dog. Repetition is intact, such that patients can repeat multisyllabic words like ‘hippopotamus’ and ‘encyclopaedia’ but have no idea of their meaning. Surface dyslexia and surface dysgraphia are typical accompaniments of semantic dementia (see ‘Surface dyslexia’ in the ‘Disorders of Reading: The Dyslexias’ section in Chapter 3).

The breakdown in semantic knowledge is most easily demonstrated using verbally based tests but non-verbal tests of associative knowledge (such as the Pyramids and Palm Trees Test) or tasks involving matching sounds to pictures, or colouring objects reveal deficits at a very early stage of the disease. The fact that there is breakdown of a central semantic knowledge base has led most authorities to prefer the term semantic dementia rather than progressive fluent aphasia to describe such patients.

In addition to the preservation of episodic memory, visuospatial attentional and executive abilities are usually preserved in the early stages which contrast sharply with the typical features of AD discussed earlier in this chapter.

It has become increasingly apparent that many patients with semantic dementia undergo the changes in behaviour similar to those seen in the frontal variant of FTD. Ritualized and obsessive interests such as jigsaws and word searches, alterations in food preference, loss of empathy, and emotional coldness are particularly common. As the disease progresses, patients may develop Klüver–Bucy syndrome as a result of bilateral damage to the anterior temporal lobe. The features of this syndrome are a tendency to consume inedible things and to put objects in the mouth (hyperorality) and marked alterations in sexual behaviour.

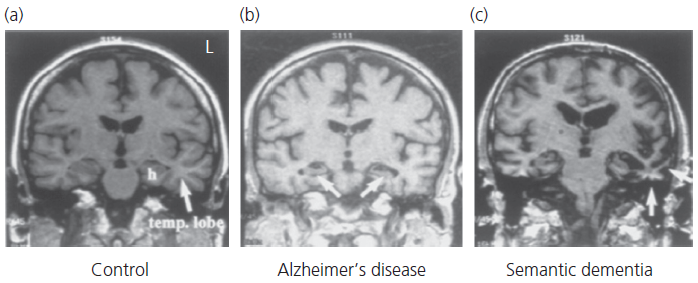

Structural brain imaging (MRI) in patients with semantic dementia reveals atrophy of the polar and inferior temporal regions; the parahippocampal and fusiform gyri are typically affected to the greatest extent with marked asymmetry—the left being worse than the right—sometimes strikingly so (see Fig. 2.4). Coronal images are needed to detect these changes in the early stages and CT scans may appear normal due to the angle of acquisition through the temporal lobes. Changes on fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET parallel those seen on MRI with selective hypoperfusion of the anterior temporal lobes(s).

Fig. 2.4 Coronal magnetic resonance images in typical cases of Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia in contrast to a normal age-matched control.

Over the past decade, an increasing number of cases with the much less common pattern of right predominant atrophy have been reported. These patients present with a form of progressive prosopagnosia which, unlike the modality (face)-specific form seen after right occipitotemporal strokes, affects the ability to recognize and identify people regardless of the modality of input (face, name, and voice). As in the more typical left predominant semantic dementia cases, there is a familiarity effect in that less familiar people (Sean Connery, Gary Lineker) are ‘lost’ before highly familiar (David Cameron, David Beckham) famous people and family members. Changes in personality are also prominent with the development of coldness and indifference.

The underlying pathology in semantic dementia is very consistently an accumulation of TDP43-positive inclusions with a very characteristic pattern of staining, although very occasional cases may have tau-positive FTD.

Progressive non-fluent aphasia

In contrast to semantic dementia, there is profound disruption of speech output with speech-based errors or agrammatism, or both. Speech may be hesitant and distorted with groping for words and loss of prosody (known as apraxia of speech). Alternatively, the main deficit may be in the grammatical aspects of speech with a simplification or frank grammatical errors with a marked reduction in output. The language syndrome resembles Broca’s aphasia in the context of inferior frontal and insula damage. Comprehension of word meaning is preserved and patients perform normally on conceptual and associative tasks such as the Pyramids and Palm Trees Test. Patients often show deficits on tests of syntactic comprehension. The anomia is less profound than in semantic dementia but, in common with this syndrome, there is a marked reduction in fluency affecting both letter- and category-based fluency. Patients have great difficulty repeating multisyllabic words and phrases but retain meaning and hence show the opposite pathology to that seen in semantic dementia.

In common with semantic dementia, episodic memory and visuospatial function are well preserved; however, executive deficits are quite common. Behavioural changes seem relatively rare in the early stages. As the disease evolves, orobuccal or limb apraxia commonly develops and there is increasing awareness of the overlap between progressive non-fluent aphasia and CBS.

Imaging studies in non-fluent PPA show left hemisphere atrophy particularly involving the anterior insula. These changes are easily missed on MRI even with good-quality coronal images. Functional scans (SPECT or FDG-PET) show more extensive areas of hypometabolism involving the left frontal area.

The pathology in non-fluent PPA is more variable than that seen in semantic dementia. Patients with predominant apraxia of speech appear to have tau-positive FTD while the more agrammatic cases may have FTD-tau or FTD-TDP43.

Logopenic progressive aphasia

This third variant of PPA is the most recently defined and remains somewhat controversial. Some authorities argue that, unlike the other variants of PPA, there is little coherence and consistency to the syndrome while others believe that cases of LPA can be identified and that it is useful as the majority of such patients have AD as the underlying pathological substrate.

Patients present with anomia causing pauses and hesitation to conversation but unlike those with non-fluent PPA they lack agrammatism and do not display features of speech apraxia. They may, however, produce phonological errors in which one whole speech sound replaces another (sluper for supper, hargo for cargo, head for bread, etc.) and these can be difficult to distinguish from motor speech errors in which there is distortion of speech sounds. Naming is usually markedly impaired but unlike in semantic dementia, word comprehension is preserved. A reduction in span is characteristic, causing problems repeating phrases, sentences, and list of words. Patients may fail on tests of syntactic comprehension since such tasks typically require comprehension of quite long sentences which patients with LPA are unable to retain.

On brain imaging, there is atrophy of the left posterior peri-Sylvian region involving the angular gyrus and superior temporal lobe although this can be difficult to see without coronal MRI images. Function imaging (SPECT or FDG-PET) reveals more extensive hypometabolism of the left parietal and temporal lobes. In this syndrome, unlike the other PPA variants, amyloid-based PET imaging is almost always positive in keeping with limited pathological series which have shown consistent underlying Alzheimer’s pathology.

Vascular dementia

This term has replaced the older label ‘multi-infarct dementia’ with the realization that only a proportion of patients with cognitive impairment in the context of cerebrovascular disease have classic multi-infarct disease (MID). Patients with MID typically present following a recent large vessel or lacunar stroke, or both, in the context of thromboembolism from extracranial arteries or small-vessel disease in the brain. Vascular risk factors, especially hypertension, are readily apparent, and many patients have other evidence of atheromatous vascular disease (angina, claudication, cervical bruits, etc.). There may be a stepwise progression, with periods of deterioration followed by more stable periods. Cognitively, impaired attention and frontal features predominate, owing to a concentration of small vascular lesions (lacunes) in the basal ganglia and thalamic regions; but features of cortical dysfunction are also frequently present. Fluctuations in performance and night-time confusion are very common. Emotional lability, pseudobulbar palsy, gait disturbance, and incontinence are characteristic.

The majority of cases with vascular dementia do not have typical MID but instead present with more insidious decline largely indistinguishable from AD in the context of chronic vascular risk factors with, or without, periods of confusion. Imaging by MRI reveals diffuse and often confluent white matter pathology involving the periventricular zone and deep white matter (leucoaraiosis) as a consequence of occlusion of deep penetrating blood vessels. In contrast to AD, the episodic memory deficit is less dense and involves recall more than retrieval. Patients are slowed up and show gross deficits on executive tasks that require mental flexibility, shifting, and response inhibition (such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and the Stroop Test). Impairments in visuospatial and perceptual abilities may be prominent. The majority are apathetic with limited insight.

A diagnosis of vascular dementia should lead to a search for underlying aetiologies including cardiac emboli, thromboembolic atherosclerotic large-vessel disease, vasculitides, prothrombotic states, notably the antiphospholipid syndrome, and, in younger patients with a positive family history of genetic disorders, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leucoencephalopathy (CADSIL) or the mitochondrial cytopathies.

Huntington’s disease

This genetic disorder is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and has a negligible new mutation rate. Patients have mutations of the huntingtin (HTT) gene on chromosome 3 due to an excess of CAG repeats. The size of the mutation defines the age of onset. Most, but not all, cases occur in the context of a known family history. In apparently de novo cases, it is necessary to question several family members to search for clues, such as a family history of psychiatric illness, suicide, dementia, or movement disorders.

Huntington’s disease may present with psychiatric, neuropsychological, or neurological symptoms. The peak age of presentation is in the 40s, but the age of presentation can be as late as 70 years. Depression is common, but a schizophrenic-like state with paranoid delusions may also occur. An insidious change in personality, with the development of sociopathic behaviour, is very characteristic. Suicide is a frequent cause of death. The neuropsychological picture is one of subcortical dementia, with marked impairment on tests of attention and frontal function. Patients are forgetful because of impaired attention, but do not show marked amnesia. Language is preserved until late in the course. Visuoperceptual deficits also occur fairly consistently.

The earliest sign of the movement disorder is a restless fidgetiness of the limbs, which the patient may learn to disguise. Eventually the chorea affects the face and extremities. The gait becomes unsteady and reeling. On walking, characteristic finger-flicking movements may be observed.

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Patients with Parkinson’s disease have Lewy bodies (α-synuclein and ubiquitin-positive inclusions) confined to the substantia nigra and causing dopaminergic depletion. In DLB, these inclusions are more widespread and involve cortical regions as well as the substantia nigra. It is now thought that DLB is as common as vascular dementia in the elderly, and second only to AD in terms of neurodegenerative disorders. The clinical features can be considered a hybrid of Parkinson’s disease and AD. Some patients present primarily with parkinsonism often without tremor, others present with progressive cognitive impairment as the prominent feature and develop rigidity or bradyphrenia, or both, later. Spontaneous fluctuations with periods of frank delirium are characteristic, as are unprovoked visual hallucinations consisting often of people, faces, or animals. A history of vivid dreams or even ‘acting out’ of dreams, so-called REM behavioural sleep disorder, is also common and may precede other features by a number of years. Some patients have falls and autonomic dysfunction appears to be common so postural hypotension may confound balance problems to induce gait instability. Mood disturbance is common and the patients are exquisitely sensitive to small doses of neuroleptics which may precipitate the malignant neuroleptic syndrome (coma, catatonia, hyperpyrexia, hypercatabolism, and renal failure).

Cognitively, amnesia is less dense than in AD, but attention and visuospatial/perceptual abilities are typically more impaired. MRI changes in DLB are indistinguishable from AD but SPECT scanning may show disproportionately severe occipital hypoperfusion.

Progressive supranuclear palsy

Previously regarded as a very rare parkinsonian syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy (or Steele–Richardson–Olszewski syndrome) is now known to be a relatively common disorder which often presents with prominent frontal-executive dysfunction or apathy, or both. A reduction of speech output without frank linguistic deficits (so-called dynamic aphasia) is characteristic, often with alterations in speech pitch or clarity. Later, frank bulbar features occur. Falls and postural instability are early motor features. Axial rigidity and paralysis of vertical eye movements are characteristic: patients are unable to initiate saccadic (fast) eye movements and later show poor following movements although oculocephalic reflexes (demonstrated by asking the patient to fixate on an object while moving the head) are intact, giving rise to the term ‘supranuclear’ gaze palsy. The dementia may progresses fairly rapidly.

Pseudodementia

This term has been used to describe two rather distinct clinical syndromes: hysterical pseudodementia and depressive pseudodementia. The latter is more common, and is undoubtedly the most important treatable cause of memory failure.

Patients with hysterical pseudodementia usually present with a fairly abrupt onset of memory and intellectual loss. They typically appear unconcerned. Unlike organic amnesic disorders, the memory impairment is often worse for very salient personal and early-life events. Loss of personal identity may be seen. Memory is strikingly worse when being tested than during informal conversation about recent events. There is usually an identifiable precipitant (such as bereavement, marital problems, or offending) and a past psychiatric history. Patients may show features of the so-called Ganser’s syndrome, the core symptom of which is the giving of ‘approximate answers’. For example, when asked ‘How many legs does a cow have?’, they answer ‘Three’, or in response to ‘What is two plus two?’ they reply ‘Five’. Another classic question is ‘What colour is an orange?’! As in other hysterical conversion states, there may be an underlying organic disorder that has been grossly exaggerated at either a conscious or a subconscious level.

Depressive pseudodementia is, on the whole, a condition of the elderly. Patients present complaining of poor memory or concentration, and deny overt depression. Clues to the diagnosis are biological features of depression, especially disturbed sleeping, low energy, psychomotor retardation, pessimistic and ruminative thoughts, and a lack of interest in activities and hobbies. The onset of the memory failure is usually relatively acute or subacute. A past or family history of affective illness may be an important marker. On bedside cognitive testing, attention is impaired, and performance on memory and executive tasks is patchy and often inconsistent. Typically, digit span and registration of a name and address are poor, but with repeated trials these improve; and the rapid forgetting of information seen in AD is not found. Responses on memory and other cognitive tests are frequently ‘Don’t know’. Language output is often slow and sparse, but paraphasic errors are not seen. Naming may elicit ‘Don’t know’ responses rather than other types of error. In some cases, however, it may be impossible to distinguish true dementia from pseudodementia on simple cognitive tests. If any of the mentioned symptoms or signs are present, a psychiatric opinion and a formal neuropsychological evaluation must be sought.

Rapidly progressive dementia

In patients with a history of relatively abrupt onset and progression, the differential diagnosis is different to that of typical insidiously progressive dementia. Such patients require intensive investigation to exclude the causes listed in Table 2.3.

Imaging in the dementias

The goals of imaging are:

After the introduction of CT scanning, a number of studies were undertaken which attempted to develop criteria for imaging with the primary aim of detecting potentially reversible causes and structural causes (tumours, subdural and normal pressure hydrocephalus). A summary of the most robust criteria is shown in Box 2.7. Patients with any of these features should be scanned. In old-age psychiatric or geriatric practice between 1% and 8% of patients are said to have a potentially reversible cause and about 80% of these will be detected by the strict application of these criteria. Many clinicians would regard this as an unacceptably low rate of detection and would therefore advocate imaging with CT or MRI for all patients with dementia.

Table 2.3 Causes of a rapidly progressive dementing illness

| Inflammatory | Cerebral vasculitis |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Neoplastic | Primary central nervous system tumour |

| Cerebral metastases | |

| Paraneoplastic (limbic encephalitis) | |

| Autoimmune | Voltage-gated potassium antibody syndrome |

| Nutritional | Thiamine deficiency (Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome) |

| Infectious | Cerebral abscess |

| Herpes encephalitis | |

| Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | |

| Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis | |

| Whipple’s disease | |

| Prion | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| Vascular | Multiple infarcts (e.g. emboli secondary to endocarditis) |

| CADASIL |

| Box 2.7 Proposed criteria for imaging patients with dementia if resources are limited |

|

Young-onset dementia

Over the age of 65 years, three disorders together account for at least 80% of all cases—AD, DLB, and vascular dementia—while potentially reversible disorders cause, at most, 5%. Under 65 years of age, the situation is quite different. AD is still the commonest single cause (30–40%), with FTD running a close second. Vascular dementia and Huntington’s disease are also relatively common. This leaves, however, a third of cases due to the other causes shown in Box 2.3, some of which are treatable, while many are genetically determined. The basic message is that rare disorders together account for a sizeable proportion of early-onset cases and the younger the patient, the more likely you are to find an unusual disease. All patients aged under 65 years require detailed investigation.

Differential Diagnosis of Delirium and Dementia

See Table 2.4 for the features used in the differential diagnosis of delirium and dementia.

Table 2.4 Differential diagnosis of delirium and dementia

| Feature | Delirium | Dementia |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Acute, often at night | Insidious |

| Course | Fluctuating, with lucid intervals during the day; worse at night | Stable over the course of the day |

| Duration | Hours to weeks | Months or years |

| Awareness | Reduced | Clear |

| Alertness | Abnormally low or high | Usually normal |

| Attention | Impaired, causing distractibility; fluctuation over the course of the day | Relatively unaffected; impaired in DLB and vascular dementia |

| Orientation | Usually impaired for time; tendency to mistake unfamiliar places and persons | Impaired in later stages |

| Short-term (working) memory | Always impaired | Normal in early stages |

| Episodic memory | Impaired | Impaired |

| Thinking | Disorganized, delusional | Impoverished |

| Perception | Illusions and hallucinations, usually visual and common | Absent in earlier stages, common later; common in DLB |

| Speech | Incoherent, hesitant, slow, or rapid | Difficulty in finding words |

| Sleep–wake cycle | Always disrupted | Usually normal |

DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies.